A paid staffer for Michelle Bachmann was imprisoned in Uganda for terrorism and illicit arms deals with Congo rebels linked to the current serious turmoil in Uganda. Did you know about this?!

A paid staffer for Michelle Bachmann was imprisoned in Uganda for terrorism and illicit arms deals with Congo rebels linked to the current serious turmoil in Uganda. Did you know about this?!

Last week Peter Waldron convened evangelical Iowa ministers in Des Moines to discuss political strategy to help Bachmann.

Five years ago, according to The Atlantic which broke the story on August 17, he was sent to Uganda’s Luriza Prison convicted of terrorism and illicit arms dealing. My Google pretags and all the media I read about Africa didn’t bring it to my attention.

I do read The Atlantic from time to time, but it took a casual look at a Ugandan’s blog, yesterday, for me to finally learn about it. Obviously I have serious interest in this, but shouldn’t the whole world have serious interest in this!?

There’s a lot more to this story. Fast forward to today: Waldron has tried to turn this normally terminating revelation to his profit. He’s making a movie about himself, and will portray his time in Ugandan prisons as a hero’s suffering for righteous causes.

Holy Smothering Smokes! This is absolutely incredible! I know it’s what the right does all the time, twists bad into good. But this is unbelievable:

Bachmann’s press secretary, Alice Stewart, replied in an email to The Atlantic: ‘We are fortunate to have him [Waldron] on our team and look forward to having him expanding his efforts in several states.’

He’s a mercenary! He’s an arms dealer! He’s a crook and about as bad a guy as you can get!

More. Here’s what the respected Ugandan blogger, Mark Jordahl, said about Waldron two days after the story appeared:

“I happen to know some people who … went to his apartment one evening. The table was covered with pornography, and there were a number of attractive young ladies hanging around. I’m sure he was just talking to them about the evils of pornography.”

And, oh by the way, he’s the Michele Bachmann campaign’s faith advisor. Paid. Still. Today.

Oh-oh, and by the way, after The Atlantic published the story, the website for his movie was shut down. Fortunately, The Atlantic had transcribed the trailer that was on YouTube (which was also taken down):

“Lebanon. Iraq. Syria. Afghanistan. Pakistan. Uganda. India. For over thirty years, his family never knew where he went — never knew what he did. Based on a true story, Dr. Peter Waldron was on a mission. Was he a businessman, a preacher, a spy? Tortured and facing a firing squad, he never broke his oath of silence. What secret was worth the ultimate price?”

A month after being imprisoned for up to life, Waldron was deported from Uganda. According to Waldron, he was freed “thanks to the Bush Administration.”

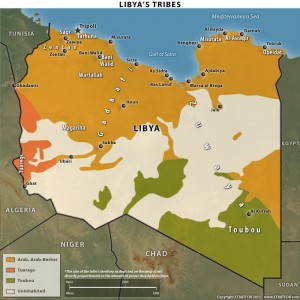

Now there’s an awful lot to this story we don’t know, and I think it would make a fascinating investigation for some serious journalist. Who were those others arrested, charged and imprisoned with him? All we know so far is that they were Africans involved in the civil war in The Congo. When Waldron was deported, so were they.

Why was he in Uganda in the first place?

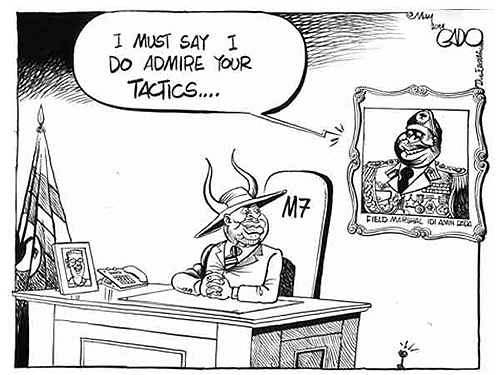

One of Waldron’s friends, Dave Racer, told the Uganda Monitor that Waldron “was a friend” of Uganda President Yoweri Museveni.

A friend of the rising dictator, Yoweri Museveni, is just the kind of person who would be whisked out of the country before the opposition got their hands on him and revelations would pour to earth.

But what revelations?

The Atlantic reported local allegations that he was working with Congolese rebel militia members to capture a warlord, Joseph Kony, in order to claim a $1.7 million bounty offered by the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Here’s my fundamental lesson from all of this. There is a fact or two no one can dispute. Peter Waldron was imprisoned in Uganda for alleged terrorism. Police confiscated lots of money and serious weapons from his home. He was arrested with a group of known foreign (Congolese) rebels. Then, suddenly and in violation of Ugandan law, he was deported.

He tried to champion this and other episodes of his life in a movie the forward publicity of which was then removed from public view when this story broke.

He works for the Michele Bachmann campaign as a faith advisor.

The rest is here say, although I put a lot of personal credibility in my friend and blogger, Mark Jordahl, who reports through another level of here say that Waldron didn’t appear to evening visitors at his home to be that upstanding a guy.

Forget about the here say. Let him tie up all the loose ends of his mysterious tale, or let the woman who professes such high and mighty morality dump him from her campaign.

And presuming neither will happen, the lesson ultimately we learn is that at least in Republican politics nothing matters anymore but pure fantasy.

Good. Lesson learned. But why did this take such effort? Why did The Atlantic story not gain traction in the greater media? Why is Waldron still a Bachmann staffer?

Because Uganda doesn’t mean diddly squat to Americans? Because arms dealing and bounty hunting is good experience for “faith advisers”?

Whoa, that mojo got spirit!