By Conor Godfrey

On the morning of March 22nd Malians woke up to discover that 20 years of stability and progress had been, temporarily at least, hijacked by a group of mutineers turned putschists led by a Captain Amadou Sanogo.

This was a punch in the stomach with no warning.

When I was evacuated from Guinea after a similar Coup in 2009, we traveled north through Upper-Guinea to Bamako, Mali.

On the Guinean side of the border, one gets shaken down every 50 kilometers by aggressive soldiers manning checkpoints on a sorry excuse for a main road.

As soon as you cross to the Malian side of the border, the road quality improves 200%, and the soldiers manning periodic checkpoints are friendly and helpful.

It was like a different planet.

This small anecdote conveys the crux of the sahelian surprise – this landlocked country with minimal assets was successfully bootstrapping itself out of desert poverty.

It was also a poster-child for the fruits of reasonably good governance.

This coup was not the result of long simmering ethnic tension, or gross mismanagement; it was a pseudo-spontaneous overflow of frustration by a group of junior officers and enlisted soldiers in Bamako.

More of an isolated mutiny that got out of control.

The explanations for the coup are all over the news: here and here you can find good articles on the acute causes.

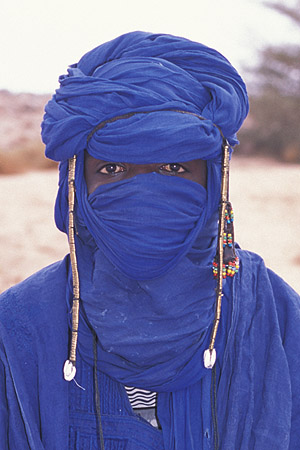

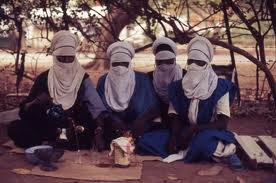

See my previous post on Tuaregs.

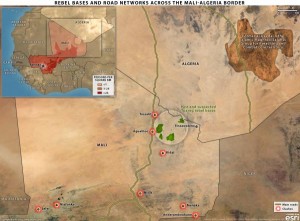

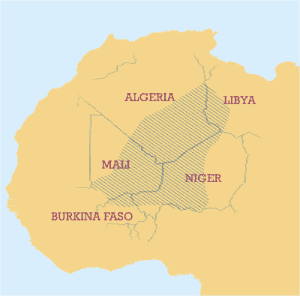

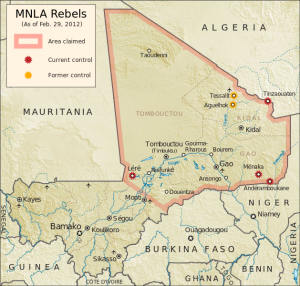

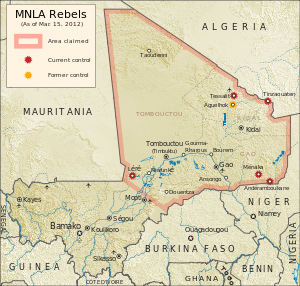

Essentially, there has been a full-fledged rebellion in the north of Mali since January, led by a Tuareg outfit known as the Movement for the Liberation of the Azawad (one of many Tuareg campaigns over the last few centuries….they are only called rebellions once there is an actual State to rebel against — I suppose.)

These rebels have inherited military equipment and wherewithal from the Tuaregs that fought alongside Gadhafi, and are essentially outgunning and outmaneuvering the uniformed Malian army.

The junior officers doing much of the fighting (and dying) in the North feel the Malian government has mishandled the rebellion, accusing them of sending poorly armed and equipped soldiers to face hardened and well armed rebels.

This issue is also magnified by the growing resentment of the Southern Malian population (where the overwhelming majority of Malians live) toward the rebellious Tuaregs in the North.

Most Malians are looking for a strong response.

(Whether this constitutes “support” for the coup is difficult to tell: here is a very intriguing set of posts by “Bamako Bruce” claiming widespread disenchantment with the previous government.)

Regardless, if soldiers continue to loot stores and government buildings, nebulous support from some Malian youth will likely evaporate.

I am going to go out on a limb regarding the outcome of this crisis, and I expect you all to write in angry comments if I am wrong…

My prediction is that this is going to blow over.

The coup leaders did not secure the backing of the necessary socio-political elements of Malian society (religious leaders, senior military figures, opposition groups), and now find themselves increasingly isolated.

Malians were enjoying the fruits of democracy (albeit slowly), and have no appetite for violence or prolonged instability.

They are simply pissed off that their government cannot get a handle on the conflict with the Northern rebels.

On that front, the Tuareg rebellion has done so well that there are now signs the rebel leaders want to negotiate from a position of strength and secure more autonomy and other perks before their success triggers the use of overwhelming force by Mali (perhaps financed and armed by international friends).

All of this spells a negotiated solution.

The coup leaders will try to secure a golden parachute by leveraging their ability to prolong the instability, and some of them may get one.

The rightful president of Mali, Mr. Amadou Toure (now either in hiding or under arrest), was due to leave office in weeks anyway, and will likely agree to leave power as scheduled and collect his prize from the Mo Ibrahim Foundation.

He will inevitably promise all sorts of populist goodies on his way out knowing that his successor will have to deliver on them.

This will pave the way for elections that will elect a candidate promising better equipment and training for the army, thus defusing the tension that brought the coup in the first place.

Of course, things could go south quickly as well.

Read this short piece of analysis by a risk consulting group.

While I think that the Executive Analysis scenario is unlikely, there are several points where my more positive projection could break down.

These mainly concern rebel and government choices regarding winding down or scaling up the conflict in the North.

The Malian government may need (strategically or because of popular pressure) to bloody the rebels before negotiating.

After all, the Tuareg rebels have claimed so much land in this campaign that they might be tempted to do so again the next time they are feeling aggrieved or restless.

This scenario could give the military government more time to maneuver, as it will be difficult to respond effectively to the rebellion if everyone is focused on elections.

My views are not necessarily the majority position. A darker prognosis can also be found here at African Arguments.

Mali is headed in the right direction. This, I think, I hope, is just a painful bump.

P.S. The Coup leader received military and intelligence training in the U.S.