I don’t like crowds… of people, that is. I take my rovers into tens of thousands of wildebeest, sometimes hundreds of thousands. My cars are often the only ones in view.

I don’t like crowds… of people, that is. I take my rovers into tens of thousands of wildebeest, sometimes hundreds of thousands. My cars are often the only ones in view.

It’s selfish and egotistical, perhaps pridefully arrogant. We handful of guides with the skills and experience to find the calving fields represent an extremely small group of tourists. It’s hard to get there, not without risk since there’s no roads or tracks and sometimes, in fact, we don’t find them.

Rather, what the mass of tourists usually sees was truthfully documented in last night’s PBS premiere of this season’s ‘Nature,’ Running with the Beest.

But without that mass tourism, my explorations through the remote and Elysian Lemuta, Ndutu, Gol, Kusini and Keskesio plains could be badly impacted. If the herds aren’t protected in the Mara, their furthest northern migration point, their entire existence could be truly threatened.

The life cycle of the migration – and the modern day threats to it – are ridiculously complicated, and for a quick 50-minute discussion it wasn’t a bad introduction.

As a documentary, though, it was pretty amateurish, grazing over really complex issues with a trendy style of presenting problems in extreme, simplistic and divisive ways: There were lots of exaggerations if not outright lies, quite a bit of sensationalism.

(At the end of this blog I’ve detailed a few of the most egregious errors.)

The film chronicles about a quarter of the annual wildebeest migration cycle and presents it as seriously threatened by over zealous tourism and human development.

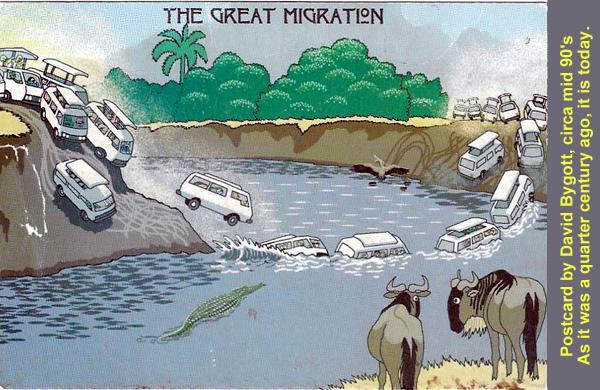

The over-zealous tourism is the mayhem which I detest yet have often contributed to, as crowds of tourists vie for position along the banks of the Mara River to witness a large herd river crossing.

The film (rather over zealously itself) claims that the wilde are “often” forced to cross in more dangerous places because of the crowd of vehicles waiting for them at “their normal crossing points,” which then manifests in unnecessary injuries and a greater potential for predation by the crocs.

Yes I’ve seen that happen… too many times. But there are also plenty of us responsible guides who clear out of the drive-in theater crowd, pull back and watch from further afar. That’s not easy to do: The cost of a safari today is crazily expensive.

Truly, more detrimental to the migration than this juvenile tourist behavior is the problem of human development. While the film discusses this it falls far short of giving it equal time or with any parity of the emotion expressed showing the crowds vying for position at a crossing.

The greatest disappointment is PBS’s simplistic attitude to this enormous problem.

The documentary presents this intricate, complex human/wildlife conflict like a fairy tale: Create private conservancies so attractive by their size and restrictions that the wildebeest will just shove the tourists aside and flee to their new-found paradises like Gretel pushing the witch into the oven.

It’s not going to happen. It hasn’t happened, and it’s been tried for years. At least I’m glad they no longer call it ecotourism.

I’ve written extensively on the manifest failures of ecotourism and there’s no better example than the dynamics of the Serengeti/Mara ecosytem. And nothing is changed from the failures of ecotourism by calling it “private conservancies.”

Kenya’s Maasai Mara reserve is extremely tiny when compared to other popular African protected wildernesses. A generous reading of the three independent sub-conservancies that form the national reserve suggests an area of about 500 sq. miles, a rectangle roughly 25-30 miles long and 15-18 miles wide.

Tanzania’s Serengeti or South Africa’s Kruger national parks are each 9 to 10 times larger. Botswana’s Chobe is 9 times larger and Zambia’s South Luangwa is 7 times larger.

Yet the Mara is king and always has been. Even when I started nearly a half century ago the density of tourists in the Mara was greater than perhaps anywhere else but Kruger. And in the ensuing years the Mara has developed so rapidly that it’s now far more congested than Kruger.

And there’s good reason for all this. It’s one of the most beautiful places on earth. Its unique ecology manages a prairie grassland that gets almost as much rain as a jungle. So its regenerative potential is far greater than the more normal wildernesses of sub-Saharan Africa, which historically suffer from extreme seasonal fluctuations.

And so it brings in and sustains an animal population that many conservationists have always argued is way beyond balanced capacity. And just as this unique ecology draws animals and tourists, it draws ranchers and farmers. The ecology radiates especially north and east of the Mara with some of the finest ranch land on earth.

Over time these two parallel conflicts have outpaced and out performed every solution tried… including private conservancies.

So the film is dangerously – I’d almost say morally wrong when suggesting we know of a viable solution. It sourly neglected the recent protests of various groups, from taxi cab drivers to ranchers, over government promoted conservancy policies.

Fact is that ranching and other forms of agriculture are rapidly producing more revenue than private conservancies could ever hope to generate, and this is something we’ve known for a very long time.

It’s all about money. Which is really about health and comfort, which is about food and shelter.

So we’re left with little hope but that the revenue and jobs from national tourism – quite apart from the small contribution of private conservancies – can some day be competitive with but without threatening modern agriculture.

Covid really clouded ongoing analyses of the future of such tourism, and of the best policies for such components as park fees. But just before Covid all we could say is that… it remains to be seen.

If tourism is successful as a solution, it will do so in large part because of vehicles jostling for position at a wilde river crossing in the Mara.

I don’t like it; but them’s the facts.

* * *

Piqued Picks

Sensationalism: “This relatively short leg of their journey is especially fraught with danger.” The northern part of the migration including river crossings actually results in fewer wildebeest deaths than in other parts of the cycle. The greatest herd attrition occurs during calving as predators patrol the herds. The second greatest attrition occurs before the herds get to the Mara and after they leave it, on difficult treks that in fact cross several more rivers in Tanzania.

Several times the film casually referred to the wildebeest numbers as decreasing. There’s no evidence whatever for this. In fact the most recent counts, which were interrupted by Covid and lacked the scientific regimen I would have liked, suggest just the reverse. It’s probably true that fewer and fewer are going into the Mara. Wetter conditions from climate change means that the grasses further south in the Serengeti grow for longer periods so the wilde don’t have to always move into the Mara. Overall, herd numbers are likely increasing.

The film quotes one of the Maasai guides as complaining that there is too much rain and that’s why the wildebeest stay in Tanzania. Right on, guy. But the film depicts this as a problem. It isn’t at all. It’s wildlife adapting to climate change.

Gazelles don’t migrate, despite the film claiming they do. The film also claimed that eland migrate, which most don’t and even showed a clip of a “saved migratory animal” jumping up from a snare. The animal wasn’t a wildebeest. It was a non-migratory topi.

Perhaps the most egregious untruth pandered by the film was the inference that poaching is a Tanzanian, not a Kenyan problem, as Kenyan rangers on the border patrol for snares as if they were brought up from Tanzania. (Tanzanian rangers also patrol for snares, folks.) This is a bizarre reflection of a long running immature feud between Kenya and Tanzania that is the reason that the border separating the Mara from the Serengeti has been closed since 1979. In my view there’s more poaching on the Kenyan side, just because they have better technology there and a more efficient black market in bush meat.

The Loita Migration is a controversial notion. Many of us who have been around for so long see the Loita Migration as an aberration of the normal wildebeest cycle that reflects the human/wildlife conflict. It didn’t exist when I started my career and came into being as new roads, mostly, interrupted the regular oval migratory route. Similar situations have happened in Botswana and South Africa.

Great dissection of so called facts presented in a excellent cinematography production. But once again thanks to Jim seasoned veteran for the last 40-45 years or so doing corrections as needed. Is there anybody better than the answer man. It’s been a pleasure traveling knowing traveling and hanging with Heck in Africa but mainly the Serengeti over the last 28nyears. Thanks again EWT