Two African elections this week clearly show how democracy fails in societies with powerful chief executives.

Two African elections this week clearly show how democracy fails in societies with powerful chief executives.

Like the U.S. But more about that after discussing Africa.

This week’s elections in Zimbabwe and Mali have failed both their societies, for different reasons, and the result is arguably worse than had there not been elections at all.

In Zimbabwe the rigged election process reaffirmed the country’s despot, Robert Mugabe, and ensures the country will continue to slide into poverty and greater dependency upon its neighbors desperate that it doesn’t totally fail.

It’s interesting that Mugabe and thugs mastered the democratic process so well that despite this week’s travesty of popular expression, observers from as divergent organizations as the African Union and reporters for Reuters gave the process a pass.

It absolutely wasn’t fair. Imagine an election – officially stated – with 99.97% of the rural population voting, and only 68.2% of the urban population voting.

Get it?

What Robert Mugabe has become is an evil despot. This is pretty easily defined as an individual who concentrates power around himself and his thugs, and distributes whatever wealth can be extracted from the country into this small core of individuals.

At the expense of everyone else in the population, even those who supposedly voted for him.

He absolutely does have solid support from Zimbabwe’s poor and rural populations, who are thrown pieces of bread (the land of white farms) just like Marie Antoinette did to stave the French revolution.

And essentially uneducated and untrained, a piece of land is a gold mine, but what it means for the tens of thousands of rural Zimbabweans who have benefitted from this policy, is that they will never have tractors, will never have schools, will never have hospitals or roads or a better life beyond their tiny plot of land.

Yet their ecstacy at this gift from Daddy is profound. And their xenophobia and racism is ripe for plucking. And even so, even with 99.97% of them “voting,” they wouldn’t have been the majority if the more educated urban populations were given their voice.

And, of course, 99.97% of them didn’t vote. Many of them can’t read and there weren’t enough polling stations in the country to handle that number of actual voters. The irregularities in this “election” were profound.

Yet it was “democratic.” Zimbabwe’s urban population rolls were restricted by techniques strikingly similar to dozens of new American voter registration laws. If it’s democracy in Texas, it’s democracy in Zimbabwe.

In Mali – often championed as a model for democracy by westerners – another near perfect election process has resulted in an effective tie. This is something democracy can’t handle. It screwed it up in Bush v. Gore, and it screwed it up in Kenya’s recent election, and now Mali’s future becomes terribly problematic.

Ibrahim Boubacar Keita (IBK), a former prime minister in better times, seems to have received 50.+% of the vote, which would effectively make him the chief executive without a second run-off election.

This, by the way, is the identical situation that occurred in Kenya in March, where the victors were ultimately declared the winners with 50.07% of the vote.

In Mali, the election process was truly fair in my opinion. If there was any fault to the process, it was that the serious opposition from the desert peoples and those involved in the recent insurgency was not voiced. In part, because the insurgency continues and the insurgents didn’t want to participate.

But of the society held together by the French Foreign Legion, a sort of muscular gerrymandering, the elections were remarkably free and transparent.

But now what? Within the margin of error of any scientific study, no one really won, but democracy mandates that someone win. If this were in Europe or Israel, it wouldn’t matter so much, because the chief executive for whom the election was held is not so powerful.

But in executive democracies, where the chief executive like President Obama holds so much power, one of the sides wins and one of the sides loses. Definitively.

And down the road that leads to polarization, friction and radicalization of power blocks that might otherwise be able to compromise.

Had America had a parliamentary democracy rather than an executive presidency, I believe that we would never have gone to war in Iraq and Afghanistan. The challenge of modern democracy is to create workable amalgams of power in societies with large and nearly equally opposing views. That’s not possible in societies with a powerful chief executive.

This is the case as well in Kenya, where ethnicity and corruption is now on the rise after decades of decline, and where Mali is likely now doomed to become a war zone for generations.

Neither Kenya or Mali will be able to traumatize the world as much as America did after Bush v. Gore. But all three examples show how ineffective, perhaps counterproductive, democracy is when the society has a powerful chief executive.

The analysis seems much simpler with Mugabe. When evil masters the process, in this case democracy, the ends justify the means and essentially emasculates the idealists who proclaim the process. Yet on closer reflection it’s clear had Zimbabwe not had a powerful chief executive style government, Mugabe may not have lasted.

The lesson seems starkly obvious to me. Democracy is a bad idea for societies with a powerful chief executive. Parliamentary democracies may be good; presidential democracies are not.

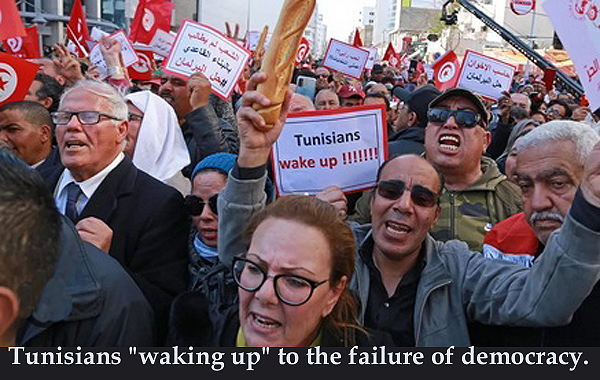

Tomorrow the modern African country that started the Arab Spring in 2010 will officially end democracy in Tunisia. This is neither a coup or proletarian revolution. It’s what the people want.

Tomorrow the modern African country that started the Arab Spring in 2010 will officially end democracy in Tunisia. This is neither a coup or proletarian revolution. It’s what the people want. Western fixation with terrorism at the expense of poverty and basic human rights is finally coming home to roost in Africa.

Western fixation with terrorism at the expense of poverty and basic human rights is finally coming home to roost in Africa. The violence is over in South Africa. More than 200 people have died and the Washington Post estimates the looting and physical damage “exceeds several billions of Rand.”

The violence is over in South Africa. More than 200 people have died and the Washington Post estimates the looting and physical damage “exceeds several billions of Rand.” The Devil’s rising.

The Devil’s rising. In a scene that could well be that of Donald Trump in a few years, Jacob Zuma was put in jail Wednesday, and the days and weekend that followed exploded in violence. The South African military has now taken to the streets to contain the fighting especially in Johannesburg and Durban. Six protestors are confirmed dead and many more assumed hurt.

In a scene that could well be that of Donald Trump in a few years, Jacob Zuma was put in jail Wednesday, and the days and weekend that followed exploded in violence. The South African military has now taken to the streets to contain the fighting especially in Johannesburg and Durban. Six protestors are confirmed dead and many more assumed hurt. Elections, 0. Popular Uprisings, 3 (or more). Are we experiencing a new Arab Spring? Or better, a new Human Spring?

Elections, 0. Popular Uprisings, 3 (or more). Are we experiencing a new Arab Spring? Or better, a new Human Spring? Much of the world takes a holiday, today.

Much of the world takes a holiday, today.