One of Africa’s most iconic prides of lions were poisoned last week in the Maasai Mara, and it’s now time to implement Richard Leakey’s dream to consolidate all Kenyan wilderness under a single federal government agency.

One of Africa’s most iconic prides of lions were poisoned last week in the Maasai Mara, and it’s now time to implement Richard Leakey’s dream to consolidate all Kenyan wilderness under a single federal government agency.

Eight of the magnificent “Marsh Pride” were poisoned by Maasai herders, according to officials who have arrested two men.

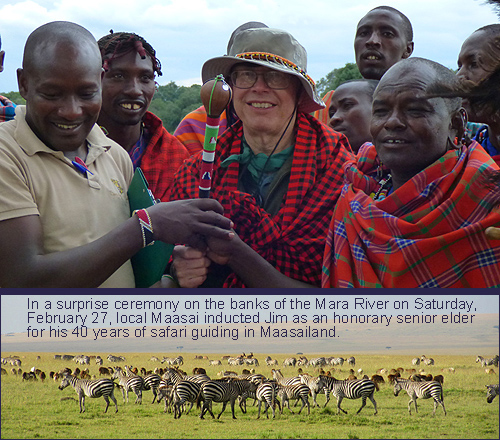

Animal poisoning in The Mara is not new, but this killing is receiving unusual attention since this is the pride featured in the BBC documentary, “Big Cats.” The pride has resided for my entire 40 years of guiding outside Governor’s Camp near the Mara River.

Many Maasai believe that protecting the Mara for wildlife/tourism is an unfair usurping of their traditional pastures. This conflict grows at the margin of seasons (which is now) when new rains sprout nutrient grasses.

The problem is not endemic to The Mara or Kenya but exists throughout all the rapidly developing lands of Africa. Ironically, the problem may be exacerbated by Kenya’s faster and broader development compared to many other African countries.

The situation unique to The Mara, though, is extraordinary. It’s a mess: an entanglement of personalities, politics and corruption the likes of which belong in a TV sitcom.

First of all, there really isn’t “A Mara.” Elsewhere in the continent there is “A Serengeti” or “A Sabi Sands” surrounding “A Kruger.”

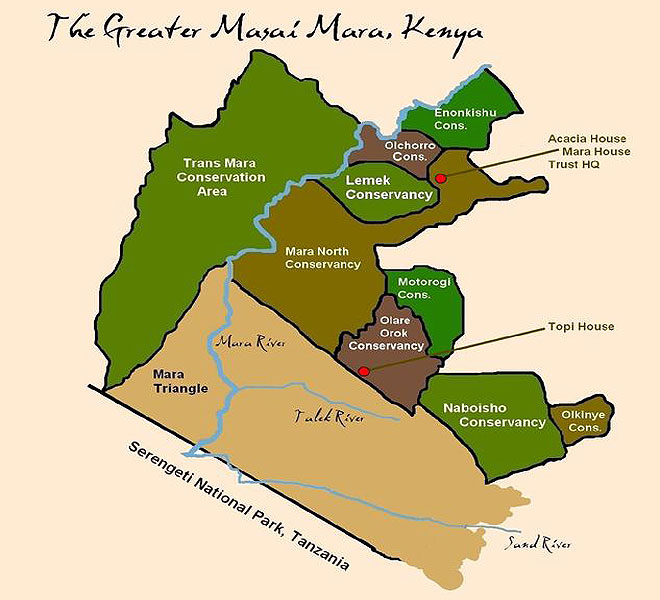

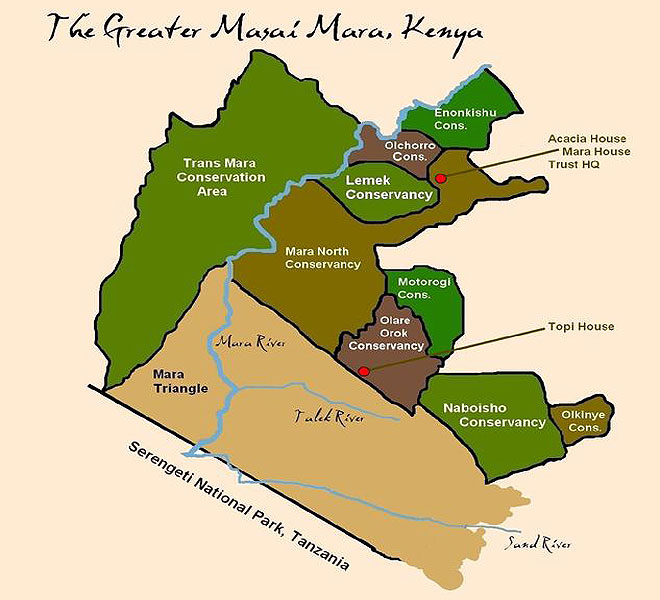

“The Mara,” instead, is a collection of government and private reserves each separately managed and funded. The map looks like a gerrymandered set of 10 districts in my dysfunctional state of Illinois.

“The Mara” is not a Kenyan national park: the main responsibilities for it rest with the county of Narok in which the wilderness is located. This is an freakish historical legacy of the local Maasai unwilling to share power or land.

Richard Leakey tried to change this decades ago when he was the country’s wildlife czar. He failed miserably, succumbing at the time to a very powerful Maasai politician, Ntimama.

Ntimama is today a very old mzee out of favor with the younger, more progressive regime in Nairobi. But it was only a few months ago that the old man resurrected the land issue of which the Mara is front and center.

The rectangular portion which borders Tanzania to the south is the “government” county reserve, but even that is divided into three administrative sections. The area to the north of the county land is made up of nine private conservancies, more than doubling government land.

It was the development of these northern private areas in the last 25-35 years that contributed so substantially to the increase of animal populations including the great migration.

(A similar situation exists with private reserves like the Sabi Sands which surround South Africa’s Kruger National Park.)

Traditionally all of these lands were used as pastures for cattle and goats by the Maasai. Had none of the lands been protected, the cattle and goats and Maasai would likely have eaten themselves out of house and home by now, identical to what you see today in so many other parts of Africa where overgrazing ends in societal suicidal.

From the point of view of the people living there, though, that’s not such a bad outcome if what comes next are highways and factories. IBM is still in the throes of a fraction-of-a-billion dollar deal to build a high-tech industrial park in what was once Kenya’s Tsavo wilderness.

I doubt you’ll find too many young Maasai today who will lament herding cattle for pennies a day if the alternative is writing computer code and driving to work in a Benz.

Equally sad, private tourism stakeholders are just as mercenary as the Narok Maasai. There have been periods of vicious competition among businessmen, some foreign nationals, vying for the best spots. In this management mayhem developed the private reserve map we see today, with little scientific or management rational and little or no interaction between the competing areas.

That spells disaster. BBC has the exposure to wander between reserve boundaries unimpeded, and thus the “Marsh Pride” became very special. But I’ve known several young field researchers who would have loved to work in the Mara ecosystem, but who turned to Tanzania instead because the politics and restrictions of working trans-reserve were too difficult.

The private reserves do everything themselves: anti-poaching, rules for wildlife management and intervention (several of the Marsh Pride that were recently poisoned were then treated by vets), fees and marketing. But the land has never been actually transferred from Maasai ownership: it’s leased, and that’s the private reserves greatest flaw:

Maasai owners could only be encouraged to compromise their age-old historical life style as pastoralists if they could be paid enough. For a while, they were. The revenues from tourism throughout the 90s were greater than the revenues from cattle farming.

But with political instability followed by terrorism which effected Kenya so seriously from 2007-2012, tourism revenues fell precipitously. Although safari revenues in neighboring Tanzania have planed or shown a slight increase, this has yet to occur in Kenya.

In their heyday the private reserves became extremely sophisticated, bettering the government reserves in anti-poaching and educational efforts. Like all bureaucracies, though, their appetite for capital grew well beyond the simple lease payments to the Maasai owners. Since 2008 virtually all the private Mara reserves have fallen into arrears.

Stefano Chile, the chairman of the second largest private conservancy, the Mara North Conservancy, wrote to supporters recently that “our ability to pay and cover all these costs is seriously challenged.”

He said the conservancy needs $355,000 to become sustainable, again. The first appeal for donations launched at least a month ago has raised only $13,000.

Cheli is one of the most creative and long-time entrepreneurs in the East African tourism industry, perhaps best known for building Tortilis Camp in Amboseli. But in my estimation this is way beyond his or any other excellent tourism manager’s job.

For one thing were a campaign like this successful it would hardly be the last time private reserve officials came to us hat in hand. Which of the nine reserves would you decide to support? I have a hard enough time juggling contributions to two public radio stations serving my area. If appeals came from nine of them, a distinct impression is created that nobody knows what they’re doing.

Collectively that’s the point, they don’t.

Private wildlife reserves have been a very important part of Africa’s conservation efforts for more than a half century.

But nowhere else in Africa is a collection of hodgepodge private reserves so terribly organized and so terribly suspicious and competitive with each another as in the Mara, and trying to treat them as charities is overwhelmingly impossible.

What will work is the Kenyan government getting serious. The photographer Jonathan Scott reported on his blog two days ago that may be happening.

From my point of view there’s only one answer. The government must take over the whole kitandkaboodal. This will really freak out the private reserve stake holders.

But it’s time they listened to themselves: if wildlife conservation is the goal, then look at Amboseli. Look at the Aberdare. Look at the heroic efforts in Nakuru. Look at all the other wonderful national parks in Kenya.

Frankly, it’s time the Maasai of Narok, and the stakeholders of the private reserves were all sidelined, and that the Kenya Wildlife Service takes the whole thing over.

Richard Leakey’s dream was right then, and it’s right now: The Maasai Mara National Park.

Tired but infuriated I watched the House Havoc to its end. Then just as my brain sensed a wee bit of insight a client sent me the Times’ article castigating tourists who drive too close to cheetah.

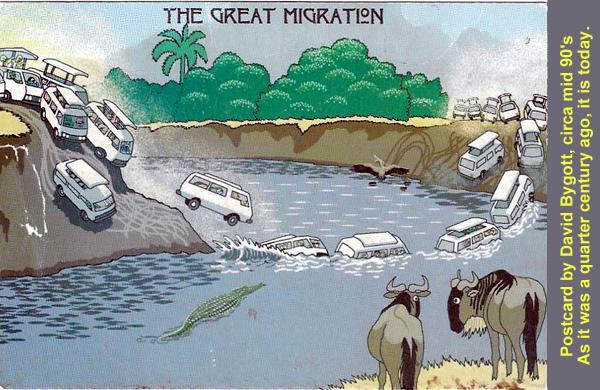

Tired but infuriated I watched the House Havoc to its end. Then just as my brain sensed a wee bit of insight a client sent me the Times’ article castigating tourists who drive too close to cheetah. I don’t like crowds… of people, that is. I take my rovers into tens of thousands of wildebeest, sometimes hundreds of thousands. My cars are often the only ones in view.

I don’t like crowds… of people, that is. I take my rovers into tens of thousands of wildebeest, sometimes hundreds of thousands. My cars are often the only ones in view. The “unlawful and

The “unlawful and  I was supposed to be in Paris with my wife celebrating our 50th anniversary. I’m in Dublin where I’ll be writing more about this interesting, unexpected journey due to Covid in later days. But today I just gotta write about Marriott!

I was supposed to be in Paris with my wife celebrating our 50th anniversary. I’m in Dublin where I’ll be writing more about this interesting, unexpected journey due to Covid in later days. But today I just gotta write about Marriott! Those damned kids! They ruined dinner once again!

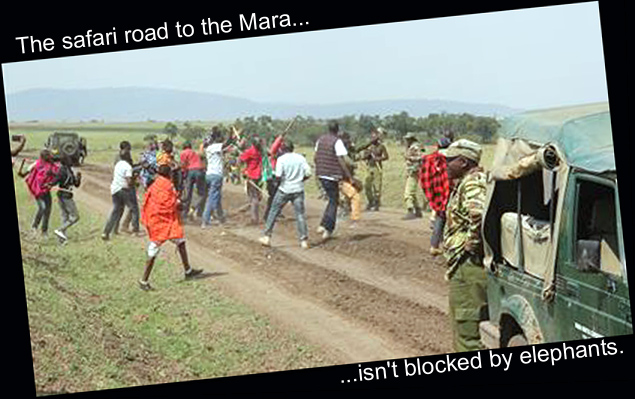

Those damned kids! They ruined dinner once again! The revolutionary fervor seeping from Hong Kong to Argentina to Mexico has infected Kenya’s most important tourist area, the Maasai Mara.

The revolutionary fervor seeping from Hong Kong to Argentina to Mexico has infected Kenya’s most important tourist area, the Maasai Mara. The man who organized the safari I’m guiding has been with me eight times. Only four others of the 12 people have been to Africa before, and Steve had a list of favorites that he wanted to share with his close friends.

The man who organized the safari I’m guiding has been with me eight times. Only four others of the 12 people have been to Africa before, and Steve had a list of favorites that he wanted to share with his close friends. Ole Kisemei took me to the highest point in the Mara this morning, Kileleoni. The view was magnificent, but what we saw going up and down was even better.

Ole Kisemei took me to the highest point in the Mara this morning, Kileleoni. The view was magnificent, but what we saw going up and down was even better. We had a Maasai guide for our final days in Kenya. There are about 500 guides in Kenya’s best game park, the Maasai Mara. Only three are women: “our” Lucy was one.

We had a Maasai guide for our final days in Kenya. There are about 500 guides in Kenya’s best game park, the Maasai Mara. Only three are women: “our” Lucy was one. There’s no more beautiful place now than Kenya’s Maasai Mara. Sweeping landscapes of dramatic hills and jagged mountains; valleys lush with acacia, fig and muratina forests and so many clear-running streams and rivers – it’s impossible to beat.

There’s no more beautiful place now than Kenya’s Maasai Mara. Sweeping landscapes of dramatic hills and jagged mountains; valleys lush with acacia, fig and muratina forests and so many clear-running streams and rivers – it’s impossible to beat.