Our fantastic morning in the crater demonstrated what crazy and simplistic ideas are propagated by entertainment media about wild animals.

Our fantastic morning in the crater demonstrated what crazy and simplistic ideas are propagated by entertainment media about wild animals.

Many of you probably think that every time a lion wakes up and takes a stroll he comes back with a wildebeest in his mouth.

Wrong. His success ratio of course varies from place to place but essentially is around 1/6, and often worse in stressed environments. Lions die of starvation as much as disease.

Hyaena was our demonstration animal, today, and what an experience!

There’s no question in my mind that the hyaena is the most dangerous predator. I believe this because of their maddening persistence and herding instincts which transform them from a scavenger into a vicious hunter.

Predators are mostly opportunistic, but even so it’s possible to dissuade a lion from bothering your abandoned calve by screams and stones. Not so for the hyaena committed to the chase. It will kill or be killed before abandoning its prey.

Only the prey itself can stop it: by running, by fighting or outwitting it, which is so much easier than a television special normally suggests.

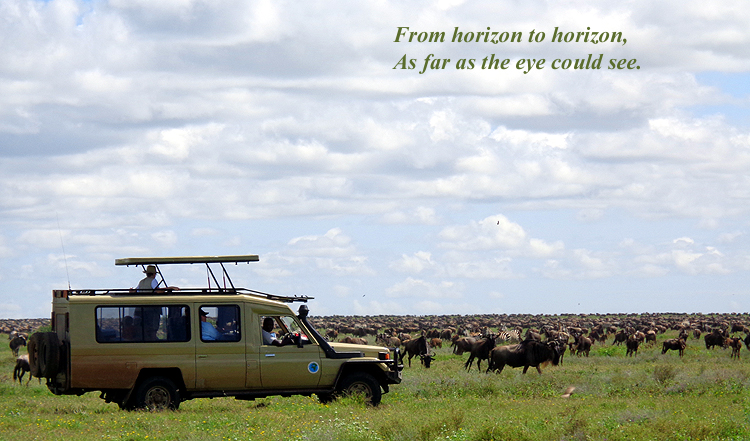

We were looking at a line of buffalo in the far distance early this morning in the crater. It was our first great sight of the morning after getting to the floor shortly after dawn.

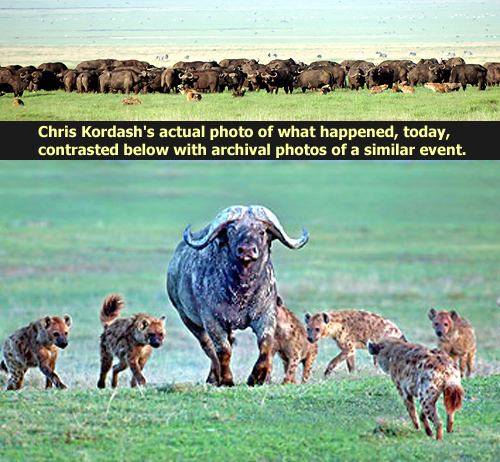

Then I saw more than just the line of about 50 buffalo, one of the Big Five and usually considered the most dangerous prey by man, the hunter. About two dozen hyaena were racing back and forth along the line, tails buffed and held high, their whooping becoming laughing. This was incredibly puzzling and surprising.

The hyaena were clearly in kill mode, but buffalo as their prey? One buffalo can weigh 4,000 pounds and it’s almost all muscle and meanness. I’ve seen a 350-pound wildebeest thrown to the sky by the powerful rack of a male buff.

So what was going on?

More and more hyaena came racing to the “battle” if that’s what it was, and the buffalo lagered. The big males came to the front and stood side by side swinging their racks as if clearing the land.

But the hyaena continued and soon we could see some of the crazed and furry beasts racing around the end of the line to the other side of the buffalo. Although we couldn’t see exactly what was happening on the backside, we could tell by the buff’s agitation that the battle was truly engaged.

Then the buff family began to run with dozens of hyaena in pursuit on all sides of the herd.

We raced our cars around some roads to try to get a better view, but the buffalo had been dispersed by the hyaena and we couldn’t see the outcome. Then about 20 hyaena came running over a ridge to the side of us quite near the car, and we raced with them down the veld wondering what was going on.

Then their whooping slowed and their tails unbuffed and they start to walk and wander like hyaena normally do.

We followed them best we could on roads and with our binocs and from time to time they reorganized and molested herds of zebra and wildebeest and soon it seemed like the whole western side of the crater was in turmoil with animals running everywhere.

And just when we thought everything had calmed down, nearly 90 minutes after it all started, we saw a single lone buff running from a line of hyaena.

His chest was bloodied. His left leg was seriously injured, but he managed to outrun or outwit or both the hyaena and after disappearing behind a ridge, the pack stopped their attack.

I’m not sure how many “packs” we probably saw, but the whole crater was churning with hyaena kill.

Yet we couldn’t see one successful take-down.

Hawana mipango is the Swahili expression we attached to these seemingly failing killers: “no plans” and that exactly describes what we saw: incredible killers having organized their power but unable to effect success because their attacks are so reactive, unplanned.

The crater calmed down and we headed to lunch. In a dip near the only spring-fed lake in the crater, a beautiful location with a few hippo and high lustrous elephant grass, we saw the old buff that had been attacked.

Alone and dying. He was bleeding to death and so weak that his left leg was gnarled under his body in a horrible position. He would die. And there were no hyaena anywhere near him to claim the prize.

That’s truly the wild: heartless to be sure, but almost amateurish; random possibly and nothing but opportunistic. From time to time the coincidences in the wild converge and there is a kill.

But more likely, there isn’t. Just another day, another hour, for another opportunity. Survival, after all, is what keeps us all going, and that’s been much more successful in our legendary history than defeat.

We didn’t “do” the Cape Point like most people “do it.”

We didn’t “do” the Cape Point like most people “do it.”  Together with our 74-year old guide, John James from Fishoek, we decided to hike from the southwestern most point on the continent, to the visitor’s center where the funicular is.

Together with our 74-year old guide, John James from Fishoek, we decided to hike from the southwestern most point on the continent, to the visitor’s center where the funicular is. It was a most invigorating day.

It was a most invigorating day.