Children really do better than their parents on a family safari in all cases, no matter how difficult or how easy it might be. And that makes sense.

Children really do better than their parents on a family safari in all cases, no matter how difficult or how easy it might be. And that makes sense.

The first question I get from a parent or grandparent considering taking their family on safari is what is the ideal age, or actually more often, what is too young to go?

The Felsenthal Family Safari organized by Babu Eddie just ended, and as I reflect on that ten days a lot of the answers I’ve given over the years are confirmed.

Children of virtually any age are as different as any person of any age, so the qualification that my generalization might not apply to your particular child is a very important one. I’ve had three-year-olds that two decades later would recite the days on safari with rapture. And I’ve had many repeat adult clients that for the life of them couldn’t remember what they’d done before.

But generalize I will. The best ages for children on safari are between 8 and 16. The Felsenthals had a 5-year-old and two 7-year-olds and the safari worked well. And last year I guided a family with university students, and they were outstanding safari travelers.

But in general kids under 8 lack the stamina a safari requires, and kids over 16 lack any interest for much except being home with their friends.

How this generalization was torn to smithereens by the Felsenthals! To begin with, I was amazed at how much they wanted to do as a family. With near unanimity the family pressed the envelope of reasonable game driving. According to my notes, we had four game drives of 12 hours!

And quite a few of ten!

Part of this was because a family safari usually does better with all-day drives with a picnic lunch, than with the traditional early morning and late afternoon drives separated by a long mid-day period in camp with lunch.

It’s easier for a family to get going in full light and without an early wakeup. But in my memory I don’t remember such enthusiasm as the Felsenthals.

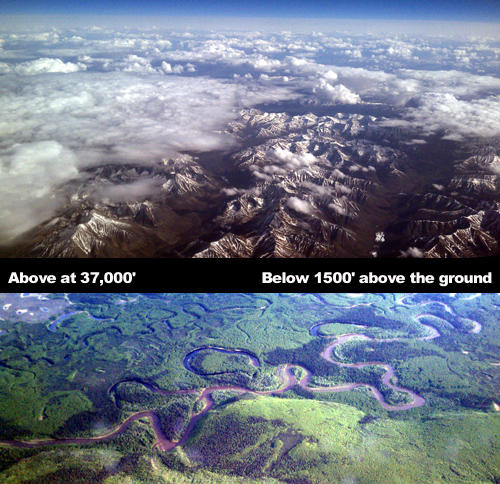

We were unable to get satisfactory accommodation near the expected whereabouts of the migration in northern Tanzania, and that became the motivation for the 12-hour day. We left the central Serengeti around 7 a.m. and traveled to the Kenyan border, returning around 7 p.m.

And … we found the migration! Big time, in fact. It was a relief to me, of course, and the family was fully aware that the information we had garnered might not have been accurate. But as it turned out, it was.

And on the way back, 7-year-old Nate simply fell asleep on the back seat of the cruiser, certainly the most bumpy part of the car!

I was amazed day after day how these young kids all chose to go out for hours longer than the average adult safari. But then I’d learned long ago that the stress of such a long day really hangs on the parents, not the kids.

They are understandably worried that such a trial of bumpy roads and long periods of seeing nothing foments the boredom that often turns into anxiety or peevishness in kids. But it doesn’t. And my saying so from experience after experience doesn’t seem to convince anyone.

But it doesn’t. Kids always … and I mean always … end up doing better than their parents on safari, and particularly when the safari is challenged by long drives and bumpy roads.

That isn’t to say they’re constantly enthused and wrapped in attention. It just means that the parents do more poorly than they do.

So the maxim stands: analyze your own stamina and interest, parents and grandparents, as the threshold of what the family safari should do. The kids will always work into it just fine!

I can’t thank the Felsenthals enough for giving me such a fine experience, too! Our elephant encounters in Tarangire were exceptional and so exciting. There was even a trunk into the pop-top roof!

In one morning around Seronera, we saw four leopard and twelve lion. Not to mention several hundred zebra, and a giant croc guarding its zebra kill.

We found the migration, a beautiful and always awe inspiring site. And as usual with migration experiences, there was something extremely unusual and dramatic: we saw at least four hundred vultures collected together near a bit of water drying their wings.

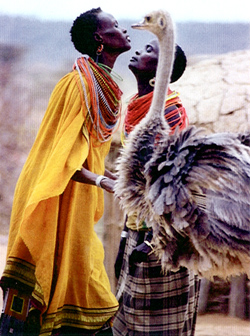

The Felsenthal kids spent a good hour or two mingling with school kids from Arusha on a field trip safari, and taught them tic-tac-toe! The Felsenthal boys played frisby on the endless plains of Lemuta, not another car in sight for 50 miles, even as a single Maasai teenager walked across this enormous veld to greet us.

We saw hyaena relocating babies that couldn’t have been more than a day old. We watched a family of lion unsuccessfully hunt warthog that successfully held up backwards into a hole!

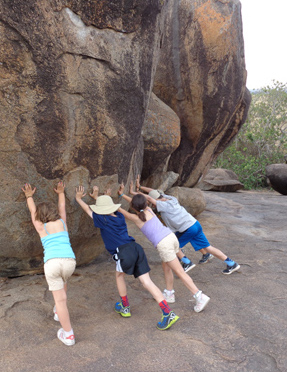

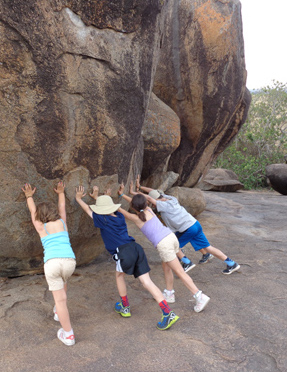

We walked around the actual place where Zinj, the Nutcracker Man, was found, and walked over the Shifting Sands hills that themselves walk over the veld. The kids pounded the magical Ngong Rock with granite stones to recreate the dream booms that called Maasai to their last conclave in 1972.

And for icing on the cake, hardly a half hour before we took off on the charter that started the journey home, a lionness flopped in the shade of the kids’ safari car!

There’s just nothing as good as a family safari. And no one as happy as the kids!

On Safari! Today I begin seven weeks in Africa! You can follow my exploits, adventures and guiding into sub-Saharan Africa in this space!

On Safari! Today I begin seven weeks in Africa! You can follow my exploits, adventures and guiding into sub-Saharan Africa in this space!