The loss of wilderness critically impacts our lives. African compromises known as “same species intervention” and “protected wilderness” may be bitter sweet solutions.

The loss of wilderness critically impacts our lives. African compromises known as “same species intervention” and “protected wilderness” may be bitter sweet solutions.

I just returned from a visit to the Amazon where I saw first hand the destruction of the planet’s jungles, the transformation of its rivers into commercial pathways for man’s insatiable consumables, and the slaughter of its wildlife.

But as sad as this is to see, it’s nothing new. I’ve watched it happen my whole life in Africa.

The human/wildlife conflict is well known and less contentious, really, than simply troubling. When a decision must be made to choose between man or wildlife, or between man’s survival or the destruction of the wilderness, there’s no question in my mind that man must prevail.

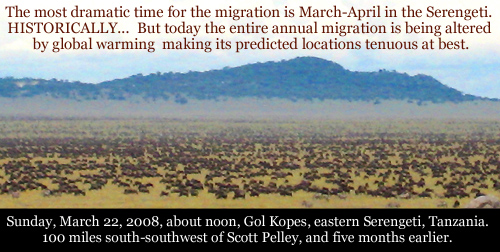

Many have argued that conflict doesn’t exist: that man and the wild are never completely at odds with one another, that both can be preserved. But I think that’s either nonsense or simply employing impractical logic. We cannot reverse quickly enough our use of fossil fuels, our need to eradicate poverty, or our endless warring ways, to abate the destruction of the wild in any macro economic way.

More reasoned intellects argue that we are essentially crippling ourselves each time we cripple the wilderness. And there is powerful evidence to support this, not least of which are the many organic drugs discovered in the natural wild. But this becomes an odds game. What are the chances we’ll find another cancer drug in the Amazon before Rio’s favelas either waste away in cholera or typhoid or explode in revolution?

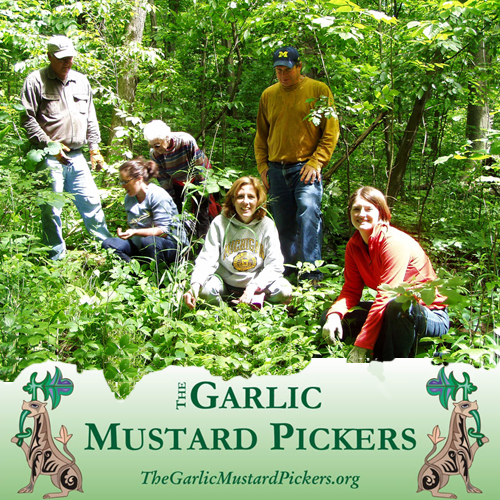

And the finally there’s that ludicrous notion that we can make wild, wild. Pull out that garlic mustard plant, John, and save the wilderness from itself!

What we don’t get is that the wild nature of the wilderness, its own ability to decide what to do with itself, is critical to the very nature of man; after all, we are an organic beast. If we disown the wild by claiming we know better than its intrinsic self how to preserve itself, we disown part of our own essence. Is that necessary?

It’s taking an enormous risk. We’re gambling that we don’t need to know the things of the wild that for the moment remain its mysteries. Pluck that garlic mustard and who knows what else you’re plucking from existence!

I think Africa may be providing a couple compromises. They aren’t holistic solutions, but it may be the best we can do.

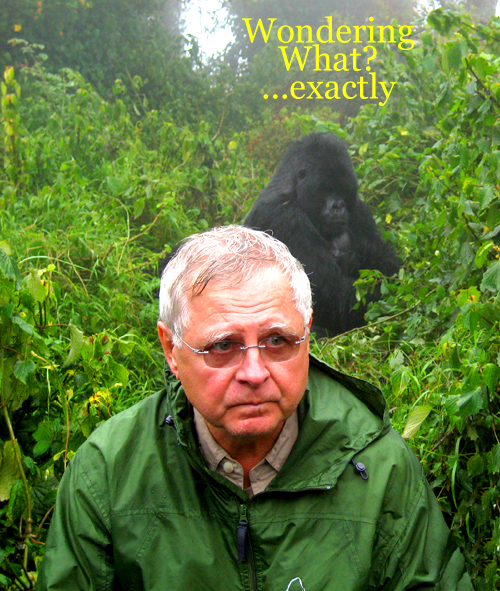

Yesterday “Gorilla Doctors” treated a festering wound of a silverback who had been in a fight with another male. They did this by darting the animal with a powerful antibiotic.

The group also reported a rather quiet start to June, with “few interventions” that nonetheless included anti-biotic treatments of juveniles and darts of anti-inflammatory drugs to relieve pain.

Gorilla Doctors is a new phenomena in my life time. I remember in the mid 1980s when scientists argued for months over whether to intervene in two crisis situations in the wildernesses of east and central Africa.

The first involved the mountain gorillas. One of the animals was identified as suffering from measles. The only possible way that could have happened is that a tourist had transmitted it to them. The question was, do we use the simple and available medicines we have available to cure the disease, or do we let the baby gorilla die?

There were two compelling arguments to treat the baby gorilla. The first was that man himself had upset the balance of the wild, since it was man that introduced the disease. The second was that the disease had an epidemic potential. If not treated, the entire population was at a greater risk of extinction.

The decision to intervene is not reversible. It sets the stage for an uncommon relationship between man and the wild he wants to protect. Once the vaccine was used, every baby gorilla that was subsequently born would have to be vaccinated. Just like humans. And that’s exactly what’s happened.

Not too long thereafter, mange raced through the population of cheetah living on the East African plains. This beautiful cat is highly inbred, which means that throughout its wild population any disease can be devastating. Mange is ridiculously easy to cure. Just puff a bit of antibiotic powder pretty randomly over some part of the animal near an orifice and poof, cured.

And that’s what was done.

Since these first two breakthrough interventions in the wild, intervention has developed exponentially. And the justifications for them have become less and less simple. Successful vaccinations of pet and feral dog populations on the periphery of wild dog populations proved successful in increasing wild dog populations. But now, it appears the wild dogs must be vaccinated, too.

Each one of these interventions alters something that was wild into something less so, but ensures the preservation of that alteration with much greater certainty than its original wild form. We call this “same species intervention.”

This stands in marked contrast to plucking garlic mustard from county preserves. Same species intervention attempts to preserve a life form (mountain gorillas, cheetah) without altering the biomass around it. The second presumes to prevent destruction of other life forms by eliminating the first (garlic mustard for who knows what).

I find the first strategy tolerable; the second not. Both strategies tamper with the mysteries of the wild, but the second strategy tampers with too many mysteries, it exceeds the threshold of destroying one thing for another.

But these examples of deciding how to preserve life forms are only a part of the story. In fact, perhaps the smaller part.

Human/wildlife conflict is more pronounced than ever. It comes as no surprise but our preparation for its arrival was negligent. Elephants destroying farms, schools, threatening bicyclists and cars; lions worse than coyotes or wolves for taking down farm stock; Asian carp or zebra mussels screwing up our sewage systems much less redactional fishing!

Fences.

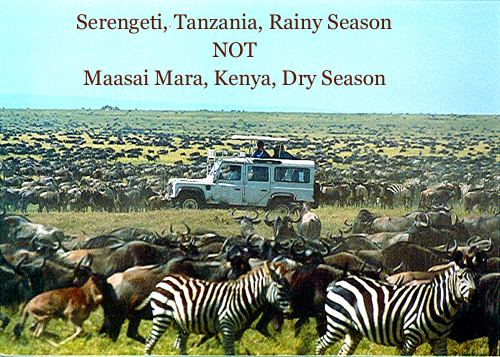

Africa is fencing all its wilderness. It began years ago with such mammoth projects as the 22,000 sq. mile Etosha National Park in Namibia, or the legendary Kruger National Park in South Africa (where part of the fence has now been removed, by the way).

More recently and at great local expense, Kenya’s huge Aberdare National Park was completely fenced. There are now calls for Kenya’s best park, the Maasai Mara, to be fenced.

“Fence” is a loose term. It could be moats or other types of semi-natural divisions that nevertheless bind the wild in specific containers we can try to preserve from man’s ruthless development.

Putting a boundary on the wild makes it wild no longer. The dynamic system becomes contained. The chaos and mystery of being undefined and unknown ends.

There are many spiritualist’s who believe this is doomsday:

“We perfect perfection to the point of

complete destruction.

And in the end, we will lose it all

as the weeds grow over our fallen creations

and the wonder of the wilderness returns.”

This final paragraph of Lisa Wields’ poem, “

Loss of Wilderness Means Loss of Self,” believes this tact will not prevail.

Unfortunately for the past but inevitably compromised for the only possible future… I believe it will.

Tanzania’s scandals and sheer wastefulness of its bountiful natural resources are legendary. But last month’s incident took the prize.

Tanzania’s scandals and sheer wastefulness of its bountiful natural resources are legendary. But last month’s incident took the prize.