For sure a melancholic tale: Lions survive by growing tame enough to live side-by-side with people.

For sure a melancholic tale: Lions survive by growing tame enough to live side-by-side with people.

Last night’s PBS premiere of ‘Wandering Lions’ is one of the best nature documentaries I’ve seen recently. It tells a hopeful story of India’s critically endangered lions.

The lion population in India for my entire life time has been contained to a small 100 sq. mile sanctuary in southern Gujarat state called Gir. Also over my life time a huge periphery, another 400 sq. miles, was created where people and wildlife coexist. So today you’ll read of the 500 sq. mile park, somewhat misleading.

But it worked is the point. In 1968 the number of remaining lions in India was 168. Gir lions today number around 540, a remarkable success story that seems on track to continue.

Gir lion have been snatched from the brink of extinction into a genetically diverse enough population to be self-sustaining.

The Nature film documents a few days in the life of these lions, which also documents the life of Indian farmers who coexist with them.

I’m a bit skeptical about the partnership between man and beast that the film tries to convey: that Indian farmers have come to rely on the beasts to kill the antelope that would otherwise maul their cows or eat their grain crops.

It’s not possible for even the most demanding lion to harvest enough of Gir’s wildlife to make any kind of significant dent in the boar’s or antelopes’ effects on farming. I think that the real story is that the farmers won’t kill animals, whether antelope or lion.

A more important scene in the film documents a night of three Indian farmers who walk into their fields with sticks ostensibly to chase the antelope away. Instead they watch lion do it.

I don’t think that establishes the relationship the film suggests.

What is more telling is another part of the film that describes a lioness who killed a person, was captured but then released and not herself killed as would be the case almost anywhere else in the world.

The reason given was that the investigation determined that she was not, in fact, a “man-eater” but simply a mother protecting cubs.

I suspect that was determined during the deposition part of the investigation?

Regardless the outcome is absolutely positive for lion. And apparently over my life time nowhere near the animosity towards lion developed in Gujarat as in sub-Saharan Africa.

Why? Not because of tourism. As the film points out there’s no tourism in Gir: no lodges, no tour companies, no vehicles, and the difficulty in getting to the area is manifest.

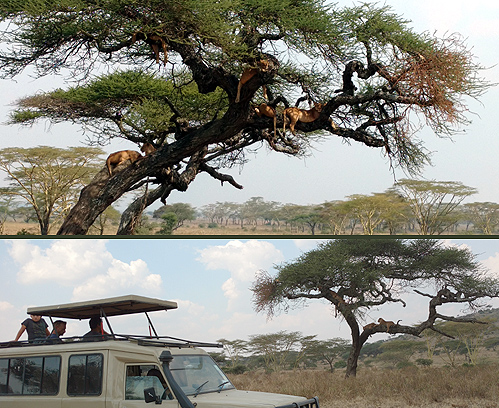

That isn’t to say the people living there wouldn’t love to have tourism. It’s just that the place is too remote and the animals … well, in a sense, too tame. The film has numerous scenes of cars, motorbikes and even villagers on foot right next to lions.

Prior to 1968 there may have been animosity towards lions, because the numbers of lion were tanking then. Shortly thereafter the Indian government began partnering with a number of wildlife organizations to save the wildlife. The numbers attest to this success.

But let’s go further, be clear: Government programs in India are notoriously unsuccessful. What’s different about this one?

The film and virtually all the materials that promote Gir National Park always reference the fact that Gujaratis are vegetarians. It’s actually a bit more serious than that: they’re vegetarians because their culture forbids killing life even for food.

That’s the key to this successful interdependence: a culture that has existed forever, a first principal of Gujarat peoples: let the animals live.

* * *

When I first started in this business the Gir lion was presumed a separate sub-species.

But “Asiatic lions” don’t actually exist, according to the world’s authority on taxonomy, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

DNA research proves they are not a sub-species. There is a yet to be confirmed suggestion in that research that the Gir lions when viewed with the handful of northern African lions that still exist might then constitute a subspecies, but that remains unsettled.

Fanciful photos of thirty years ago tried to portray Gir lions as physically different, with strange manes that didn’t begin until their neck, but those photos have now been debunked as anomalies. Genetically for the time being all lions on earth are close enough to be lumped into the same species.

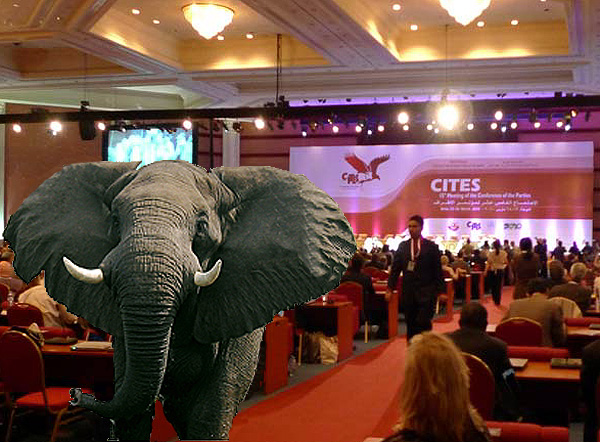

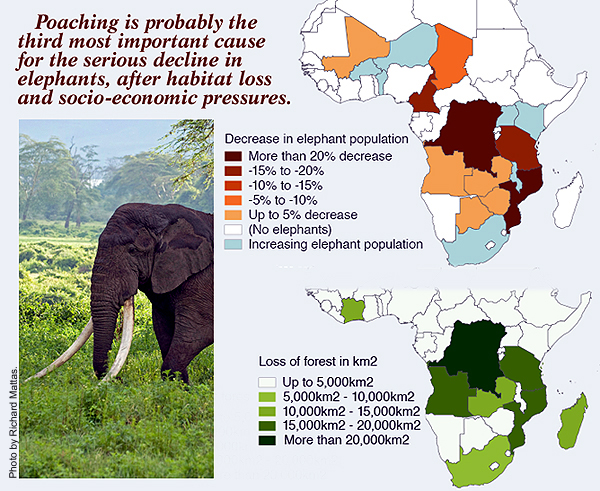

World authorities were unable last week to adequately address the “elephant problem” at COP17 even as more and more elephant attacks are reported.

World authorities were unable last week to adequately address the “elephant problem” at COP17 even as more and more elephant attacks are reported. COP17, the CITES treaty working group, is winding down like a firecracker with the biggest boom possibly yet to come. Southern African countries prevailed in a bitter fight to keep all elephants from being listed as imminently going extinct, and the fight over lions begins today.

COP17, the CITES treaty working group, is winding down like a firecracker with the biggest boom possibly yet to come. Southern African countries prevailed in a bitter fight to keep all elephants from being listed as imminently going extinct, and the fight over lions begins today. More than two thousand ardent scientists and advocates are in Johannesburg today preparing for next year’s CITES. Historical treaties like the Geneva Convention may actually effect our daily lives more noticeably but only CITES has attracted such global consensus that enforcement is aggressive and routine.

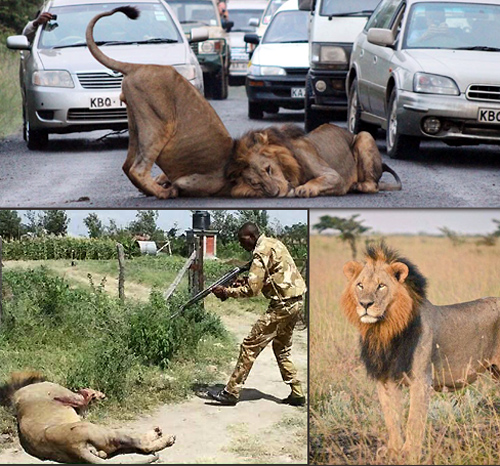

More than two thousand ardent scientists and advocates are in Johannesburg today preparing for next year’s CITES. Historical treaties like the Geneva Convention may actually effect our daily lives more noticeably but only CITES has attracted such global consensus that enforcement is aggressive and routine. The great King of Beasts might soon be something less. It’s not just the statistical decline. It’s losing its glamor. It’s important that we outsiders don’t force this issue. Africans are handling it just fine.

The great King of Beasts might soon be something less. It’s not just the statistical decline. It’s losing its glamor. It’s important that we outsiders don’t force this issue. Africans are handling it just fine. There is not just one giraffe animal. There are

There is not just one giraffe animal. There are  Last Wednesday the

Last Wednesday the