Free higher education is becoming an explosive issue in Africa.

Free higher education is becoming an explosive issue in Africa.

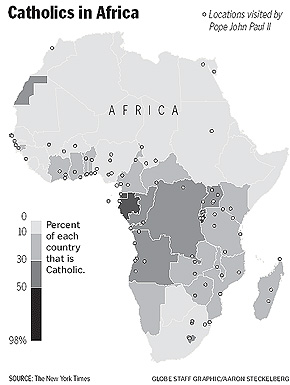

Until the turn of the millennium most higher education throughout Africa was completely free, as in much of Europe it still is. The model, in fact, for most African countries was Germany.

But today about a quarter of an African university student’s costs are borne by the student. In South Africa it just became more than a third.

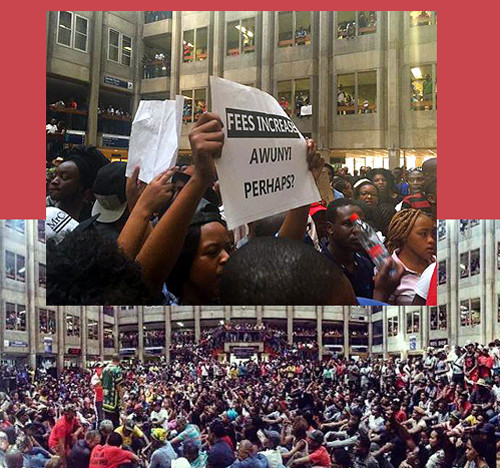

South Africa’s most prominent university remains closed today after protests against fees that began Wednesday.

The University’s CEO, its Vice-Chancellor, raced back to Johannesburg to address today’s massive student demonstration morning and was followed on national TV by the country’s Minister of Education, but the students have not been placated and the protest continues.

You can follow this massive and explosive event on twitter at #WitsFeesMustFall.

The 10.5% increase in fees announced last week will push a university student’s contribution to just over half of all estimated costs.

The arguments on both sides are identical to arguments in the United States, Kenya or virtually anywhere in the world where higher education is not free:

“The government needs to invest significantly more … for public universities. This is the kind of expenditure that will pay for itself… Money given to universities is money that alleviates poverty, creates employment and drives cutting-edge research and innovation,” writes student leader, Saul Musker, in today’s Daily Maverick.

“Indeed, the actual social, political and economic costs of under-investing in higher education are far greater than the additional expenditure…. If the ultimate goal of the government is to create an equal and prosperous society… this is an obvious choice.”

Contractual costs particularly salaries are increasing much faster than government subsidies for them; utilities and other operating costs are unexpectedly high, and unique to South Africa, the Rand has fallen by 22% against the dollar and much of the university’s costs are dollar based.

In fact, government subsidies have actually fallen, as they have throughout much of America.

So as in America we have an extraordinary situation where both the protesters and their targets are in agreement. The problem, of course, is the government that funds them both.

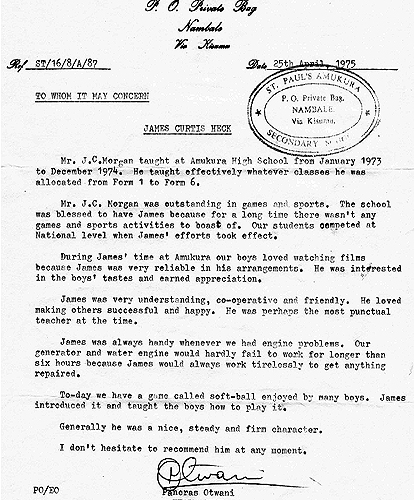

Governments ordinarily reduce their subsidies with additional loan mechanisms and “bursaries” or scholarships. But in many places like Kenya that’s proved self-defeating, because the loans can’t be recovered and the process of awarding scholarships is cumbersome and often corrupt.

The result is a spiraling downwards of government support, as forward budgets are often based on presumptions of recovering loans while funds for bursaries are often underused for getting tangled in confusing regulations.

Opposition politicians often clamor onto the bandwagon that there should be more government support, but once in power, they become hamstrung by budget necessities.

Governments are rarely so forward-thinking as to invest in a student whose productivity is many political cycles in the future. Mature, successful governments like Germany and the Scandinavian countries should be a model for us all, but in the U.S. archaic conservative forces hold us back, and in Africa, the critical capital mass capable of this policy just hasn’t yet been achieved.

So the gap between the haves and have-nots widens even further.

Only this time it’s not just a gap of wealth, it’s a gap of intelligence.