Often children do better in stressful situations than adults. Children take greater risks, shedding the additional stress adults acquire from repeated failure. When stories embodying this are set in Africa and the child succeeds, big tears are shed.

Often children do better in stressful situations than adults. Children take greater risks, shedding the additional stress adults acquire from repeated failure. When stories embodying this are set in Africa and the child succeeds, big tears are shed.

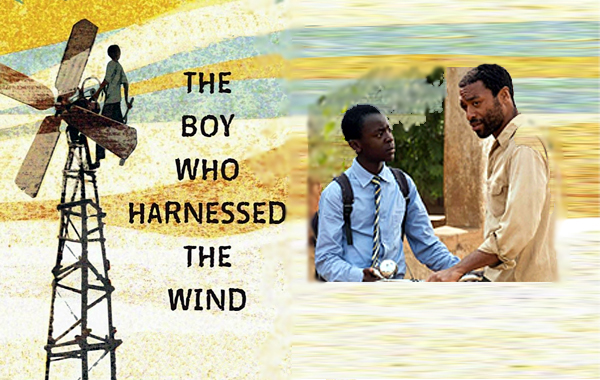

Netflix announced March 1 will be the debut for The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind, the first major film ever made in Malawi. Directed by Chiwetal Ejiofor who received Academy and Golden Globe awards for his star performance in 12 Years A Slave, it’s not as politically correct as it seems.

Nevertheless, big tears will be shed. Do I sound a wee bit cynical?

Like anyone not actually associated with making the film, I’ve not seen anything but the trailer. The film is based on a book published in 2010 which gained widespread acclaim by recounting the true story of William Kamkamba, who until his fame lived in a village in Malawi.

The true story of his ingenuity creating a wind-driven water pump for his village catapulted him to stardom, attracted much attention and capital and four years later he graduated from Dartmouth. He now works for a global NGO focused on bringing digital and internet services to rural communities around the world, principally in India.

Chiwetal Ejiofor’s interest was not from original research. It followed principals of Ted Talk, Dartmouth and Google who aggressively supported Kamkamba over the last decade. It’s the perfect story of rags to riches of someone who seems like a genuinely nice guy who also happens to be very smart.

The book and the story and Kamkamba’s life is all good news. It parallels the psyche of 12 Years A Slave whose happy ending is something every human craves to know.

But particularly at this time in world misery, I’m on guard against the too-goody account. I’ve learned over forty years that the vast number of small African missions launched from abroad, almost exclusively from religious-based organizations, have impeded rather than aided African development. From a long-term perspective they exclusively benefit the doers, not the receivers.

Shedding big tears is often a very personal, introspective cleansing of individual guilt: “My God! I knew how terrible Africans lived, but thank goodness they figured out how to make water pumps!” So now we can pass right over the need for global redistribution of income.

The threshold between telling a true story and embellishing it for greater effect breaks the reality that the true story is an infinitesimal representation of reality. Breaking the threshold denies real remedies for whatever the story purports to solve.

I wish that The Boy Who Harnessed The Wind came to us as fiction rather than a “true story.” As fiction it could be uplifting and a source of hope. But as a true story embraced by the super privileged Wealthy of the West, it coopts the aggressive action that the developed world must take to lift up the developing world.

I didn’t feel this way immediately on learning of the film. But there are rumblings in Malawi.

For some reason much of the film is in a local Malawian language with English subtitles. When asked about this Ejiofor told ScreenDaily, “There was no way around it. It was clear from the beginning that, if this film was to be embraced, it would need to be made that way.”

That’s not an explanation. I love listening to the melodies that African languages sustain gone from the harsh modern languages, so it’s actually something I’m looking forward to. But why did Ejiofor think it so important?

The simple reason is authenticity, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Until Malawians started to criticize Ejifor for his poor and unschooled use of the language:

Rosie Blunt of BBC News reported Friday right after the trailer for the film was released that the film “has garnered criticism over its poor use of Chichewa, Malawi’s official language aside from English.”

Further down her report are copies of tweets from Malawians whose criticism is considerably harsher, including an indication that no true native speaker in the film speaks the language natively!

This is important, because the film’s single greatest producer is BBC Films.

You may consider this a minor detail, and I eagerly look forward to watching the film. But it’s just the kind of red flag that fires my furry when western productions of Africa’s “good news” gets too embellished.