2012 demonstrated more than any other year that African countries are doing better economically and advancing faster socially than their counterparts in The West, their former colonial masters. Except, I’m afraid to say, the giant in the hut, South Africa.

My #3 Top Story of 2012 is the explosive narrative of African progress, and the #4 story is the significant exception, South Africa. To see a list of all The Top Ten, click here.

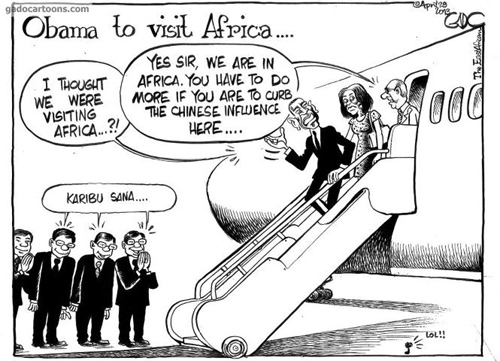

“Africa isn’t just a place for safaris or humanitarian aid. It’s also a place to make money,” says New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff. The well respected author then went on to site dozens of statistics showing Africa out pacing the world economically.

Clearly the average African is neither as comfortable or well off as the average American. But that’s not the point. The average African is mountains higher in comfort and well-being than his parents, and there is every indication that his children will share that euphoric experience.

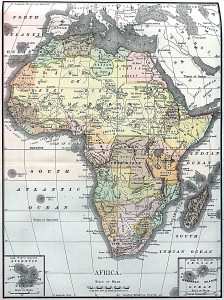

This is, of course, a generalization but I feel a fair one. Including Somaliland, there are 56 countries in Africa. Perpetual doom and gloom persists in Zimbabwe and the Central African Republic. Increasingly bad news in 2012 plagued Angola, Uganda, Rwanda, Chad and Mali. So my generalization applies to the rest.

This positive view stands in marked contrast to America, where the generation to generation comparison is dismal. The graph projected out another generation or two actually has parts of Africa catching up with American median income.

The World Bank explains this succinctly as a wealth of new natural resource discoveries. Like oil and gold.

But that’s hardly the end of the story. The new-found wealth in the ground is a necessary foundation, just as rich soil was to early Americans and oil was to the 1960s Arab in the Emirates.

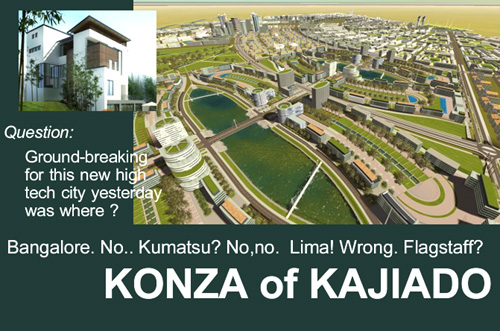

But on that foundation is blossoming some exciting non-natural discoveries, in high tech and alternative energy, in natural products manufacture and a score of other industries.

It was poorly reported but extraordinary this year that South Africa bailed out Europe. That’s right. South Africa paid $2 billion into a world monetary fund to help with the Greek and other European bailouts. Economically, the First World took charity from the Third World.

And Africa has no qualms about embracing the best of capitalism, thank you. Walmart was welcomed into South Africa with a warmer embrace than most mid-sized towns in the United States provide the retailer.

But after the hugs and kisses were over, Walmart submitted to a labor agreement that Americans working for Walmart would die for. Why are they able to do this in Africa, and not in America?

And “thing development” is progressing no less fast than social and “thought development.”

Consider the media, (I am). A respected global media watchdog claims that Tanzania has a freer and better media than the U.S. This is because of the worst of American media, which pulls down the overall ranking.

But the worst of American media, Fox News, Rush Limbaugh and sorts, have made mincemeat of the truth, have thrown civility to the wolves and turned making money into a first principal that cares little about the effects of its nearly sadistic approach to the public need.

In defense some of us Americans would point to many exceptional online services like Wired and Mother Jones and The Nation (and dozens more), and as you examine those “good” media you’ll find out the reason is the same as for Tanzania’s position: youth.

America is aging less than gracefully and its right-winger lying mentality is very much linked to old guys. So perhaps Africa has an intrinsic advantage, since such a large portion of its population is young relative to America’s.

Yesterday was historic for the American Congress: 78 women in The House and 20 women in the Senate. This reverses a trend begun about a decade ago where women in elected office began to decline.

But in Kenya that would be mandated at 145 in The House and 33 in the Senate! Mandated?! Yes, Kenya’s new constitution requires that a third of all elected officials be women, almost doubling in one fell swoop what it’s taken America more than 200 years to accomplish.

The new Kenyan constitution, modeled but improved on South Africa’s new constitution, is quickly becoming a model worldwide. Simple and common sense things like religion banned from schools and institutionalized affirmative action that adjusts to ethnicity and gender as society continually changes puts Kenya on a markedly higher moral plane than America.

I think above all other things socially, though, is the new African attitude towards justice. America is petrified with the concept of sharia Law, for instance if applied in the new Egypt. But Americans understand little of this and can’t even see how any set of laws can be molded to virtually any social model.

Our own Supreme Court has bent and twisted, upheld and struck down, and essentially remolded and unmolded society again and again. American laws on such things as drug possession (marijuana), abortion, gambling and even incest and slavery have gone all over the chart!

There was no direction from the “Founding Fathers” on those issues part and parcel to modern day life. And the irony is that so many Americans think otherwise, that there is some Founding Father out there guiding our every move.

The new Kenya justice will be an amalgam of Islamic sharia and British common law. Some feat, eh? But beautiful and adjusted to the realities of its new society.

But Kenya recognizes – like so much of the world, America excepted – that there is a global morality, today. That there is a worldwide foundation for such things as basic human rights.

Four of Kenya’s most prominent citizens have submitted to charges filed against them at the World Court in The Hague. Voluntarily they will go to The Netherlands for their trial. Now it needs to be said, of course, that these criminals (as I think they are rightly charged) would likely not do so if the Kenyan public hadn’t forced them to. And that is the majesty and beauty of the situation.

An important aside: recently convicted in the World Court, former Liberian leader Charles Taylor in pleading for leniency in his sentencing for war crimes pointed out that he was convicted of crimes no different from those of George Bush in Iraq.

The justices gave no reply.

This was not the case for our own great Justice Ginsberg who dared to speak the truth in Cairo, when she told the Egyptians that maybe the U.S. constitution wasn’t right for them.

The onslaught of criticism that followed, the incredible vitriol from the right, wasn’t just humiliating to us Americans, it was … well, barbaric. It was truly like German Goths grumbling over Roman progressives. Ginsberg is of course right, and fortunately she rather than Senator Kruz is what Egyptians will and are considering for their own new, progressive societies.

But alas, it’s not all good news for Africa. Africa’s behemoth is South Africa. Its economy is multiples of the rest of the entire continent combined. Its history is as complex and fascinating as our own. And hardly 20 years ago it reformed itself into one of the most progressive, moral societies on earth.

But now, things don’t look so good.

Residual racism and neo-apartheidism are sprouting across its non-black societies. I don’t think this is because it was always destined to be so, that there was some kind of intransigent ethic among whites that would eventually surface again, like an old whale on its last sound.

Rather, it’s because the current president has made it so. Jacob Zuma is a joke.

He’s vain, and easily set off by criticism. He’s so wrapped up in himself, he’s let the country wander leaderless. He’s patently ignored the courts, acted like a banana republic dictator and all the while the country spiraled downwards.

Many local experts, white and black and left and right, are beginning to see him not so much a central actor separate from the times, but rather the embodiment of something greater:

The implosion of the ANC, the freedom fighter party that won the battle against apartheid and whose marshal was Nelson Mandela.

I think this is true, and that’s why this is my fourth most important story of 2012. Yet it’s with hope that I also see Zuma coming to an end sooner than the constitution would mandate, and of the ANC moving restlessly to get its act together. It may, however, be too late.

So the year ends on an incredibly positive note for the continent as a whole, but a seriously cautionary one for its grand marshal.

What’s going on in Nigeria is Art: The Art of Life in a mega-city after the village. The Art of Survival in the age of Snowden. It’s a mega-mess, beautiful and getting better. By most accounts there’s less of a chance you’ll get killed, now, but if you do it’s likely your coffin will be fusia colored.

What’s going on in Nigeria is Art: The Art of Life in a mega-city after the village. The Art of Survival in the age of Snowden. It’s a mega-mess, beautiful and getting better. By most accounts there’s less of a chance you’ll get killed, now, but if you do it’s likely your coffin will be fusia colored.

When Guernica magazine asked the LPF founder, Azu Nwagbogu, why he created a festival dedicated to photography, he replied, ”[That is] the fastest growing art tool on the continent, and it’s perhaps the easiest to gain access to.”

When Guernica magazine asked the LPF founder, Azu Nwagbogu, why he created a festival dedicated to photography, he replied, ”[That is] the fastest growing art tool on the continent, and it’s perhaps the easiest to gain access to.”