The great wildebeest migration is the greatest wildlife spectacle left on earth and the main reason that visitors come to East Africa. Things are changing.

The great wildebeest migration is the greatest wildlife spectacle left on earth and the main reason that visitors come to East Africa. Things are changing.

“The wild beest migration is unexpectedly … back around Central Serengeti,” Tanzania Adventure Safaris newsletter reported a few days ago.

“As there have been good rains this year… the herds [are] moving all the way down to the short grass plains … when they would not be expected.”

The migration occurs in the Ngorongoro/Serengeti/Mara ecosystem, roughly a 200-mile vertical oval east of Lake Victoria. About 3/4 of this area is in Tanzania, and the remainder in Kenya as the Mara.

There are now numerous wildebeest migration watcher sites, such as “Herdtracker,” all of which I’ve found biased, incomplete or irregular at some point when I checked. Geared mostly to the particular camps or companies with which the site is associated, a snippet of where the migration is, is generally truthfully reported, but the overall picture is never explained.

With two million animals involved, there really isn’t a focal point for the migration. Moreover, at various times during the annual year’s migration, the great herds may be cleaved into halves or quarters traveling sometimes in nearly opposite directions.

Predicting where and when a safari can intersect the great migration was never an exact science but always a pretty good bet. The two million migrating herbivores involved eat virtually nothing but grass and grass grows when it rains and rain cycles were quite predictable.

In the north, in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, it rains almost every day of the year except in October and the beginning of November. The grass, though, in the higher elevations of the Mara isn’t quite as nutritious as the grass in the far south of the Serengeti. So even though grass is growing almost all the time in the Mara, if there is better grass to the south, that’s where the herds will go.

The circle of rain is like a big hula hoop with Lake Victoria as its center. The great herds move with the edge of that circle as it contracts into Lake Victoria until finally they get diverted to the last place in the area where it’s raining, the north of the ecosystem, Kenya’s Maasai Mara.

Sounds simple, eh? All you have to do is predict when the rains will stop. The herds then move north, sometimes frantically depending upon how quickly the rain turns off down south.

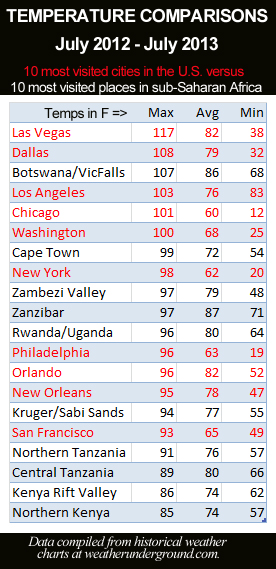

So a really safe bet was to visit Tanzania’s Serengeti really any time in the first half of the year (although February and March were always a sure bet), and Kenya’s Maasai Mara in July – October (although August and September were considered the best).

Didn’t happen this year.

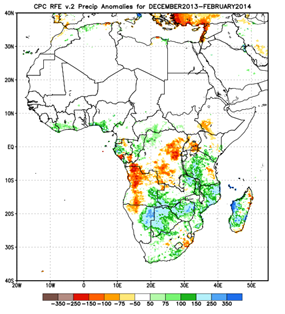

This October much of the central and southern Serengeti received up to four inches of rain. Normally there would be no rain at all.

Two things are happening:

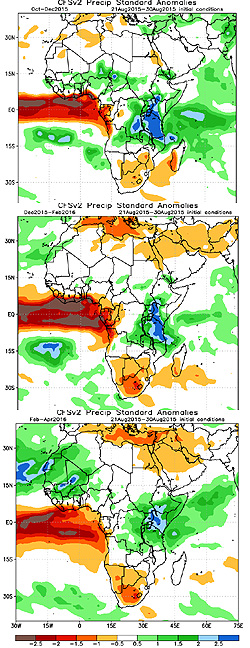

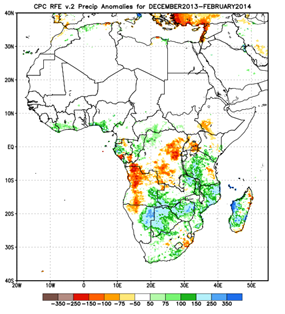

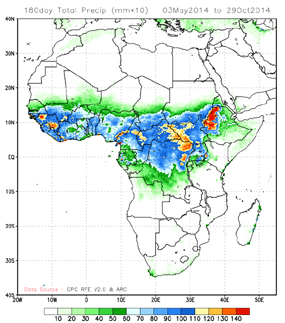

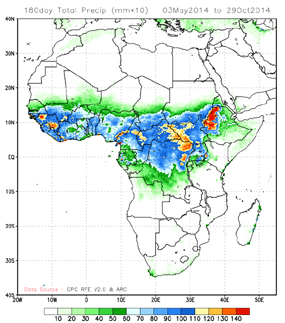

First, rains are much heavier than normal during the historically normal rainy season. You can see that from the NOA chart to the right. Green is a 100% increase over normal, so twice as much as usual.

Second, the rainy season itself is growing. You can see that from the second NOA chart just below the first. Green is a 50% increase over normal. Blue, which shows through much of the equatorial region, is a 100% increase.

More rain and a longer season is going to keep the wildebeest for a longer time in Tanzania’s Serengeti and delay their arrival and hasten their departure from Kenya’s Maasai Mara.

Is this a trend, or just something unusual for these past few years?

According to the Stockholm Environment Institute (weADAPT), one of the few professional meteorological organizations to study East African climate:

“…there has been an increase in the number of reported hydrometeorological disasters in the region, from an average of less than 3 events per year in the 1980s to … 10 events per year from 2000 to 2006, with a particular increase in floods.”

weADAPT and most organizations are concerned mostly by how this effects people, and the news in that regards isn’t good. Malaria, for one thing, will increase with increased temperatures and precipitation.

But the wildebeest and zebra love it. Their numbers are increasing, more and more grass is growing, and with time they’ll be spending more and more of their time in Tanzania rather than Kenya.

But at the same time as the rains increase there will be less of a need “to herd.” The animals may just start wandering, because wherever they wander, there will be food to eat.

The hard-wired aspect of wildebeest migrating — which we normally see as files of running animals — isn’t going to change or adapt as fast as global warming. We’ll always see them running, and it’s a magnificent sight!

But as it rains more and more, they might not have to.

The rains start north to south, and we traveled north to south and always seemed to be just a day or two ahead of the rains. It was so dry and dusty in Tarangire when we got there Monday that the interior of my room was 105F and my hands were dry after washing my face in the sink before I could get to the towel rack.

The rains start north to south, and we traveled north to south and always seemed to be just a day or two ahead of the rains. It was so dry and dusty in Tarangire when we got there Monday that the interior of my room was 105F and my hands were dry after washing my face in the sink before I could get to the towel rack. The worst locust outbreak ever seen in Africa, the most insidious virus ever known to man, the most flooding and worst earthquakes in history… then, bloodshed.

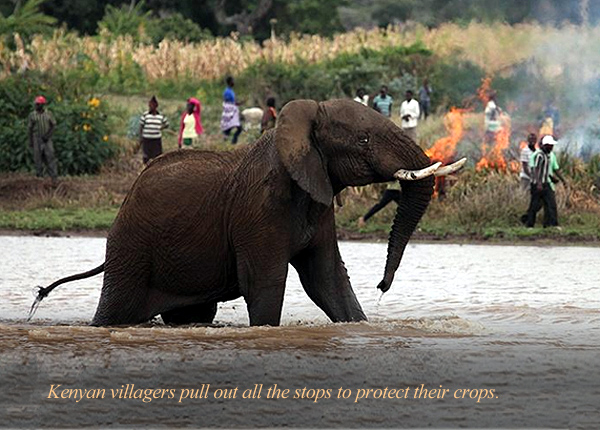

The worst locust outbreak ever seen in Africa, the most insidious virus ever known to man, the most flooding and worst earthquakes in history… then, bloodshed. It’s immoral to support saving wildlife at the expense of saving people. It’s that simple and today in Kenya I realized first-hand this travesty.

It’s immoral to support saving wildlife at the expense of saving people. It’s that simple and today in Kenya I realized first-hand this travesty.