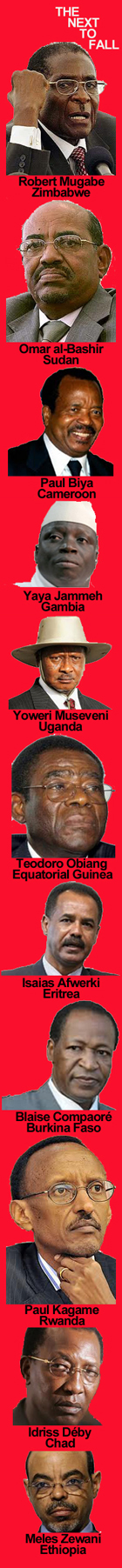

Three African despots down. Eleven to go. Here’s my list and predictions of when the last of the African dictators will fall.

Three African despots down. Eleven to go. Here’s my list and predictions of when the last of the African dictators will fall.

Is it possible to think of a world without dictators? Can you imagine no Kim Jong Il, the “Stans” with free wifi elections, Hugo sent back to his banana farm or Ahmadinejad retired as a Fox News anchor?

Is it possible to think of a world without dictators? Can you imagine no Kim Jong Il, the “Stans” with free wifi elections, Hugo sent back to his banana farm or Ahmadinejad retired as a Fox News anchor?

I can’t speak about the rest of the world, but yes, I can imagine an Africa without ruthless despots, and Twevolution is knocking them down the continent from top to bottom. Only a few years ago I would have thought this impossible.

What’s happened in Africa started with this near obsessive demand for education, and over the years I was so critical of all sorts of different African forms of education for all sorts of different reasons. But that all seems so trivial, now. Whatever flawed system might have delivered it, delivered it it did. From Tanzania’s mandated free education in the early years of independence, to more sophisticated forms in Egypt, it worked.

I think I was too focused on what was being taught, the curriculum, rather than just the teaching itself. Teaching young kids – even when forced down their throats or teaching “incorrect” things – obviously instills curiosity.

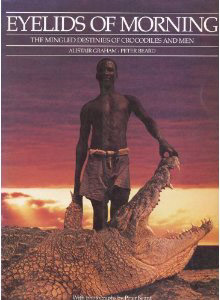

In my life time, Africa has made the longest journey in education of any part of the world. When I began my career there in the early 1970s, there were vast portions of the continent that didn’t even know there was more to the universe than themselves.

My wife and I brought the first refrigerator into a remote part of western Kenya. Powered by natural gas, it nearly installed me as a local despot myself, or a shaman. When ice cubes were placed on the hands of children, they thought I was burning them to death.

How remarkably different that place in western Kenya is, today, with nascent global call centers and plans for a solar panel industry. What must grandma think?

The second critical component to today’s dramatic political change is the internet.

That’s twevolution. A young Kenyan woman started the whole social networking organization of civil disobedience when Kenya imploded after its last election. Ory Okolloh spearheaded the founding of Ushahidi and is now Google’s Policy Manager for Africa.

But while the internet may be the new “weapon” of revolutionary change, it had a much much greater impact much earlier. I remember before cheap cell phones and easy access to computers in Kenya the dozens and dozens of internet cafes in Nairobi.

And the kids were packed into them like sardines! What were they doing? Playing games? Looking for a job? Or, maybe, learning about the better things in the life… Or, maybe, about the gross injustices that divide the world’s privileged from those who serve the privileged?

There are still pretty bad guys in control of 11 of Africa’s 54 countries. I can imagine every one of them gone in the next decade.

They fall broadly into two categories: 7 zealots and 4 victims. The victims will fall last and perhaps not with more than a thud. But the zealots will tumble into al-Jazeera videos screaming.

The zealots are composed of widely different men whose path to tyranny was varied. But they now share a narcissistic certainty, a near divine belief, that they should rule no matter what. Their countries of Zimbabwe, Sudan, Gambia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Uganda are in various stages of abject servitude.

They are making themselves, their friends and families wealthy often with impunity at the expense of their citizens. They believe so much in their self-conceived right to rule that they often fail to hide their crimes, deluded that they can do no wrong, or perhaps that there are none remotely capable of challenging them.

How wrong Gadhafi was.

These guys go first.

The second batch I even find sympathy for, but they’re on the way out nonetheless. I call them victims because essentially they started as true liberators with extremely lofty ideals and plans, but they got ensnared in societies with the deepest ethnic divisions in the continent, and with a concomitant division of education.

Rwanda, Chad, Eritrea and Ethiopia are today headed by ruthless men who are nonetheless loved by a large segment of their population, the segment from which they were born.

They believe, quite possibly truthfully, that loosening the reigns of dictatorship will bring catastrophe on their entire country as it reverts to the chaos from which they long ago thought they liberated it. These victims at least ostensibly put “country” before “self.” The zealots don’t even have this as a pretense.

That’s Africa. Where education delivered the dreams and the internet facilitated revolutionary change. Will the rest of the world follow suit?