Pretty story but not very effective: recruit Maasai morani – the legendary warriors that are expert lion killers – to protect lions. Sort of like hiring the ultimate teenage hacker to protect HSBC.

Pretty story but not very effective: recruit Maasai morani – the legendary warriors that are expert lion killers – to protect lions. Sort of like hiring the ultimate teenage hacker to protect HSBC.

Lion numbers are dropping alarmingly, and better than any other great African savannah animal lion are a true indicator of the health of the African wild.

Unlike elephant or rhino – which are being poached at alarming rates even as their wild population increases – lion are the top of a complex pyramid of life and while masters of their position are beholding to the foundations.

Many important studies have suggested unusual reasons for the decline over the last several decades, but it now seems clear that the reason is quite simple: the wild is contracting.

Of the big cats, only the solitary leopard seems capable of adapting to a world increasingly dominated by man. The others – and especially the lion – seem unable to establish any relationship with a world increasingly dominated by homo sapiens except to war with him.

And the greatest battles are those legendary pitched posses of Maasai warriors in Old Testament regalia: Maasai don’t kill any animals for fun or food. They kill in retaliation, as if a lesson can be learned.

When a lion threatens their goats or cattle Maasai go on a war path, and some of the most spectacular stories out of Maasailand are of the greatest and most noble of the lion hunts. In the old days headmen were often determined by those who successfully killed a lion.

And remember, this isn’t with a gun. It’s with a spear and a knife.

Maasai and lion have coexisted for centuries because they use the same habitat. The grazing necessary for Maasai stock is the same that all sorts of antelope on the plains need. When there was enough for all, everyone was fat and sassy. There were enough antelope for the lion that much preferred them to a smaller goat or a larger and lanky cow.

Maasai cattle were bred not for meat but for milk. The cost/benefit ratio of a lion bringing down a Maasai cow compared to a wildebeest was no contest. The wildebeest could be killed more quickly (cats kill by strangulation, and this takes enormous time with a cow) and the dinner table had lots more meat for the effort.

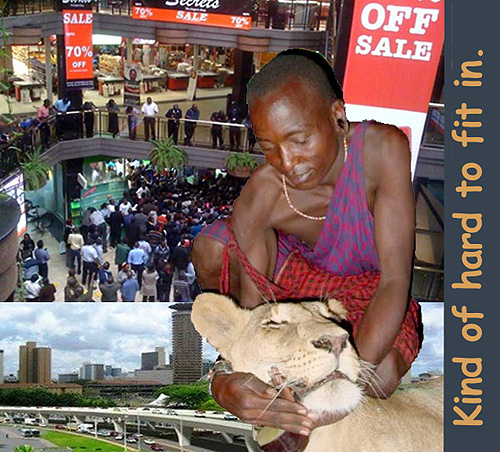

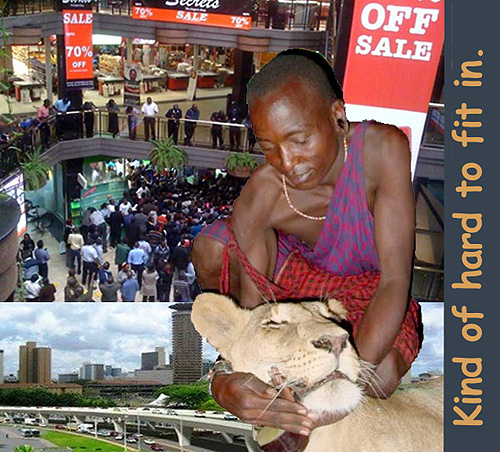

But times changed. And note, too, that traditional Maasai are declining just as rapidly if not more so than the wild animals in their homelands. And maybe for the same reasons:

Shopping malls, highways, schools and hospitals, modern farms.

It takes no kopjes scientist to know where this is going.

So arise the Lion Guardians! This high profile NGO in East Africa was formed by dedicated conservationists “to promote and sustain coexistence between people & wildlife through ecological monitoring and local capacity building.”

IE: Pay Maasai morani to protect rather than kill lions.

It’s noble, yes. And anything that can give paid work to young traditional Maasai who are themselves increasingly threatened, is good. Especially in the West Kilimanjaro area adjacent Amboseli National Park.

This area is a microcosm of lion difficulties everywhere. Amboseli is one of the most important and well-known big game parks in the world famous especially for its elephant. Elephant are being threatened today by increased poaching, but their numbers are still increasing in places like Amboseli, because … well, elephant get their way.

But Amboseli is surrounded by an increasingly developed agriculture, particularly just to its south in Tanzania. The highlands of Kilimanjaro are perfect for wheat and other cash crop farming.

The towns of Arusha to the west and Moshi to the east are expanding rapidly. The roads are being paved.

All of this – not just farming – needs water. This is draining the existing aquifers and Amboseli is becoming drier and drier. This is a death sentence for much game like buffalo and wildebeest. The increased elephant population results in deforestation, and combined with the loss of aquifer power the reduction of forests is terrible for impala, duiker and a chorus of tiny things like voles and mice that animals like hyaena and jackal need to survive.

So you see … or don’t, so to speak, as time passes. No traditional food, Mr. Lion heads south to where Maasai live with their goats and cattle.

Lion Guardians believes in conserving the wild and in promoting tourism. It’s a two-pronged argument that often sticks it to itself. Tourism is one thing. Conservation is another.

There’s no doubt that tourism suffers as there are fewer lions to see in the wild. But tourism is already suffering drastically, mainly from the political situation in Kenya linked directly to the violently unsettled situation in Somalia. We hope this is temporary.

Whether temporary or not, conservation is another matter.

I grow quite sad thinking the day may come when there won’t be lions in the wild as I’ve seen all my life. But it’s hard to argue to save the lion with the same powerful scientific arguments for saving the Amazon rain forest. We know almost everything possible about lions and the African savannah. There are of course mysteries yet to be revealed … but not many.

The forest provides my oxygen. The veld powers my imagination – no small thing – but not exactly biological.

And what we know mostly is that Maasai recruited to protect lions are getting mauled, and in the end, not saving any more lions and not convincing their young teen Maasai not to go to the city and become certified public accountants.

That’s life.

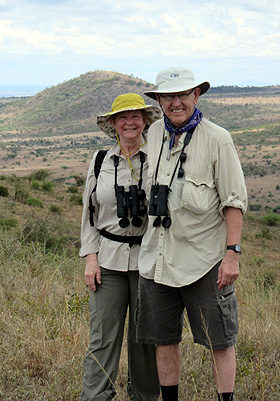

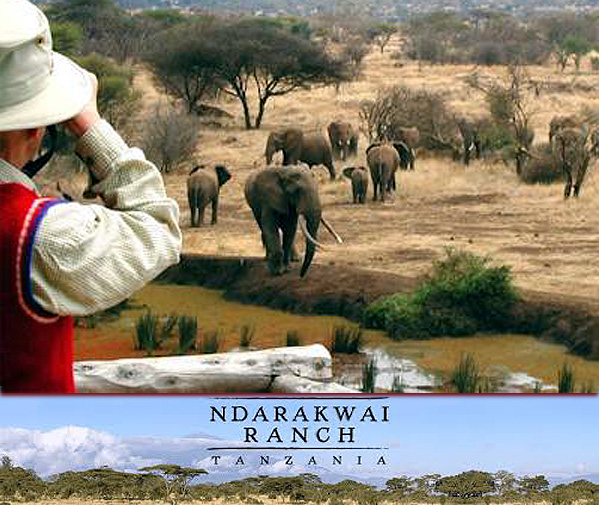

Today I begin guiding a private safari of a family from Boston, a wonderful itinerary longer than the average which visits virtually all of the best places in Tanzania.

Today I begin guiding a private safari of a family from Boston, a wonderful itinerary longer than the average which visits virtually all of the best places in Tanzania.