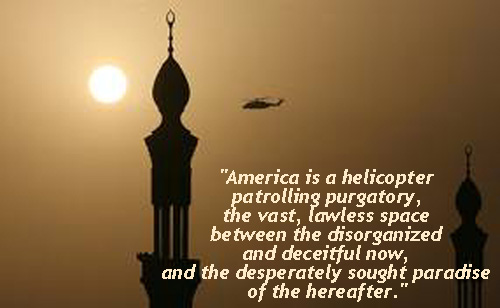

To a young apolitical Iranian woman, America is an army of helicopters ruling purgatory, patrolling the vast, lawless space between the disorganized and deceitful now and the desperately sought paradise. This wondrous insight comes to us thanks to the Zanzibar Film Festival which opens this weekend.

To a young apolitical Iranian woman, America is an army of helicopters ruling purgatory, patrolling the vast, lawless space between the disorganized and deceitful now and the desperately sought paradise. This wondrous insight comes to us thanks to the Zanzibar Film Festival which opens this weekend.

(For a broader summary of the festival, please read my Tuesday blog.)

“Invitation” is a film by Payam Zeinalabedini, an Iranian with a very limited budget. It’s not going to win any technical awards, and as you are carried along by the lilting, beautiful girl’s voice over the film’s haunting music, it becomes hard to “translate” the very poor English subtitles. But please stick with it, and forget the subtitles if you must. It is absolutely a film that every American should watch.

Watch it now, by clicking here, or come back to it, later. It is 30 minutes long and gives us Americans a widely held view of ourselves from the outside.

In a larger sense I think this is why so many Americans love Africa. There is something that we immediately identify with every moment of new experience, whether it be vast Midwest-like plains or thousands of animals. (American’s empathy for animals is legendary.)

And I’d like to think a few clever Iranians understand this, too. Payam’s film has shown in a few other festivals, but its technical merits are wanting. If shown, for example, in Milwaukee or Austin, it would probably fall flat as poorly made propaganda. But the characterization it makes of America will not offend an audience in Africa. And obviously it’s not intended as propaganda, there.

Africa has manipulated America well, for both America and itself, for several generations. Africa knows the good we have, and the bad we seem unable to shake. And because the film really does lack the technical merits of so many of the other entrants in the festival, I have to believe, too, that the Africans running the festival are doing exactly what the Iranians are:

Trying to send us an important message. A post card, if you will, of an essentially apolitical Iranian girl of her journey into Iraq. In a way that won’t evoke our defensiveness before we absorb it. ‘Someone,’ I can imagine them saying to themselves, ‘has to let America know what’s happening.’

Filmed in 2008 it is a story of this young lady making the trek to the holy Shiite shrine in Karbala, Iraq. We never know her name, or the name of her grandmother who she invokes constantly as her mentor and inspiration and the assumed recipient of her remarks.

In fact, throughout the film’s crowded voyage through humanity, no one offers names. At the Iraqi/Iran border where American soldiers finger print and eye scan all pilgrims, names are clearly forged or just made up. Except for imams and holy historical figures, names aren’t used, not even when trying to check into an inn for the night.

The film becomes a documentary of crowds of nameless pilgrims wandering towards the shrine, in a sort of hapless pursuit that things holy must be better.

The Iranian woman narrator has paid an Iraqi tour company for the trip, as have hundreds if not thousands of other Iranians in lines of buses coming out of Tehran. But when the convoy reaches the Iraqi border, the comfortable vacation turns into a horrible expedition.

It’s raining and cold. Compared to Iran’s paved roads, Iraqi’s dirt tracks are terrible. And dangerous. The girl explains that Iraqi security personnel must join the bus groups to guard the continuing journey, because it’s considered so dangerous.

Waning daylight infuses the “second-hand Iraqi” buses bereft of working windows or adequate heaters as the convoy pushes deeper into Iraq. They pass Tikrit, and the narrator turns her camera at Saddam’s palace, but it passes quickly out of view as something no longer meaningful.

It’s dark, cold and still raining, and the colored often neon lights that poke out from villages along the way seem like circuses or game parlors. The narrator remembers the tracer lights of Iraqi aircraft over Tehran during the great wars. She was very little, and she remembers her grandmother telling her to run to the shelter.

Then the tour bus gets stuck in the mud, in the dark, cold and rain. The Iraqi security officer orders them to stay in the bus “And don’t sleep! It’s dangerous!” By the broken English subtitle, she says mournfully, “Grandma, I now know what anxiety for the future means.”

The next day she sees lines and lines of Iraqis walking on the muddy sides of the road to the shrine and feels embarrassed with her fortune. “I am not vengeful,” she begins, invoking the long wars between the two countries, “and I wonder if I should get out and walk with my brothers.”

Americans – which are never shown – are omnipresent, but as if in another dimension, outside real peoples’ realities. At one point, the security officer accompanying her in her bus warns her not to take pictures or use her cell phone, because Americans “have X-rays and we’ll all then get arrested.”

As they approach Karbala in the darkness and drizzle, the sounds of excited pilgrims increase. There is self-flagellation and ominous and aggressive dancing common to this sect of Shiites, unhappy crowds, mixed and uncoordinated singing and shouting. They walk pass dilapidated or bombed out structures as the throngs of people move towards the only lighted structure in the area, a yet distant giant Christmas-lighted mosque and shrine.

As they approach Karbala in the darkness and drizzle, the sounds of excited pilgrims increase. There is self-flagellation and ominous and aggressive dancing common to this sect of Shiites, unhappy crowds, mixed and uncoordinated singing and shouting. They walk pass dilapidated or bombed out structures as the throngs of people move towards the only lighted structure in the area, a yet distant giant Christmas-lighted mosque and shrine.

They decide to check-in to their inn before going to the mosque. The electricity is erratic and there is no light in the cold, rainy street. Yellow light peeps out from shuttered windows. When they finally locate their presumed overnight lodging, they discover there’s no room for them at the inn. And there’s no representative around from the travel agency that took their money to complain to.

“This is Karbala,” the innmaker intones, “go to Paris, go to the Emirates if you want a room!” The girl remarks they can’t even find an internet café, because there’s no electricity and no computers. She remarks with the first bit of political overtones that this is the country that was supposed to have a nuclear bomb, and they don’t even have working computers!

What she had hoped would be a joyous excursion has become a nightmare. She finds an Iraqi who has the authority to allow her to film inside the shrine, but his laptop doesn’t work so he can’t give her the necessary permit. She finds a laptop from a fellow Iranian traveler, and the official creates a permit using Word.

Suicide bombers have attacked nearby mosques. There are sirens and flashing lights, and suddenly American soldiers who are never shown, though. No one seems to care. “This country is conquered by Americans,” she says as if only realizing it herself, now.

Finally she gets inside the mosque. The light is bright, almost blinding. Most faces turn away from her camera. Those that don’t reveal fear, anger, perhaps terror.

She gets in a line of congested movement towards the shrine, the object of the trek. The orderly movement forward is interrupted by security officials frisking entrants. Inside, she says, “Grandma, perhaps it was your prayers that got me here, but now I’m entrapped among the security Army of Blasphermers.”

“I feel I am supposed to see and hear” inspiration or something religious, and then her voice is drowned out by the sounds of helicopters going around and around, closer and closer, louder and louder.

This is the view of Iraq by a young Iranian. I don’t consider this propaganda, although I think it quite fair to presume the film maker had an agenda in mind. But strip away the commentary and subtitles, and just take the scenes shown for what they are:

A country in endless mourning, restless and lawless, pitifully unfulfilled.

Ready to either implode completely or explode entirely.

An American watching this film must wonder what the hell we’re doing there. We’re not bringing peace, and we’re certainly not bringing prosperity or any measure of happiness. If our national security goal is to impede harm against us, we’re certainly not doing it by making friends. You could not live in Karbala without hating America.

Nevertheless, if this has “kept a lid on terrorism” one wonders if the oppression this thrusts on the peoples of Karbala is fair strategy. In a tit-for-tat body bag game, we’re winning. But one wonders if the game weren’t played at all, if the numbers of dead, injured and unhappy would be infinitely less.

We have turned a once joyful religious trek undertaken for centuries into a modern horror film.

Who cares that an elephant eats 150 pounds and not 250 pounds per day; or whether the peak of the dry season somewhere is October not September; or whether the start of a river is some unknown spring in the wilderness rather than a branch of hundreds of springs or rivers; or whether a huge part of Africa is independent or a part of Zambia?

Who cares that an elephant eats 150 pounds and not 250 pounds per day; or whether the peak of the dry season somewhere is October not September; or whether the start of a river is some unknown spring in the wilderness rather than a branch of hundreds of springs or rivers; or whether a huge part of Africa is independent or a part of Zambia? Halting abusive and dangerous behavior may take nothing more than showing that behavior to the abuser.

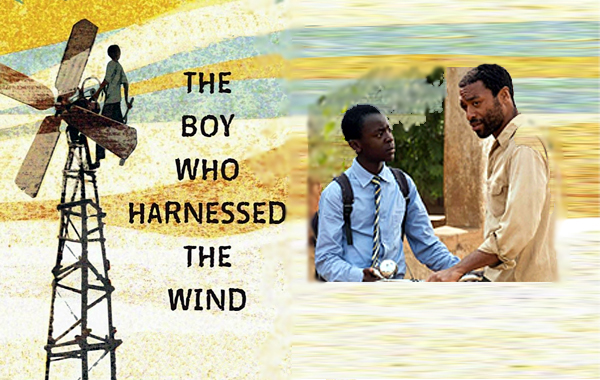

Halting abusive and dangerous behavior may take nothing more than showing that behavior to the abuser. Often children do better in stressful situations than adults. Children take greater risks, shedding the additional stress adults acquire from repeated failure. When stories embodying this are set in Africa and the child succeeds, big tears are shed.

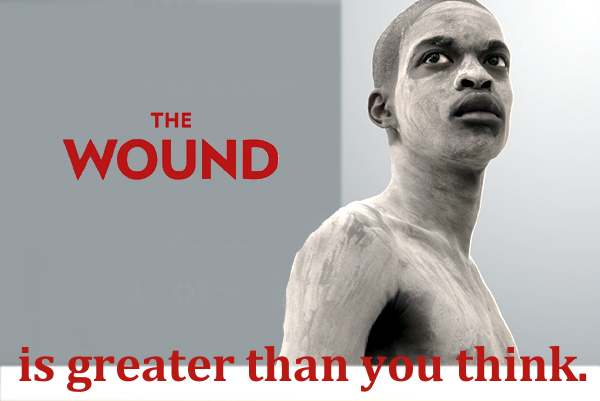

Often children do better in stressful situations than adults. Children take greater risks, shedding the additional stress adults acquire from repeated failure. When stories embodying this are set in Africa and the child succeeds, big tears are shed. Today cast members of South Africa’s entry for the 2018 Oscars best foreign film of the year

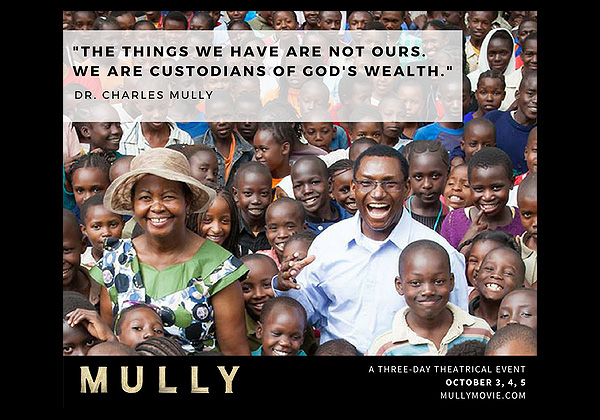

Today cast members of South Africa’s entry for the 2018 Oscars best foreign film of the year  There have been several outstanding Kenyan films which made it to the Oscars. The current Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Film from Kenya is not one of them. Beware.

There have been several outstanding Kenyan films which made it to the Oscars. The current Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Film from Kenya is not one of them. Beware.