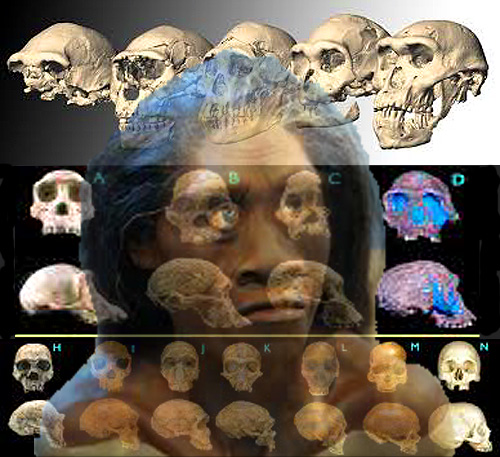

Paleontology — especially in Africa — is just simply growing in leaps and bounds. Not too many years ago when it was presumed we (homo sapiens sapiens) evolved in a linear way from just a few creatures that preceded us and followed the apes, enormous attention was applied to finding the gaps, or “missing links” in that line.

That’s all blown away, now. The last few decades have proved so rich with discoveries showing that there were many, perhaps many many species of “early man.” Even the Neanderthals, who were likely not on our own linear evolutionary line, probably had cousins who died out.

So as the universe of potential discovery grows, so does the depth, range and interest of scientists, and that as you can imagine leads to more and more discoveries.

Here are the high points of 2015:

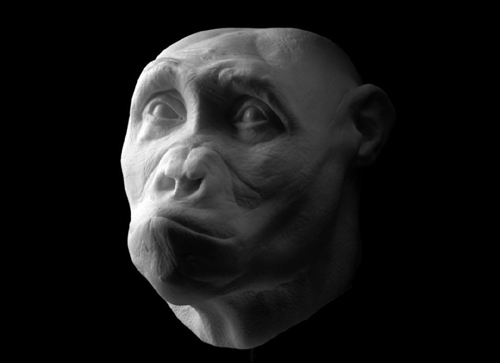

Most important certainly was the announcement of the initial conclusions about Homo Naledi, a new early man species found in South Africa in 2013.

I don’t agree with all the conclusions, particularly that the cave in which the 15 individuals were found was a burial site, but there are many other equally interesting conclusions that come from this remarkable discovery.

First and foremost, the appendages (hands and feet) of the creature were very close to our own, even though the brain size suggested a very primitive and early creature that would, for example, predate both homo erectus and homo habilis.

The individuals were astoundingly complete, at least in terms of what most 2½ million year old fossils normally look like.

And from my layman point of view, the incredible transparency of the discovery, from almost the moment it was found to the invitation to scientists worldwide to analysis the data, marked a real turning point in the until to now bitter infighting common among paleontologists.

Some other important bones discovered included fingers! Million-year old fingers aren’t easy to come by, and the discovery in Olduvai parallels Naledi’s suggestion that our physical traits existed much earlier in the hominin record than previously thought.

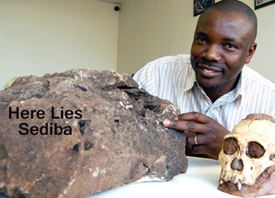

In the category of “keeps getting older” scientists also in South Africa found a homo habilis dated to almost 3 million years old. This predates by nearly a half million years the next oldest habilis find and resurrects suggestions this is our own most immediate ancestor.

This was hotly contested, by the way, with another 2015 discovery in Georgia of another homo erectus. The scientists on this site insist this creature is in line for our most immediate ancestor.

Moving away from old bones, there were scores of new tool finds, deeper analysis of existing data and actual field science regarding the dynamics of evolution itself.

Stone tools were very many years presumed to mean the user was an early man. That’s changed as we documented less than mankind, like chimpkind, also uses them.

In 2015 scientists announced finding what they claimed were the oldest fossil stone tools on record, more than 3 million years old. I disagree with their conclusion that this find by itself pushes back “humanness,” but it remains an argument that still carries weight.

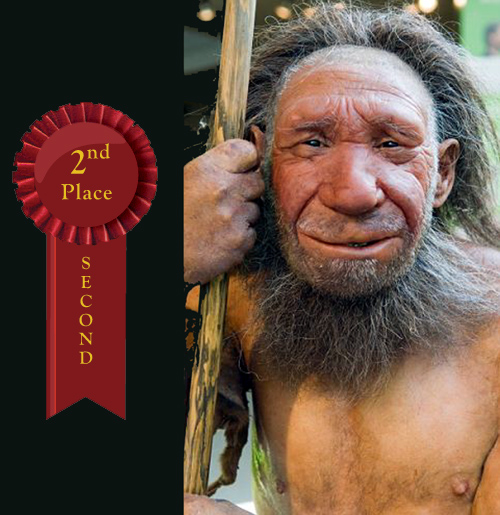

One of the hottest topics this decade is trying to figure out why we prevailed and Neanderthals didn’t. Some really clever research suggests at least one of the reasons is that we had … and enjoyed music! (And that the big guy didn’t.)

Some may fear I’m sinking into the arcane, but there was also some really fascinating research on Africa’s cichlid fishes that qualifies the value of natural selection! Cool stuff.

Some people lay on their back and peer into the heavens, wondering what’s out there. I do sometimes as well, but I much prefer peering into the distant past and wondering what marvels of the universe transformed us into what we are, today!

(For my summary of all the top 10 stories in Africa in 2015, click here.)