The pressure of rapidly growing human populations has stimulated exciting new research on how to keep Africa wild.

The pressure of rapidly growing human populations has stimulated exciting new research on how to keep Africa wild.

All over the world developed communities flirt with the wild areas they erase. Of the 25 “greenist cities” in the world, Vienna is at the top followed closely by Singapore and Sydney. Hong Kong is 4th. Rio is 5th and London is 6th.

London is actually the largest city in area of that list above, so its nearly 40% green space is impressive. (There are five American cities on the list of 24: New York, San Francisco, Portland, Los Angeles and Chicago.)

But all that “green space” isn’t exactly what Africans are trying to save. London’s exquisite gardens are mostly maintained by progressive income taxes and as with the taxed’s ancestral gameskeepers, thousands of green space workers hired by the city clip, fertilize and weed with the precision of a diamond cutter.

‘If a fox don’t belong in Burnham Common, best get the damn thing out a’ there.’

It’s much different in Africa.

Nairobi National Park, which is a growing favorite of the sentimental generation of which I consider myself a part, has no grass mowers. Very little intervention management occurs.

Rather, most efforts are concentrated in simply keeping the wild area from shrinking. Since much of developed Africa like Texas is grassland or scrubland, dainty-ing-up the hedge row isn’t one of the chores.

No, the principal focus in Africa is not with the green space, but the wild space.

East Africa sits about in the middle of the Great Rift Valley, and this is earth’s cornucopia. A fifth to a quarter of all animals (excludes birds and fish) are found in the Great Rift.

More and more protecting this biodiversity means expertly treating orphaned animals and refining ways to reintroduce them into the wild. Dame Daphne Sheldrick’s famous elephant orphanage at Nairobi National Park is the most well known, but by no means the largest or most important.

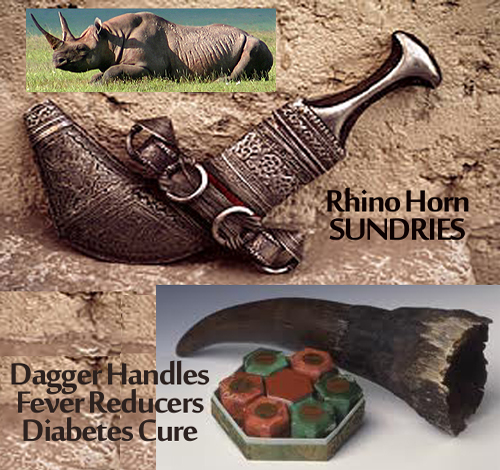

Almost all the largest animals found today in Kenya’s Nakuru National Park have been reintroduced or are descendants from reintroduced animals.

That’s quite impressive and includes dozens of rhinos, giraffe, buffalo and more. They live a totally unmanaged, wild existence, despite the massive fence that confines them to the 73 sq. miles, larger than the city of St. Louis.

These animals are as essential to the African ecosystem as the bromelias are to Hyde Park. So Africans have a bit more of a challenge than London gardeners.

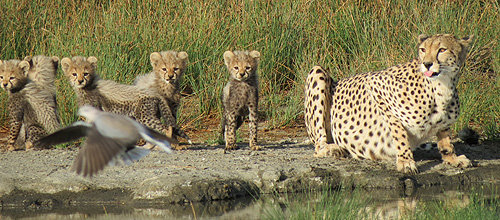

Genius comes from challenge, and as counterintuitive as it seems, researchers at a monkey sanctuary in Kenya have discovered ways to “train an animal to be wild.”

“Clicker Training” is right out of Pavlov, behavior modification. An orphaned monkey at the Colobus Conservation Centre in Kenya is “taught” to be “untaught.”

After being nurtured to health, the monkey learns to do what its trainer wants for the reward of a peanut. The animal subsequently learns that the peanut reward occurs when there is a “click” from a relatively unoffensive clicking device.

Once ingrained the peanut reward can actually be removed, and the monkey continues to behave as managed by the click alone.

Slowly, the trainer clicks the monkey higher and higher into the canopy of the forest, where it begins to find its own food. The clicks can even be directed to move the monkey away from curious visitors.

Ultimately, the clicks can train the monkey to ignore the clicks.

From unwild to wild.

Lammergeirers over the Narok plains, elephants into Tsavo, hyrax into the frontier, chimps back to the Kafue … dozens and dozens of organizations in Africa today are doing everything they can to protect the continent’s treasured biodiversity.

And if the great metropolis of Nairobi can tower over Nairobi National Park without destroying it, Africa will become as modern as New York but remain as wild as the Congo.