The “unlawful and forced eviction” of up to 70,000 Maasai in northeast Tanzania has turned bloody violent. According to Canada’s Globe & Mail an initial tear-gas episode in early June has escalated into outright warfare resulting in deaths and injuries.

The “unlawful and forced eviction” of up to 70,000 Maasai in northeast Tanzania has turned bloody violent. According to Canada’s Globe & Mail an initial tear-gas episode in early June has escalated into outright warfare resulting in deaths and injuries.

“Shocking in its scale and brutality” this tragic situation is hardly new: Maasai have been driven from their pastures almost continually since their ancestors fled the Nubians in the 4th century BC. This complex story is one of the lectures I give on safari atop the Serengeti ‘Singing Rock’ that overlooks what was once the paradise of the Maasai before they ceded it to the government a half century ago.

The current conflict has its contemporary roots in a relocation of about 4,000 Maasai from northeast Tanzania in the 1960s right before Independence. A generation later in 1992 Maasai leaders formally accepted the government annexation of about 1600 sq. miles of their prime pastures which until then had remained an unresolved ownership issue with the British colonial government.

It remains uncertain whether the Maasai elders who ceded this huge area (the entire “Loliondo” district) understood exactly what they were doing or whether there was a lot of sugar spilled into the chai.

The area borders Kenya’s famous’ Maasai Mara to the north and Tanzania’s famous Serengeti to the west. These truly spectacular quintessential rolling grassland savannahs are perfect for cattle grazing, the traditional lifeway of Maasai.

Following the 1992 “treaty” the Tanzanian government quickly formalized smaller portions of that 1600 sq. miles as hunting reserves for Arab royalty. They had regularly hunted the area during their own insufferable summers ever since first being invited down by the British long, long ago for who knows what nefarious reasons.

After sectioning out hunting reserves for the Arabs who to this day claim they were given the whole of Loliondo by the British, the government declared the remainder “Wildlife Management Areas” (WMAs).

WMAs were and remain (intentionally?) so confusing that everybody and their brother ran up to this beautiful, game rich area to plant their own kind of stake. Including a group I was involved with for seven years.

In the early 2000s I had an interest in a company that had a remote wilderness camp close to where the Arabs were hunting. The mostly Jordanian militias that constantly harassed us claimed we were infringing on their area, but our WMA certificate had clearly delineated boundaries professionally surveyed for our 50,000 acres. Nevertheless, anyone coming into our “private reserve” would get a little beep on their cell phone, “Welcome to the Emirates!”

Ours was not the only non-hunting camp in the Loliondo area. By my last count in 2008 there were six. No one was ever able, however, to get a written document from either the Arabs or the Tanzanian government that would substantiate their claims to the entire Loliondo area.

I never got inside the Arab’s perimeter despite several attempts. Those who did reported “a little city” with an airport that routinely accepted the most modern private jet aircraft as well as C47’s that would disgorge limos and Range Rovers.

Maasai development was soaring by the end of the last century. Casual stock herding became true cattle ranching. In 1992 the price of a Maasai cow was around $70. Today it approaches $2000, a testament to Maasai’s rapid development and professional use of modern animal husbandry.

So more and more Maasai are choosing to “stay on the farm,” turning the tide that began in the 1980s when every promising young Maasai fled to the city. There are more and more cattle, more and more homesteads and guess what, no more land.

Disputes grew more violent after we left the area in 2008. Serious “wars” with Tanzania security forces occurred in 2009, 2013 and 2019.

I began blogging about this controversy in 2009. I ended that first blog by saying, “My take is that this is not going to get better, soon.”

The largest number of physical fights — not as deadly perhaps but much more acrimonious and self-destructive — have actually been between Kenyan and Tanzanian Maasai ranchers.

Originally, of course, there was no border splitting the Maasai into three countries (Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania). When the rain in the south was better, the Kenyan Maasai moved their cattle into Tanzania. And vice versa. So many more ranchers much better educated and lawyered up with many, many better cows are all fighting for the same number of blades of grass that grew here when the Maasai first arrived nearly 300 years ago.

In 2018 Tanzanian Maasai prevailed in the totally powerless East African Court of Justice which affirmed their historic rights to grazing throughout the area. This has sustained an increasingly articulate and powerful movement led by several courageous, young and very professional Maasai lawyers.

I think that Covid explains much of the current battle. No one came to Tanzania for nearly two years. Maasai in this area just naturally started grazing all over the place, including into the Serengeti National Park and the Arab hunting areas.

Covid’s over, the sheiks complained. Sheiks are rich and powerful. Maasai ranchers are not.

The piles of faulty treaties, questionable agreements and coerced submissions to informal modern use of deeply historical use, all compounded by an inept government that mistakenly tried to manage the area with incomprehensible regulations has just piled mess upon mess.

Untangling it is impossible. It’s time that the Tanzanian government emulate Canada with its First Nation policy or America with its modern Athabascan Alaskan policy and recognize the historical first principle of Maasai ownership of the lands and send the Arabs back in a heat wave.

Is that likely?

Haiwezakani sana…

Who cares that an elephant eats 150 pounds and not 250 pounds per day; or whether the peak of the dry season somewhere is October not September; or whether the start of a river is some unknown spring in the wilderness rather than a branch of hundreds of springs or rivers; or whether a huge part of Africa is independent or a part of Zambia?

Who cares that an elephant eats 150 pounds and not 250 pounds per day; or whether the peak of the dry season somewhere is October not September; or whether the start of a river is some unknown spring in the wilderness rather than a branch of hundreds of springs or rivers; or whether a huge part of Africa is independent or a part of Zambia? Beware The Woke. For half a century I’ve lived, worked and critiqued Africa. Now I’m supposed to relent, regret what I did? This mostly leftist campaign currently focused on the entertainment industry is ready to pounce on me and thousands like me.

Beware The Woke. For half a century I’ve lived, worked and critiqued Africa. Now I’m supposed to relent, regret what I did? This mostly leftist campaign currently focused on the entertainment industry is ready to pounce on me and thousands like me. Out there in the milky skies of a not-so-distant horizon I see the first sparkles of a mammoth explosion rising up from the yet slimy volcanoes just below ground: the travel bubble bursting.

Out there in the milky skies of a not-so-distant horizon I see the first sparkles of a mammoth explosion rising up from the yet slimy volcanoes just below ground: the travel bubble bursting. At last a very important film on the human/wildlife conflict!

At last a very important film on the human/wildlife conflict!  “Our interaction with Britain has been one of pain, death and dispossession, and of the dehumanisation of the African people. We do not mourn the death of Elizabeth.”

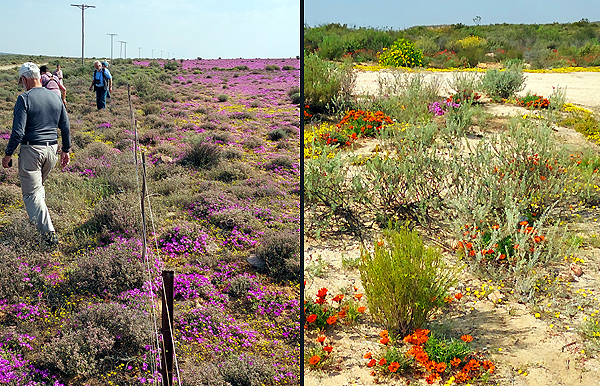

“Our interaction with Britain has been one of pain, death and dispossession, and of the dehumanisation of the African people. We do not mourn the death of Elizabeth.” The numbers are astounding. How many large wild flowers did we see in five days? How many billions? How many different colors? I can’t begin to answer that, but they covered every shade imaginable.

The numbers are astounding. How many large wild flowers did we see in five days? How many billions? How many different colors? I can’t begin to answer that, but they covered every shade imaginable. [For many more wild flower pictures of our trip in the Western Cape, go to Facebook AfricaAnswerMan.] Think about Africa. Then think about flowers. Must be spring and must be super-grand!

[For many more wild flower pictures of our trip in the Western Cape, go to Facebook AfricaAnswerMan.] Think about Africa. Then think about flowers. Must be spring and must be super-grand! South Africa is exquisitely beautiful and culturally devastatingly complex. It’s the bitter-sweet but intense experience I try to convey at the start of a South African trip.

South Africa is exquisitely beautiful and culturally devastatingly complex. It’s the bitter-sweet but intense experience I try to convey at the start of a South African trip. If you’ve never been to Stonehenge and Egypt, something’s missing in your understanding of either. Several thousand miles and two seas apart, both early societies moved 40-50 ton stones onto suspensions 4-5 meters high.

If you’ve never been to Stonehenge and Egypt, something’s missing in your understanding of either. Several thousand miles and two seas apart, both early societies moved 40-50 ton stones onto suspensions 4-5 meters high. I hear a giant ho-hum following the grunt-grunt of the lion walking through the night.

I hear a giant ho-hum following the grunt-grunt of the lion walking through the night. My followers might be more interested in the calamity that befell me than what I wanted to say but couldn’t because of the calamity. So as a result I’m going to very briefly tell you what I wasn’t able to say the last few days, first. Calamity last.

My followers might be more interested in the calamity that befell me than what I wanted to say but couldn’t because of the calamity. So as a result I’m going to very briefly tell you what I wasn’t able to say the last few days, first. Calamity last. Shortly before my first group was to kayak up to Hubbard Glacier in Alaska’s Russsel Fjord there was concern that the glacier was growing so fast that it would seal the fjord.

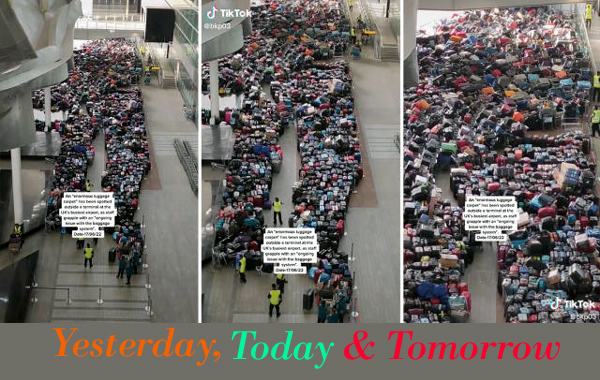

Shortly before my first group was to kayak up to Hubbard Glacier in Alaska’s Russsel Fjord there was concern that the glacier was growing so fast that it would seal the fjord. If you’re planning to take an airplane sometime in the next month or two… well, consider driving… or swimming … or just using your xBox. I didn’t mention trains, because in London anyway, they’re on strike.

If you’re planning to take an airplane sometime in the next month or two… well, consider driving… or swimming … or just using your xBox. I didn’t mention trains, because in London anyway, they’re on strike. I think the world’s economic and social systems are collapsing. That probably doesn’t surprise you as an off-the-cuff remark, sarcasm probably cast out not too seriously.

I think the world’s economic and social systems are collapsing. That probably doesn’t surprise you as an off-the-cuff remark, sarcasm probably cast out not too seriously. The “unlawful and

The “unlawful and