Today cast members of South Africa’s entry for the 2018 Oscars best foreign film of the year were herded into a “safe house” to protect them from growing threats against their lives.

Today cast members of South Africa’s entry for the 2018 Oscars best foreign film of the year were herded into a “safe house” to protect them from growing threats against their lives.

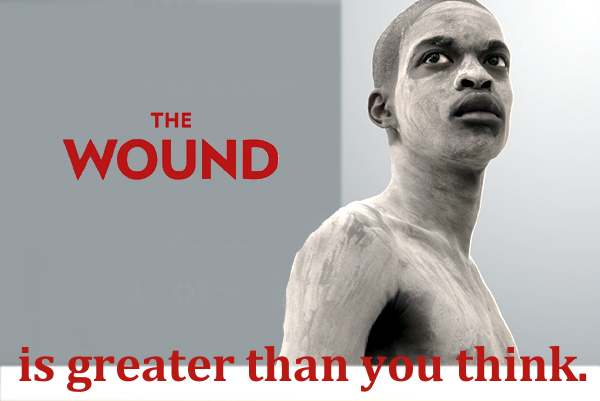

The “Wound” (“Inxeba” in native dialect) is a film about a young urban gay factory worker in South Africa who returns home for the traditional circumcision ceremony. Gay relationships are renewed among mentors and initiates suggesting this has been going on for years. In this particular year, though, the closets crumble. Some are outed threatening traditional marriages, parents are scorned and disgraced and the film ends in a quagmire of depression and loneliness.

This is a change in South African culture. Why now?

Although the film racked up an impressive string of awards, and although most reviewers worldwide gave it a positive rank, it was notable that American critics so struggled with the movie their reviews were often unintelligible.

The Times restricted its scant criticism to the movie’s cinematography. In some cases critics were so incapable of deciding what they really felt, reviewers like Guy Lodge in Variety sunk into simple rudeness. Lodge concluded the film will “bleed” well into the festival circuit.

The reason American critics are so befuddled, and the reason that the noble and by all means not-all gay cast of the film are in mortal danger in their own country, has to do with the West being so powerful.

Americans’ acceptance of sexual variations is recent. South Africa and many other parts of the world have a much longer history of accepting LGBTs. Cecil Rhodes, one of the country’s most historic and powerful figures, was openly gay in the late 19th Century and retired comfortably in the 1890s to a beach house with his boy lover.

The American neo-con/ult-right/evangelical movement has a very powerful impact worldwide. I’ve often written about how it’s so tragically impacted Uganda and Rwanda, for example. The success of this diabolical if deranged movement in Africa is, in part, because of its failures at home.

And now it has another success in South Africa. The attacks on Inexba do not reflect the rainbow society of South Africa which has been evolving for several hundred years. Instead, it resurrects much older, once anachronistic and very narrow Xhosa cultural views about sexuality. Nelson Mandela himself a Xhosa joked publicly about many of the old traditions which technically violated an ultimate Xhosa taboo against speaking about its traditions.

The antagonists in Inexba are American influenced modern South Africans somehow still functioning within their ancient traditions. That is a brilliant accomplishment by all the South Africans involved in this film, because it’s so unlikely.

Modern Africans and modern folks from all emerging societies don’t “go back.” Of course there are some who flee modernity, but they are far more unusual and infrequent than suggested by the unschooled critics of Inexba. Inexba is as uncommon a South African story as American Dolores Hart decamping to a monastery is American.

The hateful and classic oppressed sexuality of several of the main characters doesn’t reflect traditional South Africans. It’s a product of South Africa merging into the global society which is so dominated by many things bad from America and The West.

A few years ago South African actors wouldn’t have had to worry about threats on their lives for having successfully done a job like this. “Beauty” is only seven years old. The 2003 South African documentary “State of Denial” put all the dirty laundry of AIDS onto the screen. The cast and film-makers of those films flourish – they aren’t being hunted down. There wasn’t a South African homophobia as vitriolic as that expressed against this film, today.

But today is a different. Inexba’s story is a story infected by American duplicity and immorality white-washed with a splash of evangelical religion. It’s brilliant and I understand why it so confuses Americans. They try to view it in their own American context, and by so doing miss how dangerous that context is.

Hi Arusha,

A friend passed along your piece to me, and I read it with interest — I’ve been eagerly following stories of the film’s reception in South Africa, and the ensuing mixture of resistance and defence it has encountered, and enjoyed your insights on that complex matter.

I do think, however, that you’ve slightly misrepresented my Variety review: I’m sorry that you read it as rude, since I love the film, and only meant for the review to be highly complimentary. The “bleed” line was merely a pun on the title — Variety house style is big on such puns — and was meant to allude to the film’s visceral, deep-reaching impact.

Lastly, while I agree that the film can be read differently across different cultural lines and contexts, I’d like to clarify that I’m not American — I’m a South African, now based in London. Variety is a US-based outlet, but we have an international team of writers.

Anyway, thank you for writing with such care and nuance about this rare and wonderful film. It was a great read.