Are ecotourism and wildlife conservation in Africa so sacrosanct in the minds of their supporters that they’ve dodged proper regulation or perhaps even swerved off moral pathways?

Are ecotourism and wildlife conservation in Africa so sacrosanct in the minds of their supporters that they’ve dodged proper regulation or perhaps even swerved off moral pathways?

I obtained with pride a Conde Nast ecotourism award in 2004 for my client, Hoopoe Safaris of Tanzania. But in the decade since then my own ideas about ecotourism and NGO involvement in African conservation have changed.

There are two issues, here. The first is that “ecotourism” is no longer a legitimate marker for good tourism practices in Africa. The second is that wildlife NGOs have grown increasingly callous of the priorities of local populations. So the two are related. Both discount the preeminent interests of local people in the areas where they work.

The common thread that I’ve watch develop over the last decade is that western-driven “charity” or “aid” or “consultation” or “community based tourism” has grown increasingly detached from the people who theoretically will benefit from those efforts.

Even if there aren’t contextual conflicts, disputes about goals or methodology, the ignoring of the local populations’ interests spawns conflict. Imagine what you might feel if a Chinese NGO came into your suburban neighborhood and began research then implementation of plans to cultivate an herbal remedy … like garlic mustard… in the city parks. You would at least expect participation in the discussion, and you would become infuriated if you weren’t consulted.

In the last decade African populations have increased substantially, and their educational levels have grown exponentially. Most of Africa is well linked to the outside world through increased internet and cell phone access. This empowers the local communities to better scrutinize their so-called foreign benefactors.

ECOTOURISM IS A SHAM

The academic community has always been skeptical of ecotourism. A 2007 Harvard study of Tanzania ecotourism concluded that while most such projects seemed legitimate, there was a substantial percentage that weren’t. An analysis by Ohio State University in 2011 of Tanzania ecotourism was much more damning. The report actually named (accused) specific Tanzanian operators that were scamming tourists with the ploy of arguing their products were ecotouristic when they were anything but.

The above studies, and many more referenced within them, are convincing documents that ecotourism if not an outright scam is a very poorly formed idea. The initial theories might be good, but implementation seems impossible. And the Ohio State study in particular described why self-appointed certification authorities weren’t working, either, so that the notion of creating some universal standard is mute.

The UN initially thought otherwise. It promoted ecotourism but has since backed away from the idea. Almost a year ago exactly I posted several blogs citing the growing skepticism with ecotourism throughout the world. Nothing has changed; ecotourism as commonly applied in the marketing of travel is neither honest or good.

Khadija Sharife in the Africa Report summed it perfectly last week in the post’s title, “The Drunken Logic of Ecotourism.”

WILDLIFE NGO ARROGANCE

But in the year since I and many, many others pointed out the disservice that using the marketing ploy, “ecotourism,” does to local peoples, another foreign fixture of African life has emerged as equally unfair and misleading: wildlife NGOs.

It will be harder to convince you of this, I know. The loyalty that the world’s great animal savior organizations command is legend. It’s one thing to suggest that a tour company is scamming you while not serving the local populations well. It’s another to make this claim against the World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) or the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF).

WWF’s long involvement in Africa stands mostly as a fabulous contribution to baseline research and good management of threatened and endangered species. But as with the morphing of the idea of ecotourism into a marketing scam, it could be that WWF’s longevity of success gave it an unwarranted sense of propriety.

Its most serious conflict is in the Rufiji delta, the outskirts of the great Selous game reserve in Tanzania, which has come under increasing scrutiny because of its enormous hydroelectric potential. A much greater controversy actually than the WWF one I describe below is the World Bank’s program for a hydroelectric dam that could seriously disrupt The Selous and Rufiji delta basin.

But the World Bank’s mission to help developing countries grow can quite plausibly include draining a game reserve for additional electricity. Discussions are heated and ongoing, and everyone accepts one important debate is who should make the decision? Professionals weighing the overall value to Tanzanian society, or local people immediately impacted?

Quite unlike the World Bank, WWF skipped this important debate when it began programs to inhibit rice farming on the outskirts of The Selous. Local rice farmers were obviously the first to be impacted, but they were allowed no input into the decisions regarding the project.

The project mission was always suspect to me, but the rapid implementation without adequate consultation with the local population reeks of arrogance. The entire project has now collapsed into all sorts of criminal and unethical consequences. Eight WWF employees have resigned, plus the Tanzania country director, Stephen Mariki.

WWF should be complemented for trying to right the wrong, but the culture that led to their presumption of determining the life ways of local Tanzanian people is the real problem. And that will be a much harder thing to remedy than just abandoning one project. An overhaul in staff is a good start.

The current most egregious wildlife NGO controversy, however, is on no path to reconciliation because the organization, the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), continues to defend its position.

AWF encapsulates its overall mission in the phrase “heartlands.” Over the last several decades AWF created heartland areas throughout sub-Saharan Africa in which to concentrate its research and assistance. An essential purpose is to create wildlife corridors between established nationally gazetted protected wildlife areas like national parks to increase the potential for biodiversity.

Noble. The problem for some time has been to create these corridors, land must be acquired from private holders. This may have something to do with AWF’s decision to form a close partnership with the Nature Conservancy in 2007.

But what happens when farmers or other landholders don’t want to sell? AWF’s response has been high-handed and infuriated local communities.

In and around their large Manyara ranch holding in Tanzania, AWF negotiated versions of eminent domain with the Tanzanian government that caused enormous friction locally. And now in Kenya their acquisition of land (which they subsequently tried to deed over to a new Kenyan Laikipia National Park) is on track to totally cripple all their good efforts in East Africa.

AWF insists it has been playing by the rules. But two thousand Samburu people don’t care if they were playing by the rules or not; they insist with credibility that they have been displaced against their will.

Unlike WWF, AWF seems to be digging in its heels for a fight that will emasculate it. And if it goes down as I expect it will, so will the reputation and memories of good work that wildlife NGOs have been undertaking for decades in Africa.

Why is AWF resisting an acceptable settlement? AWF is a much younger organization than WWF, and its donor base is much smaller than WWF, much less publicly than individually endowed.

Nature Conservancy is itself a less publicly endowed organization limited to wealthy landowners mostly in Illinois. It could be that these two closely held NGOs feel less vulnerable to public opinion than a more globally funded organization like WWF.

Both these situations — ecotourism as a sham and wildlife NGOs indifferent to local community needs — represent not just outside interference but patent indifference to the preeminent rights of local people. And because that indifference has been so arrogant – dare one say “racist”? – it led these otherwise exemplary organizations into believing they could discount local community interests.

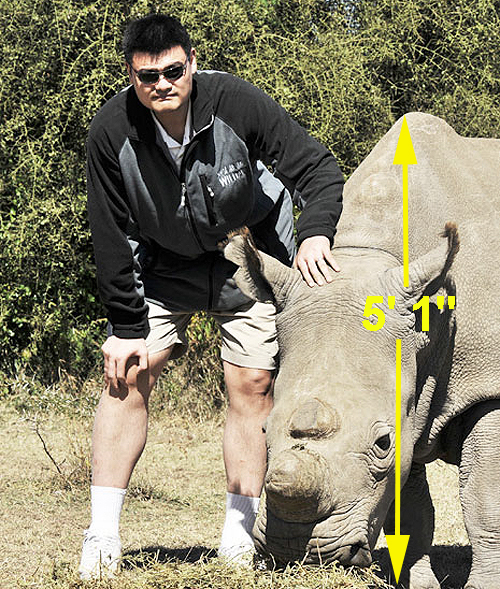

Africa is developing so rapidly I can see incidents of polite refusal, so to speak, of tourist projects and foreign wildlife programs that are put to bed rather easily. The recent controversy in the Kenyan Wildlife Service (KWS) involving the translocation of rhino is a good example of “local populations” politely indicting foreign organizations trying to tell them what to do.

But in heated political arenas, this politeness will be lost. WWF had to back down altogether, fire staff and refund grants. AWF should do the same. When sensibilities are exchanged for political control, foreign tour companies and foreign wildlife NGOs have no hope of prevailing.

Beware, guys. A lot of good has come from your work in the last half century. Don’t blow it.

Two new monkeys discovered in Africa since 2003 suggest the continent is becoming more peaceful and interaction with scientists from the west has become healthier.

Two new monkeys discovered in Africa since 2003 suggest the continent is becoming more peaceful and interaction with scientists from the west has become healthier.