If you want to dispose of Grandma’s necklace, you better do it before August.

If you want to dispose of Grandma’s necklace, you better do it before August.

Last week Fish & Wildlife inched towards final new August regulations on the sale and use of ivory within the U.S. Orchestras were elated, piano vendors were piqued, and the Wall Street Journal was furious.

The Thursday announcement is based on agency findings made the previous month but only published last week.

The Thursday announcement relaxed previously proposed regulations that would have prevented any musical instrument composed of endangered animal products (like ivory piano keys) to be brought into or taken out of the U.S.

At the same time, though, the agency reenforced proposed regulations that will prevent any individual owner of ivory less than a hundred years old from selling or trading it, unless of course if it is part of a musical instrument.

Other petitioners, like museums seeking the ability to produce exhibitions that include foreign works of art (like ivory that are not musical instruments), were not addressed.

In claiming victory for its lobbying, The League of America Orchestras said the adjustment was “in response to urgent appeals from the League.”

At the same time the revised proposed regulations tightened restrictions on the commercial sale of pianos with ivory keys.

“These regulations … place a burden on the piano industry,” a leading blog contended.

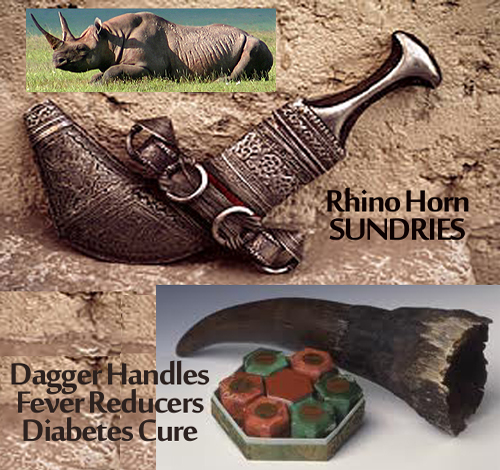

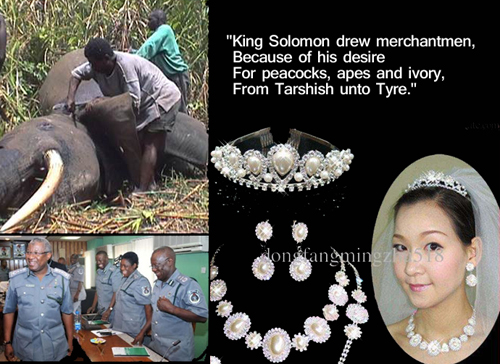

And it might be time to quickly sell your grandma’s ivory on eBay. If current regulations hold to August when officially implemented, individual owners of ivory less than a century old will not be able to trade or sell their products.

This effects personal ownership of jewelry, for example, and would restrict an estate from liquidating such ivory items in probate. It would also forbid any commercial transactions, such as selling Grandma’s “newer” ivory necklaces on eBay.

The agency has yet to specify, though, how an old piece of ivory can be certified to be more than a hundred years old, and it’s very likely that most individual owners of old ivory will not have adequate documentation to be certified.

This infuriated the increasingly irrational Wall Street Journal which somehow bundled into its ire Botswana’s ban on hunting as well, concluding that these two actions will hasten elephant extinction.

In sum it looks like the August regulations will be pretty tough, stiffing capitalists (Grandma) while ameliorating socialists (community orchestras).

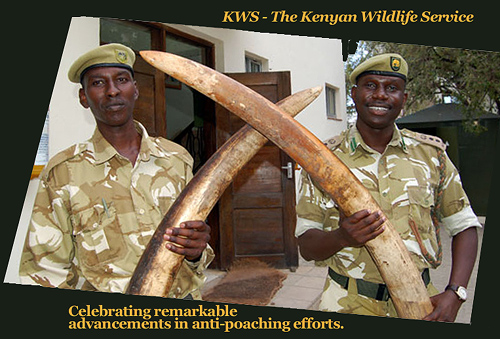

I like this attitude, but I remain skeptical that it will help solve the “elephant problem.” I worry that the increasingly complex regulations further American political interests while distracting real conservationists from the problem that there are too many elephants in our increasingly developed world.

If I’m right and this tedious and laborious march to August regulations is mostly political if a tad ideological, it’s not so bad in an era of center ring political fighting. But don’t forget that Obama had no qualms about issuing the only waiver ever for a Wisconsin politician to kill and import an endangered rhino.

Extracted from the bare knuckles of American politics, I wish Americans would focus more on the real problem: what to do about a contentious elephant population in a world where there are too many elephants.

Real and profound questions like should elephants be culled or poachers executed are much more important than whether Emily sells Grandma’s necklace.