Invisible fences for pet dogs are common in the U.S., but they’re used with opposite purpose in Africa: to keep the unwanted out.

Invisible fences for pet dogs are common in the U.S., but they’re used with opposite purpose in Africa: to keep the unwanted out.

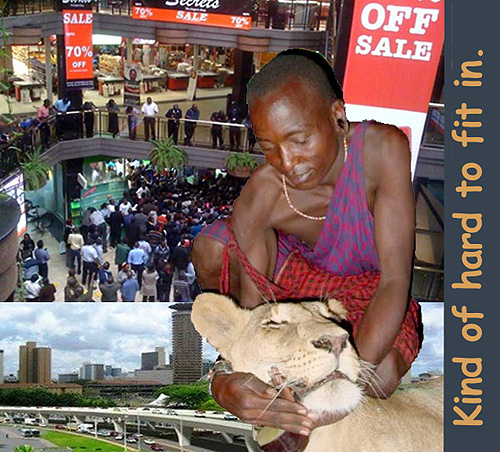

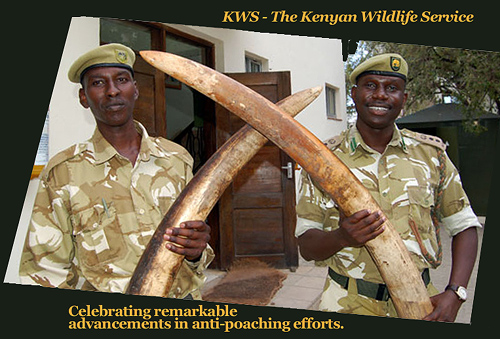

Africa’s big game parks are mostly huge tracts of uninhabited wilderness but increasingly sophisticated agriculture and ranching impinges on many of the borders. There is the obvious social/political human/animal paradigm to work out, and it is becoming contentious.

But to the extent the wild game parks are to be preserved, there’s always been an easy, inexpensive way to demarcate Africa’s national reserves and make them nearly impenetrable by outsiders.

These “invisible fences” are not manufactured like an American dog collar, although they’re often easily manipulated, and they have kept nicely divided wild animals from domestic stock and farmers for generations.

The best known of these is the tsetse fly. Tsetse no longer transmit human sleeping sickness but they continue to carry bovine sleeping sickness. Wild animals are immune to it; cows, sheep, goats and horses aren’t.

(Recent genetic research identified the specific gene that makes domestic stock susceptible to tsetse, but Africa is a long way from creating a practical therapy for domestic stock based on this.)

Tsetse must carry a kamikaze gene, because they’re easily fooled into killing themselves. Simple fabric traps of alternating blue and black, and sometimes white added, layered with pesticide is a certain end to tsetse wherever the trap is laid.

Strategically placing these traps produces an invisible fence. Lodges, camps and ranger stations in wild areas mark their perimeter this way, becoming tsetse free.

In fact tsetse could easily be eradicated completely this way, but park authorities don’t want to do this. That would also eradicate the invisible fence.

Hoof-and-mouth disease, as well as anthrax, are incomplete natural fences. Wild animals do succumb to them, but not as readily as domestic stock.

That was why Botswana authorities in the 1980s began erecting elaborate electric fences and moats to separate the wild from domestic lands. The project is considered successful since it safeguards Botswana very important cattle industry. But it does so at the expense of about a third of its wild animal population.

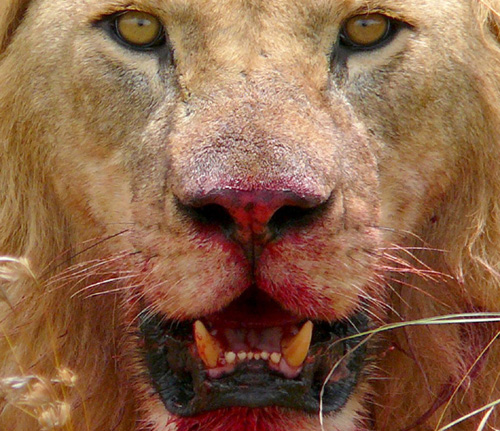

But until now there was one other disease that was a certain invisible fence between many of Africa’s great herbivores like wildebeest and domestic stock: a virus known as the “Malignant Catarrhal Fever Virus” (MCF).

This herpes-type MCF is a world-wide virus of significant concern to ranchers, and it’s been long studied. The developed world learned that sheep carry the disease very much like wildebeest without easily succumbing to it, but that sheep readily transmit the disease to cows, which then fall quickly.

So strategies for dividing sheep from cows employed aggressively in the 1950s led throughout the developed world to a managed situation where MCF wasn’t eradicated but didn’t cause a lot of trouble.

But it’s different, today, in Africa. The wildebeest population is rife with MCF. In fact nearly every female wildebeest tested carries it. There are many ways the disease can spread, including a slight risk through airborne transmission, but the principal way seems to be when the female wildebeest calves.

The birthing fluid lost in calving is saturated with the virus. When the herd moves on, the ground retains the virus for a very long time. There is even a suggestion that new grass which subsequently grows in the area contains the virus.

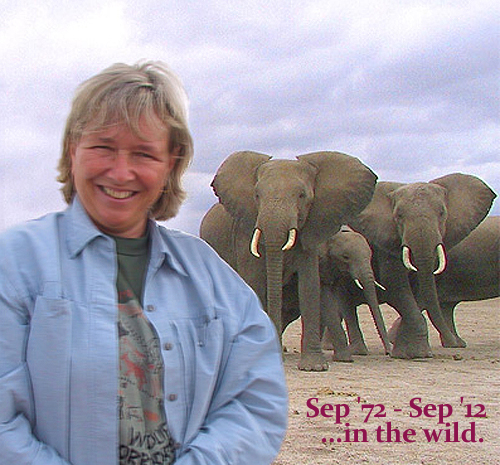

In the old days, when there was less developed agriculture in Tanzania, ranchers “would migrate with their livestock elsewhere because there was still ample land, but now there is nowhere to go,” Dr. Moses ole Nasselle told the Tanzania Daily News this week.

Ole Nasselle leads a team of professionals in the Serengeti ecosystem that announced Monday they had produced a vaccine against MCF.

The competition for land is intense in Africa. One of those playing fields is the continent’s great national parkland.

This week, advantage ranchers.