Twevolution, the Arab Spring [by Twitter] is universally considered the most important story of the year, much less just in Africa. But I believe the Kenyan invasion of Somalia will have as lasting an effect on Africa, so I’ve considered them both Number One.

Twevolution, the Arab Spring [by Twitter] is universally considered the most important story of the year, much less just in Africa. But I believe the Kenyan invasion of Somalia will have as lasting an effect on Africa, so I’ve considered them both Number One.

1A: KENYA INVADES SOMALIA

On October 18 Kenya invaded Somalia, where 4-5,000 of its troops remain today. Provoked by several kidnapings and other fighting in and around the rapidly growing refugee camp of Dadaab, the impression given at the time was that Kenyans had “just had enough” of al-Shabaab, the al-Qaeda affiliated terrorism group in The Horn which at the time controlled approximately the southern third of Somalia. Later on, however, it became apparent that the invasion had been in the works for some time.

At the beginning of the invasion the Kenyan command announced its objective was the port city of Kismayo. To date that hasn’t happened. Aided by American drones and intelligence, and by French intelligence and naval warships, an assessment was made early on that the battle for Kismayo would be much harder than the Kenyans first assumed, and the strategy was reduced to laying siege.

That continues and remarkably, might be working. Call it what you will, but the Kenyan restraint managed to gain the support of a number of other African nations, and Kenya is now theoretically but a part of the larger African Union peacekeeping force which has been in Somali for 8 years. Moreover, the capital of Mogadishu has been pretty much secured, a task the previous peace keepers had been unable to do for 8 years.

The invasion costs Kenya dearly. The Kenyan shilling has lost about a third of its value, there are food shortages nationwide, about a half dozen terrorist attacks in retribution have occurred killing and wounding scores of people (2 in Nairobi city) and tourism – its principal source of foreign reserves – lingers around a third of what it would otherwise be had there be no invasion.

At first I considered this was just another failed “war against terrorism” albeit in this case the avowed terrorists controlled the country right next door. Moreover, I saw it as basically a proxy war by France and the U.S., which it may indeed be. But the Kenyan military restraint and the near unanimous support for the war at home, as well as the accumulation of individually marginal battle successes and outside support now coming to Kenya in assistance, all makes me wonder if once again Africans have shown us how to do it right.

That’s what makes this such an important story. The possibility that conventional military reaction to guerilla terrorism has learned a way to succeed, essentially displacing the great powers – the U.S. primarily – as the world’s best military strategists. There is as much hope in this statement as evidence, but both exist, and that alone raises this story to the top.

You may also wish to review Top al-Shabaab Leader Killed and Somali Professionals Flee as Refugees.

1B: TWEVOLUTION CHANGES EGYPT

The Egyptian uprising, unlike its Tunisian predecessor, ensured that no African government was immune to revolution, perhaps no government in the world. I called it Twevolution because especially in Egypt the moment-by-moment activities of the mass was definitely managed by Twitter.

And the particular connection to Kenya was fabulous, because the software that powered the Twitter, Facebook and other similar revolution managing tools came originally from Kenya.

Similar of course to Tunisia was the platform for any “software instructions” – the power of the people! And this in the face of the most unimaginable odds if you’re rating the brute physical force of the regime in power.

Egypt fell rather quickly and the aftermath was remarkably peaceful. Compared to the original demonstrations, later civil disobedience whether it was against the Coptics or the military, was actually quite small. So I found it particularly fascinating how world travelers reacted. Whereas tourist murders, kidnapings and muggings were common for the many years that Egypt experienced millions of visitors annually, tourists balked at coming now that such political acts against tourists no longer occurred, because the instigators were now a part of the political process! This despite incredible deals.

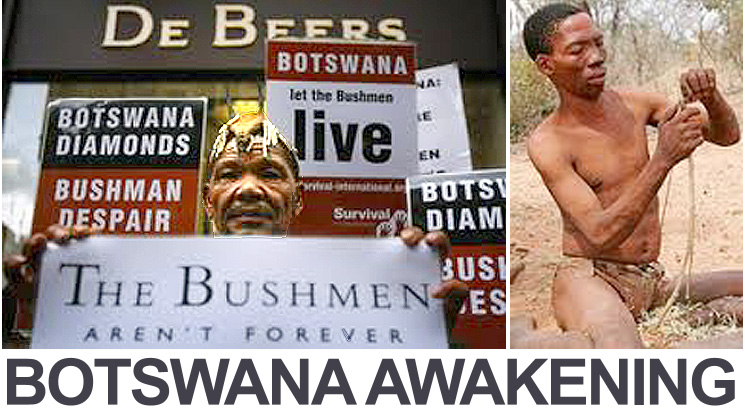

We wait with baited breath for the outcome in Syria, but less visible countries like Botswana and Malawi also experienced their own Twevolution. And I listed 11 dictators that I expected would ultimately fall because of the Egyptian revolution.

Like any major revolution, the path has been bumpy, the future not easily predicted. But I’m certain, for example, that the hard and often brutal tactics of the military who currently assumes the reins of state will ultimately be vindicated. And certainly this tumultuous African revolution if not the outright cause was an important factor in our own protests, like Occupy Wall Street.

3: NEW COUNTRY OF SOUTH SUDAN

The free election and emergence of South Sudan as Africa’s 54th country would have been the year’s top story if all that revolution hadn’t started further north! In the making for more than ten years, a remarkably successful diplomatic coup for the United States, this new western ally rich with natural resources was gingerly excised from of the west’s most notorious foes, The Sudan.

Even as Sudan’s president was being indicted for war crimes in Darfur, he ostensibly participated in the creation of this new entity. But because of the drama up north, the final act of the ultimate referendum in the South which set up the new republic produced no more news noise than a snap of the fingers.

Regrettably, with so much of the world’s attention focused elsewhere, the new country was hassled violently by its former parent to the north. We can only hope that this new country will forge a more humane path than its parent, and my greatest concern for Africa right now is that global attention to reigning in the brutal regime of the north will be directed elsewhere.

4: UGANDA FALTERS

Twevolution essentially effected every country in Africa in some way. Uganda’s strongman, Yoweri Museveni, looked in the early part of the last decade like he was in for life. Much was made about his attachment to American politicians on the right, and this right after he was Bill Clinton’s Africa doll child.

But even before Twevolution – or perhaps because of the same dynamics that first erupted in Tunisia and Egypt – Museveni’s opponents grew bold and his vicious suppression of their attempts to legitimately oust him from power ended with the most flawed election seen in East Africa since Independence.

But unlike in neighboring Kenya where a similar 2007 election caused nationwide turmoil and an ultimate power sharing agreement, Museveni simply jailed anyone who opposed him. At first this seemed to work but several months later the opposition resurfaced and it became apparent that the country was at a crossroads. Submit to the strongman or fight him.

Meanwhile, tourism sunk into near oblivion. And by mid-May I was predicting that Museveni was the new Mugabe and had successfully oppressed his country to his regime. But as it turned out it was a hiatus not a surrender and a month later demonstrations began, twice as strong as before. And it was sad, because they went on and on and on, and hundreds if not thousands of people were injured and jailed.

Finally towards the end of August a major demonstration seemed to alter the balance. And if it did so it was because Museveni simply wouldn’t believe what was happening.

I wish I could tell you the story continued to a happy ending, but it hasn’t, at least not yet. There is an uneasy calm in Ugandan society, one buoyed to some extent by a new voice in legislators that dares to criticize Museveni, that has begun a number of inquiries and with media that has even dared to suggest Museveni will be impeached. The U.S. deployment of 100 green berets in the country enroute the Central African Republic in October essentially seems to have actually raised Museveni’s popularity. So Uganda falters, and how it falls – either way – will dramatically alter the East African landscape for decades.

5: GLOBAL WARMING

This is a global phenomena, of course, but it is the developing world like so much of Africa which suffers the most and is least capable of dealing with it. The year began with incessant reporting by western media of droughts, then floods, in a confused misunderstanding of what global warming means.

It means both, just as in temperate climates it means colder and hotter. With statistics that questions the very name “Developed World,” America is reported to still have a third of its citizens disputing that global warming is even happening, and an even greater percentage who accept it is happening but believe man is not responsible either for it occurring or trying to change it. Even as clear and obvious events happen all around them.

Global warming is pretty simple to understand, so doubters’ only recourse is to make it much more confusing than it really is. And the most important reason that we must get everyone to understand and accept global warming, is we then must accept global responsibilities for doing something about it. I was incensed, for example, about how so much of the media described the droughts in Africa as fate when in fact they are a direct result of the developed world’s high carbon emissions.

And the news continued in a depressing way with the very bad (proponents call it “compromised”) outcome of the Durban climate talks. My take was that even the countries most effected, the developed world, were basically bought off from making a bigger stink.

Environmentalists will argue, understandably, that this is really the biggest story and will remain so until we all fry. The problem is that our lives are measured in the nano seconds of video games, and until we can embrace a long view of humanity and that our most fundamental role is to keep the world alive for those who come after us, it won’t even make the top ten for too much longer.

6: COLTAN WARS IMPEDED

This is a remarkable story that so little attention has been given. An obscure part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act essentially halved if not ultimately will end the wars in the eastern Congo which have been going on for decades.

These wars are very much like the fractional wars in Somalia before al-Shabaab began to consolidate its power, there. Numerous militias, certain ones predominant, but a series of fiefdoms up and down the eastern Congo. You can’t survive in this deepest jungle of interior Africa without money, and that money came from the sale of this area’s rich rare earth metals.

Tantalum, coltran more commonly said, is needed by virtually every cell phone, computer and communication device used today. And there are mines in the U.S. and Australia and elsewhere, but the deal came from the warlords in the eastern Congo. And Playbox masters, Sony, and computer wizards, Intel, bought illegally from these warlords because the price was right.

And that price funded guns, rape, pillaging and the destruction of the jungle. The Consumer Protection Agency, set up by the Dodd-Frank Act, now forbids these giants of technology from doing business in the U.S. unless they can prove they aren’t buying Coltran from the warlords. Done. War if not right now, soon over.

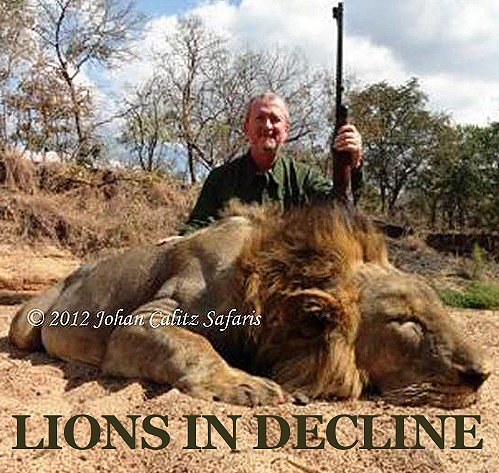

7: ELEPHANTS AND CITES

The semi-decade meeting of CITES occurred this March in Doha, Qatar, and the big fight of interest to me was over elephants. The two basic opposing positions on whether to downlist elephants from an endangered species hasn’t changed: those opposed to taking elephants off the list so that their body parts (ivory) could be traded believed that poaching was at bay, and that at least it was at bay in their country. South Africa has led this flank for years and has a compelling argument, since poaching of elephants is controlled in the south and the stockpiling of ivory, incapable of being sold, lessens the funds that might otherwise be available for wider conservation.

The east and most western countries like the U.S. and U.K. argue that while this may be true in the south, it isn’t at all true elsewhere on the continent, and that once a market is legal no matter from where, poaching will increase geometrically especially in the east where it is more difficult to control. I concur with this argument, although it is weakened by the fact that elephants are overpopulated in the east, now, and that there are no good strategic plans to do something about the increasing human/elephant conflicts, there.

But while the arguments didn’t change, the proponents themselves did. In a dramatic retreat from its East African colleagues, Tanzania sided with the south, and that put enormous strain on the negotiations. When evidence emerged that Tanzania was about the worst country in all of Africa to manage its poaching and that officials there were likely involved, the tide returned to normal and the convention voted to continue keeping elephants listed as an endangered species.

8: RHINO POACHING REACHES EXTREME LEVELS

For the first time in history, an animal product (ground rhino horn) became more expensive on illicit markets than gold.

Rhino, unlike elephant, is not doing well in the wild. It’s doing wonderfully in captivity and right next to the wild in many private reserves, but in the wild it’s too easy a take. This year’s elevation of the value of rhino horn resulted in unexpectedly high poaching, and some of it very high profile.

9: SERENGETI HIGHWAY STOPPED

This story isn’t all good, but mostly, because the Serengeti Highway project was shelved and that’s the important part. And to be sure, the success of stopping this untenable project was aided by a group called Serengeti Watch.

But after some extremely good and aggressive work, Serengeti Watch started to behave like Congress, more interested in keeping itself in place than doing the work it was intended to do. The first indication of this came when a Tanzanian government report in February, which on careful reading suggested the government was having second thoughts about the project, was identified but for some reason not carefully analyzed by Watch.

So while the highway is at least for the time being dead, Serengeti Watch which based on its original genesis should be as well, isn’t.

10: KENYAN TRANSFORMATION AND WORLD COURT

The ongoing and now seemingly endless transformation of Kenyan society and politics provoked by the widespread election violence of 2007, and which has led to a marvelous new constitution, is an ongoing top ten story for this year for sure. But more specifically, the acceptance of this new Kenyan society of the validity of the World Court has elevated the power of that controversial institution well beyond anyone’s expectations here in the west.

Following last year’s publication by the court of the principal accused of the crimes against humanity that fired the 2007 violence, it was widely expected that Kenya would simply ignore it. Not so. Politicians and current government officials of the highest profile, including the son of the founder of Kenya, dutifully traveled to The Hague to voluntarily participate in the global judicial process that ultimately has the power to incarcerate them.

The outcome, of course, remains to be seen and no telling what they’ll do if actually convicted. It’s very hard to imagine them all getting on an airplane in Nairobi to walk into a cell in Rotterdam.

But in a real switcheroo this travel to The Hague has even been spun by those accused as something positive and in fact might have boosted their political standing at home. And however it effects the specific accused, or Kenya society’s orientation to them, the main story is how it has validated a global institution’s political authority.

It isn’t just game viewing, it’s the extended stories about what you’re seeing that make the wilderness so fascinating.

It isn’t just game viewing, it’s the extended stories about what you’re seeing that make the wilderness so fascinating.