Day 1 of 4 in the Serengeti: a lion kill, a cheetah kill, and most exciting of all, a reasonable hunk of the great migration!

Day 1 of 4 in the Serengeti: a lion kill, a cheetah kill, and most exciting of all, a reasonable hunk of the great migration!

The reason we found the migration was because the people I’m with are so incredibly enthusiastic. It’s that simple!

I expect that most of the migration is in the center of the park where we go, tomorrow. We’re currently in the far southwest. The information we garnered from the many other drivers here at Ndutu Lodge, as well as from rangers and what we could pick out of the radio traffic, suggested no large herds in this area.

So we headed out at dawn ready for anything … but the great herds.

We saw five cheetah and ten lion including a lion kill and a cheetah kill plus an unsuccessful cheetah hunting a baby wildebeest. That event failed when the mother wildebeest intervened at the last possible moment.

We had a fabulous breakfast on the plains packaged for us in Ndutu’s famous picnic baskets and we’d been out for five hours. We were an hour from camp so I was ready to call it a morning and return for lunch, but…

…Justin, one of my outstanding long-serving driver/guides, heard over the radio that 3 days previously wild dog had been seen another 90 minutes out from the lodge. Was anyone interested? That was in a pretty remote place.

The chances seemed extremely thin. It could mean at least an 8-hour game drive and no lunch!

Soon the entire group, all three vehicles was on board with the idea, and off we went – in the opposite direction of lunch!

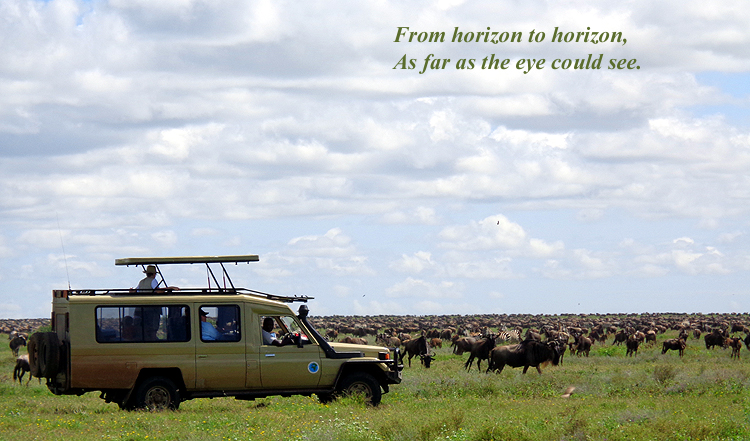

Hardly a half hour later I began to see a very large number of wildebeest.

Most of the wildebeest we had seen until now were in wildly dispersed migratory files heading to the center of the park, where we expect to be tomorrow.

Twice, lost baby wildebeest had attached themselves to us, once on the Lemuta plains and once this morning at breakfast.

On the plains the poor 2-week old ran itself close to death trying to keep up with our speedy Landcruiser. We finally led it to a water hole with hyaena looking on.

This morning we were packing up breakfast when another two-week old showed up blarting. It pranced back and forth hardly 20 feet away from us. There were no other animals near us, much less its mother.

There are all sorts of reasons baby wildebeest get separated from their mothers, but one important one is that the migratory files are moving so quickly; and they were all moving in the same direction. I was pretty convinced that the big herds were all in the center off the park.

But before long on our extended trek to find wild dog we were among very large herds, not just of wildebeest, but zebra, gazelle and all sorts of other animals. We probably passed 500 eland.

Everything was located in and around the Kerio Valley, west southwest of Ngorongoro not really too far from the village of Endulen. Nobody suggested this area to us. None of the radio traffic or driver/guides or rangers even thought that part of the migration would be here.

The main reason no one knew about this is precisely because no one travels to this place! It’s deemed far too far from established tracks or lodges. The only reason we found it, is because my group is so tirelessly enthusiastic!

Five people have been with me for 30 days, yet they were among those lobbying for staying out!

So no, we didn’t see the wild dog. My predictions on that count were right: the chances of finding some family of animals in a place they were three days previously is ridiculously slim.

But it was just the excuse these wonderful adventurers needed to stay out, go further, do more. And what a reward we got!

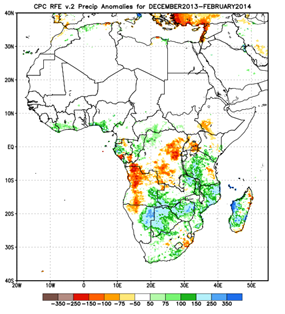

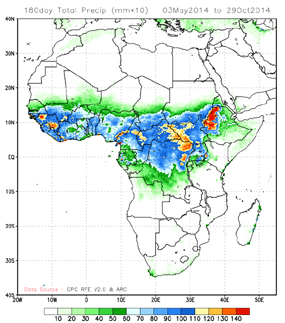

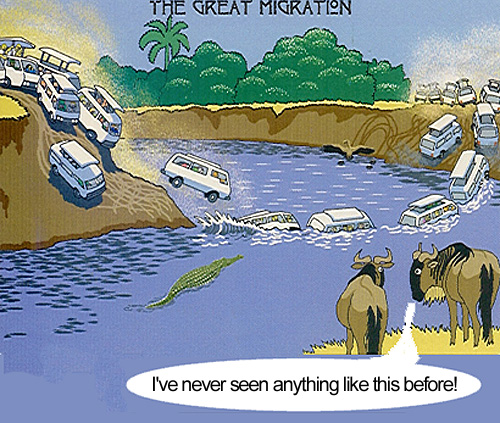

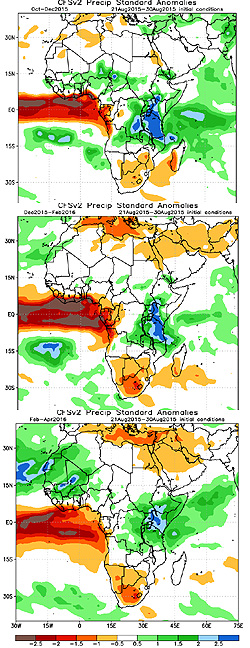

The greatest wildlife spectacle on earth has become unpredictable because of climate change, as awesome as it remains.

The greatest wildlife spectacle on earth has become unpredictable because of climate change, as awesome as it remains.