The Obama Administration may have hastened rhino extinction in order to achieve political capital in Wisconsin.

The Obama Administration may have hastened rhino extinction in order to achieve political capital in Wisconsin.

Charity begins at home, and there’s no more powerful example of this than for Americans interested in saving rhinos and no greater reversal in my life time than what the Obama Administration has just done.

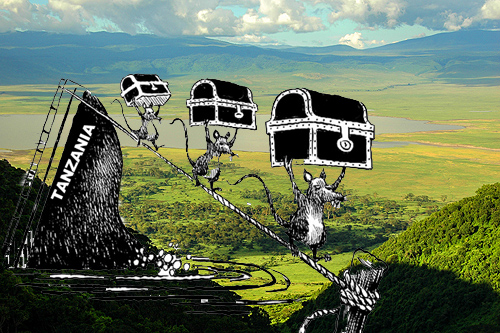

For the first time since U.S. laws then international treaties prohibited international commerce of rhino, the Obama Administration has issued a waiver to David Reinke, a big-game hunter from Wisconsin allowing him to import the rhino he shot in Namibia in 2009.

This is the first ever waiver issued by any administration since America’s Endangered Species Act became law in 1973, and may in fact put America in violation of the world-wide CITES treaty of which America was so instrumental in creating.

The action by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has raised numerous eyebrows and not only among wildlife advocates, and occurred right when the European Union enacted even tougher bans on the trade of rhino within EU country borders.

Fish & Wildlife’s explanation is pitiful. It invokes a moral platitude that sport hunting can support conservation, which while sometimes true is absolutely not in the case of any endangered species. And it cites as a positive reason for issuing the waiver the more than quarter million dollars Reinke spent on his rhino hunt in Namibia.

To many of us, this action is patently political: Trade rhino for political capital in the contentious arena of Wisconsin by wooing over a major Republican supporter. This time I’m not only joined by the Huffington Post that suggests as much. So does Scientific American.

Tuesday’s blog about the American Wade Steffen and today’s blog about the American David Reinke and the Obama Administration illustrate how misplaced American support for saving the rhino may be.

Every single save-the-rhino (or save-the-elephant, or save-the-groundhog) group on earth presumes, and correctly so, that commerce of any kind in that animal increases exponentially its black market thereby massively increasing the threat of its extinction.

If Fish & Wildlife argues that Reinke’s quarter million dollars will save the rhino, why not just issue hundreds of waivers each for a quarter million dollars? Or thousands of waivers?

It’s a child’s tease while the Obama Administration plays god with politics. Once a single international transaction of commerce has occurred — as it now has — subsequent transactions become easier and easier.

As my own experience in Africa developed over the years, “charity begins at home” grew increasingly important to me, but in an usually straight-forward manner: Yes, there’s horrible poverty in Africa, but there’s also horrible poverty in America.

What’s worse is that poverty in Africa is declining; poverty in America is growing. I’m an American, not an African. Ought whatever talents or skills I have to mitigate poverty be directed first at home?

But what about saving big-game wilderness, a concern much more African than American?

You have your answer in this blog and my last one, “Dumb Roper Nabbed.”

It doesn’t matter how much money you’ve sent to rhino-saving charities, or how much time or other resources your zoo or conservation society has allocated to rhino protection, your political leader has just reversed much of what you thought you were doing.

Charity begins at home.