I just returned after nearly two months (on separate trips) into Botswana, and I’ve watched with trepidation albeit excitement a natural event which has not been recorded before. The Okavango Delta, one of Botswana’s most important tourist attractions and one of the most unique ecosystems on earth, is going bananas.

It isn’t a surprise. This is the third year running that the Delta has reached dangerous levels but the latest predictions made in mid-April suggest this year will be the worst ever and that it will continue to get worse and worse in the years to come.

This is extremely dangerous mostly to the fragile human populations eking an existence on the trail of water leading back to the Angolan Highlands, where it all originates.

But dangerous as well to the serious investments many have made in Botswana’s tourism industry.

And dangerous or at the least very disrupting to tourists. My account on this is first-person.

First, some necessary background:

The Okavango Delta is essentially the Kalahari Desert flooded. Excuse the non sequiturs, but it’s not my fault, it’s the vernacular that called central Botswana a desert. The Kalahari isn’t really a desert. It gets more rain per year than much of America’s southwest. It’s a Mojave plains, or high sierra butte that doesn’t get a lot of rain, but lots more than a desert.

But unlike the Mohave or high sierra, its ground base is grey-white powdery sand, the result of millennia of flatness and repeated rapid evaporation in a severe climate where summer temperatures can exceed 110F and winter temperatures can sink below freezing.

This has led to an extraordinary unique ecosystem, with plants fantastically adapted to grabbing and conserving the rain that does fall.

And every year unbelievable amounts of water spill into its upper regions. And as global warming melts the ice caps, there’s more and more water. Where the water spills onto the Kalahari is the Okavango Delta.

The Delta doesn’t dry up when the surge of water coming out of the Angolan Highlands ebbs as it does every year with the end of the Angolan Rains. The effect of millennia has been cumulative. At all times of the year there is a marshy, swampy, river run Delta. It has grown or receded over the centuries but it always bloats the first half of the year and shrinks back a little the second half of the year.

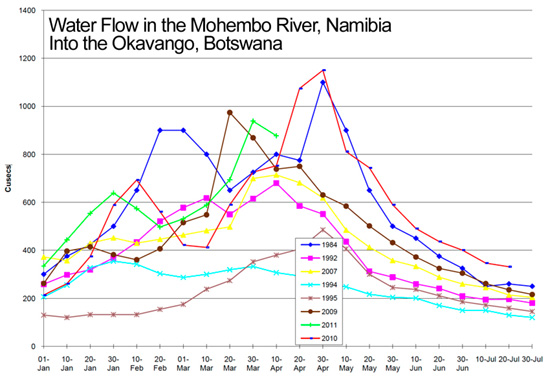

The UN Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs (OCHA) issued the latest comprehensive scientific report several months ago, and the more recent and detailed graph below is now in circulation.

All indications point to worse years in the future.

The bottom line is that many of the camps, campsites and tourist lodges in the Delta may be in peril this year.

In early March I visited the northeast Delta. The airstrip at Kwara camp was flooded. The managers made the mistake of trying to keep the camp open by transporting passengers 2½ hours from the next nearest workable airstrip.

But the tracks from that airstrip to the camp were also flooded. The vehicles flooded out. In one incident, water was above the floorboard as we stared a small crocodile in the eye.

A month later I visit Jao Camp in the southwest Delta. Twenty-four hour pumps and a three-foot high ring of sand bags around its airstrip barely kept it functional. I watched a Cessna 208 slip as it landed. The water lapped at my cabin deck and game drives were as if in partially submersible military vehicles.

Both these camps are operated by very good companies, and their experience is shared by virtually every camp in the Delta. It’s critically important these two camps not be singled out from the other 53 in the Delta that all face the same problem.

True “water camps” as Delta camps are locally known, are understandably positioned to experience the unique delta floods. It’s just that no one expected the ice cap to melt this quickly.

This is quite serious. Two of the three “pushes” or surges of flood waters that occur each year are over, but the third is yet to come. So even as the rainy season ends in southern Africa (usually right about now), the flooding of the Delta will continue. Last year waters did not begin receding until August.

I have great sympathy for Delta camp owners and investors. Kwara, in fact, has rebuilt both the airstrip and camp to higher ground.

But will it be high enough?