Jim is out of cell phone or internet ranges. Come back next Monday when his actual adventures will replace this post holder.

Jim is out of cell phone or internet ranges. Come back next Monday when his actual adventures will replace this post holder.

Last May I blogged about this sad story in partial error, resulting in my concession that the blog had enough misleading information to be adjusted. The incomplete discussion of the problem remains a serious part of this story.

The controversy remains: the Tanzania government wants to evict 40,000 Maasai from traditional lands to increase a hunting concession for Dubai businessmen and princes.

The error so many of us participated in last May was reporting the controversy as an immediate crisis.

And that escalation of reportage has worsened. Respectable media reported today that the evictions have already begun. They haven’t.

We were led to our mistakes last May by the organizers of a very successful petition campaign on behalf of the Maasai, which has exceeded its wildest expectations by the way.

In May the organizers of the petition broadcast an urgent appeal for signatures based on an exaggerated claim that the government was imminently prepared to forcibly oust the Maasai.

Several of my readers pointed out to me this wasn’t true. The problem was real – and continues – but the immediacy was overstated and the government had set no deadline for forced eviction.

The situation is the same today.

Numerous legal maneuvers have been going on in Tanzania for some time, long before the petition campaign began. These continue today.

This past weekend, a report in London’s Guardian attributed to another report from Survival International elicited comments from the organizer of the petition which were exaggerated and went viral.

The story even emerged as a headliner in America’s normally very careful electronic media, Salon.

This is a complicated and serious story, and the media (including at first, me) just doesn’t seem to know how to handle it correctly.

Survival International, in fact, has a good time line of the real story. Click here.

The government’s policy came to the fore five years ago. There have been ups and downs, and based on today’s useless meeting in Dodoma, I’d say the government is losing the battle of waiting it out, and that’s good.

And it’s so good that many of my readers and others worldwide have signed the petition. But like a previously exaggerated social meeting campaign, Save the Serengeti, the movement starts to become more important than the issue.

Save the Serengeti absolutely contributed to stopping the building of the Serengeti highway (when it was in its first iteration, Stop the Serengeti Highway) but in no way alone despite its self-promoted appearances. Moreover, when building the highway was stopped, the campaign didn’t.

The real development of this Maasai story is simpler. Under increasing pressure to abandon once and for all the government’s policy to evict the Maasai from Loliondo, the government has offered a cash payment in compensation to 40,000 Maasai.

The offer is for approximately two-thirds of a million dollars or about $15 per person evicted, in addition to previous offers of new land that theoretically equals or exceeds the land that would be confiscated.

Today’s meeting in Dodoma was to discuss this new offer, and as expected, Maasai leaders rejected it.

Undoubtedly this new emergence of the controversy benefits the Maasai, and that’s good, too. It’s just not … well, exactly right to think of it as immediate to this prolonged problem.

Meetings occur all the time between government officials and Loliondo Maasai. Ridiculous moves like $15 per Maasai evicted should hardly be considered starting new or more serious confrontations.

Yet even in Arusha some thought so. Last night an arsonist started a terrible fire in Arusha that caused some to wonder if it was in protest of the Dodoma meeting about the Maasai eviction.

I received several requests to write this blog. I’m extremely thankful for my readers’ sensitivities to this problem. I’m glad that we’re all “on the side” of those benefiting from the exaggeration of the problem.

But ultimately it’s the facts that matter. It’s the facts we need to be vigilant about, not the hysteria.

The Kisiel family’s last two days on safari featured the great migration at its best, including a croc feast of a wildebeest river crossing.

The Kisiel family’s last two days on safari featured the great migration at its best, including a croc feast of a wildebeest river crossing.

We expected to find the migration in the north, and we did. We flew from the central Serengeti into the far northern Serengeti landing virtually in sight of the Kenyan border. Although our lovely Kuria Hills tented lodge was a half hour south of here, we spent most of the time game viewing in the north.

Five minutes after we left the airstrip in the Mara Region of northern Tanzania we were skirting the south and west banks of the great Mara river. Crocs so big I call them “dinosaur crocs” were everywhere, waiting for one of the two meals they eat each year.

We saw one monster that John Kohnstamm said was 24 feet long. Close. But on that first day, no wildebeest near the river that we could find. So we headed south to camp through absolutely beautiful Mara grasslands and rolling hills.

That afternoon we saw our first oribi, not something many safaris see. It’s a gorgeous little, somewhat hyper antelope with large black face spots.

We also saw a number of wonderful birds in addition to the common headliners like the lilac breasted roller. Add the gorgeous cliff chat, rosy-breasted lark, perhaps a hundred red-cheeked cordon bleu among many others.

The next morning – the Kisiel Family’s last morning – we packed a picnic lunch and left before dawn.

We stopped on a ridge that looked north into Kenya and waited for the African sunrise. We had flushed out many square-tailed nightjars having listened to their woeful scream in the night. Then about ten minutes before dawn the omnipresent ring-necked dove began to fill the veld from horizon to horizon with its hypnotic song.

And then a few minutes before sunrise the whole veld exploded with bird song, and Africa’s giant sun peaked up blaring a perfect red-orange orb through the thick morning haze.

We traveled all the way past the southern Sand River border of Kenya and began searching along the Sand River. There we saw what will always be one of my most precious safari events.

We were driving somewhat hidden in the heavy bush at the top of the 15-foot embankment of the Sand River, which unlike the Mara, usually has an all sand bottom with good and copious amounts of water flowing under the sand.

But there has been so much rain that there were actual streams in the sand river bottom.

We came upon a lion pride eating a recently killed wildebeest. There were two lionesses with seven cubs in two different litters, plus a young and magnificent pridemaster, plus a slightly younger juvenile male that already was bigger than Mom and was sprouting a wonderful new mane.

What was specially interesting was the fighting that we watched between Mom and this juvenile male. She would not let him eat.

He could easily have whooped her, since he was bigger and stronger, but her motherly instincts knew it was time for him to be kicked out of the pride. Not too long before we had seen two other males about his age, sulking on an anthill starving as a ring of wildebeest surrounded them.

Young males don’t know how to hunt. They have to teach themselves, and if they don’t, they starve. It’s the reason there are more females in the overall lion population than males.

So the juvenile male that had somehow managed to stay with the pride was trying a new tact. But it wasn’t working.

Any move he’d make, even the slowest and most methodical attempt to raise his leg on the embankment to scoot away, and Mom would snarl and attack him. Finally, he slipped away.

We had seen in about twenty minutes what wildlife photographers take years to document.

But believe it or not, the best was yet to come.

Thinking we’d seen it all, sated with experiences, we began to head home along the river. Lo and behold there was a small group of wildebeest and zebra that looked like they were ready to cross the great Mara River.

And below them, to the right and left and side and bottom, were giant crocs waiting. They were steady in the water despite the strong current, or on the embankment, or on the island rocks, just waiting … waiting.

So… we did, too.

Roy Stockwell kept saying to the wilde across the river, “Come ‘on guys, the grass is much sweeter on this side!”

Whether it was Roy or not, they finally came, in a sudden leap from the bank followed by leaps across the great river.

The crocs moved in from every side. One dinosaur sailed straight for a calve and pulled it under and another on the other side took down a yearling.

Both started screaming and the mother of the calve turned around and jumped back in the river, literally pouncing on top of the croc, but it was no use. He took it under and she leaped exhausted back onto the shore.

The larger yearling drew many big crocs as they started vying among themselves for the feast.

Camden Reiss, like many many kids and adults as well, didn’t like what he saw. And it is a terrible moment, and yet when we as the real king of the beasts step back to let nature do her thing, we realize there are as many wonders as catastrophes.

“Can’t get better than this!” Grandpa shouted.

At Seronera for two days we were engulfed by part of the wildebeest migration, something totally unexpected.

At Seronera for two days we were engulfed by part of the wildebeest migration, something totally unexpected.

Historically the wildebeest would be much further north by late June/early July, and the reports out of Kenya were that they were. In fact, the crossing of the Sand River from Tanzania to Kenya was reported in early May.

But here we were, 120 miles further south, surrounded by wildebeest and zebra day and night. The saturation of the herds on the veld extended from just south of our camp at the northern end of Rongai, just south of Mawe Meupe and north to the western corridor junction road.

The western portion was bordered by the Moru Kopjes and the eastern portion ended before the Maasai kopjes.

It’s very hard to estimate the numbers but I’d guess between 50,000 and 100,000 animals, or about one-fiftieth to one-twenty-fifth of the entire population of zebra and wildebeest in the Serengeti/Ngorongoro/Mara ecosystem. Where were the others, the 2+ million?

All accounts suggested they were well into Kenya and that they had moved there quickly and densely through the eastern edge of the Serengeti. But numbers like this are hard to grasp, particularly if the veld is the least broken by hills or forests.

All accounts suggested they were well into Kenya and that they had moved there quickly and densely through the eastern edge of the Serengeti. But numbers like this are hard to grasp, particularly if the veld is the least broken by hills or forests.

In effect that small fraction of the wildebeest was a grand migration for us, and it wasn’t at all expected. Late and heavy rains has made the entire veld from Seronera north green. On our charter flight today to the border with Kenya, there was hardly a piece of land that wasn’t green.

Unlike birds, animal migrations are triggered strictly by food. If the food source is good, as it apparently was for the tale end of the great migration this year, they will linger and stay behind.

During our two days in the area we also saw two dozen lion, a hundred or more elephant, a leopard with a new kill in a tree, countless hyaena and many defassa waterbuck and hartebeest. We traveled south into the Moru Kopjes and saw little game but enjoyed the sacred stories of the Maasai at Ngong Rock and the morani cave paintings.

Seronera has always been an exceptional place for game viewing, but as a tourist you’ll pay handsomely for it, and not in dollars. It’s very crowded. At each sighting of a lion or leopard there could easily be 20 cars.

We have enjoyed a safari so far in remote and beautiful places with good game viewing and very few other cars. But it’s impossible to do this in Seronera, and I personally feel Seronera should not be missed.

The wilderness today in Africa has been saved by tourism. Seronera represents a core of intense game viewing with a multitude of accommodation alternatives. One positive way to look at it is that no one would have the opportunity of visiting any part of the Serengeti if the revenue received from visitors going to Seronera weren’t included.

The Seronera river valley is where we saw a dramatic half hour scene of 3-400 zebra cautiously drinking from the river then exploding out when the least sign of danger was sensed. Only here in the central Serengeti is a river system large enough to attract so many resident animals.

It’s also a reality check. Lion ignore us in the remote Kusini Plains where there’s no other vehicles but our own. But they come from generations of animals that have been habituated to cars, principally in places like Seronera.

So I wouldn’t exclude Seronera from an itinerary, and that attitude is what allowed us to truly experience the great migration when it had neither been expected or promised. That was luck, certainly explained in part by climate change, but mostly by where the extended rains fell.

And it seemed they fell right on our camp just before we arrived!

On safari: Serengeti Dust Storm

On safari: Serengeti Dust Storm

A terrific dust storm swooped down from the crater highlands onto the Serengeti aborting our plans to visit a number of sights on the southeastern plains.

One of my personally most favorite days on safari is when we leave Ngorongoro for the Serengeti. Whether it’s during the rainy season when we’ll travel through hundreds of thousands of animals, or the dry season when the dusty plains reveal fascinating secrets, it’s hard to beat.

I normally stop just after the crater rim to demonstrate the symbiotic evolution of the giraffe and the whistling thorn tree, then my exciting lecture on early man at Olduvai Gorge, then the mysterious walking hills of the Shifting Sands.

And then the immense seemingly endless Lemuta plains with views you can’t imagine.

So yesterday we struggled out of the cars on the crater rim walking to a grove of whistling thorns against a gale force wind. It wasn’t just that it was cold, it was so strong.

When we arrived shortly thereafter at Olduvai I knew I’d have to rethink the day. The wind was at least 40mph and the dust was obscuring everything. The gorge and the museum were packed solid with visitors, so we decided to leave early.

At Shifting Sands the dust was so bad that Sophi and Hadley, the two teenage girls, wouldn’t leave the vehicles, and that was my sign that the day had to be replaced.

It wasn’t that I was worried we’d get lost in the dust, but there were no views, and it was near impossible to open your mouth without being filled with dust no matter what direction you turned.

So we turned back to the main road and regrouped. It was tough to give the day up, because the storm ended at the main road, confined it seemed to the eastern half of the Serengeti. But we continued to our lodge at Ndutu, arriving 5 hours early but to a very welcoming staff, clear air and cold beer!

On the impromptu afternoon game drive we saw the Masek pride of lions which included three sets of cubs, the youngest about six weeks old. I really wonder in this start of the dry season if those cubs will make it.

We then watched a puff adder wiggle across the entire lake bed of Masek! It was accompanied by double-banded coursers and an immature augur buzzard I presume making sure it didn’t go astray.

This morning we headed out to find cheetah, and boy did we! Two young adult brothers gave us every angle of pose and then jumped on the car where the kids were! College sophomore Jeffrey was right up there popped through the raised roof to photograph its every whisker!

“Good Godfrey!” Grandpa Mark exclaimed. “It can’t get better than this!”

We then watched a larger female cheetah on a failed hunt of Thompson’s gazelle. Only about 20% of cat hunts are successful, but even so it was exciting.

It’s extremely dry around Ndutu where we currently are. On our trek to Hidden Valley I was surprised there wasn’t a drop of water left. And yet the grasses are still a little bit green. It must be the dry, cold wind.

We now head north for two nights in the central Serengeti before two nights in the far north, where I expect it will be greener and filled with animals. So stay tuned! But I’m leaving internet availability so it may be several extra days before I can let you know what happened.

Dear Grace & Other Careful Readers

Thanks. This blog is in error. The “petition site” (automatically) contacted me (their deadline for the petition is next week, June 1, 2014) and fed me the links that I took to be current. Fellow bloggers did the same and we contributed to each other’s errors. All the news below is one year old. As far as we know the eviction process is on hold as a result of a suit filed by Maasai leaders which is still alive in the Tanzanian courts.

Petition site organizers believe if they reach 34,000 signatures by June 1, 2014, they will continue the pressure needed to keep the evictions on hold, so please proceed reading and sign the petition. But my apologies to all my readers for syncing off by a year.

– Jim Heck

Desperately needed: your signature on and broadcast of a petition to stop Tanzania from giving away part of the Serengeti to Mideast princes.

Sign this petition and circulate it, now, now. We have little time.

Last year I reported that Tanzania President Kikwete announced that he was going to evict 30,000 Maasai from their homeland in Loliondo in northern Tanzania to enlarge an existing hunting preserve owned by potentates in Dubai and Jordan.

As with the stopped Serengeti Highway, the outcry was substantial, especially locally from the Maasai. Nothing more happened. Until now.

Presuming the resistance had died out, Kikwete announced last week the sale was going ahead.

Manipulating Tanzania’s incredibly corrupt laws, Kikwete has decided to designate this area as a “wildlife corridor” which allows hunting but forces the eviction of the Maasai.

Don’t be fooled by this sinister sobriquet. Kikwete and past Tanzanian presidents have close relationships with Mideast potentates, where most of these old politicians’ money is stashed.

This is a land grab if ever there were one.

And this time the impact is actually less on conservationists and tourists than on local Tanzanians.

“My people’s livelihood depends on livestock totally,” a prominent Maasai politician, Daniel Ngoitiko, told the Guardian. “We will die if we don’t have land to graze.”

And don’t think this means there’s a bunch of dirty nomads running around half naked chasing dying cattle. Loliondo has become an important agricultural hub for Tanzania. We’re talking about modern ranching.

Ngoitiko’s comments could just as easily be said word-for-word by any Texas rancher afraid of a government land grab.

I’m infuriated by Kikwete’s dictatorial stance on this, his total disregard for the Maasai community which is trying so hard and doing so well to modernize.

So just as they begin modern farming techniques, he drives a stake through their back forty. There’s everything in his actions to suggest he’d rather send the Maasai back to the Stone Age than help them develop.

Ngoitiko told the Guardian, “We will fight against it until the last person is gone,” he said. More than fifty local Maasai officials said they will resign if the move goes through, effectively leaving a huge area without any local governance.

In an incredibly condescending dismissal Tanzania’s minister for natural resources and tourism, Khamis Kagasheki, was then quoted in the Guardian article as saying: “If the civic leaders want to resign, they can go ahead. There is no government in the world that can just let an area so important to conservation to be wasted away by overgrazing.”

This is equally a blow to the Serengeti, which the area is contiguous with. It’s a wedge between Kenya’s beautifully protected Maasai Mara and the Serengeti National Park.

Inserting hunting this far into the area could disrupt normal wildlife behaviors.

Please help. Sign the petition and circulate far and wide.

The safari calendar in East Africa resets each year at the end of November, and the news that has poured in from our safaris just keeps getting better and better. 2014 may be an exceptionally outstanding year for safaris!

The latest bit came from safari traveler Loren Smith traveling on a safari EWT arranged for the Cleveland Zoological Society. You can see Loren’s fabulous video above.

The first is the only disturbing one: there continue to be too many elephants, but let me get that single negative out quickly. I’ve been warning of a growing elephant conflict for more than a decade in East Africa. My blogs are replete with the problems and endless attempts at solutions.

The “elephant problem” has become a political problem in East Africa. Candidates for political office in both Kenya and Tanzania now often have planks in their platform regarding what to do about elephants.

My concern is that there will be overreach. And as I’ve often written, the exaggeration and bad analysis of the elephant poaching problem in the west isn’t helping.

But I can assure you that on safari the effect is nothing less than exhilarating as you can tell from Loren’s video. I show minute:second time points below in the video corresponding to my remarks:

0:10

Loren traveled in the last half of February, which over the last forty years of good climate statistics suggests should be much drier than shown in his first shots in Arusha National Park.

Typically the entire first half of the year is a wet season in northern Tanzania, but in February the precipitation abates at times almost completely. If you were planning your trip strictly by statistics, Loren’s video would have had little green in it.

Global warming has been changing this steadily for almost a decade, and as you can see by the green bushes, it’s not dry.

It’s hard for animals to be affected negatively by too much rain. But it definitely affects people, and that’s been one of the continuing stories in the equatorial regions of the planet as global warming progresses.

0:45

Tarangire is bit drier, which is always the case. Arusha is the wilderness around Africa’s 5th highest mountain and when it’s wet, it’s always wetter there. Tarangire is actually an ecosystem more similar to southern Africa than East Africa and is the only northern Tanzanian wilderness defined by a sand river ecology.

1:04

This lady has just eaten and washed herself off, which is why she is so close to the water in Silale Swamp. We can speculate about the three new lacerations on her hide. Two are just above her left hip and if you watch closely you’ll actually see a larger one on the far backside, middle of her left hip.

Lions gorge themselves when eating. Their very inferior molars are almost useless. They don’t chew much. They tear and swallow huge hunks of meat. A 400-pound male lion can easily chow down 70 pounds in a sitting. That extends the belly and makes it droop and is often confused in females as being pregnant.

So what caused the problem? We can only speculate but I think she was in a tussle with hyaenas, and the lacerations are the hyaena nips. In this area of the Silale Swamp there are four very grand males and for some reason they aren’t very welcoming of females. It could also have been a fight with the males.

Tarangire is actually where I think the best elephant experiences should be had, but Loren obviously had a fabulous one at nearby Lake Manyara National Park!

1:33

Notice the small tusks on this elephant, the legacy of the horrible years of elephant poaching in the 1970s and 1980s. As the video progresses we’ll see some better and longer tusks, because the elephant population is definitely on the increase and growing healthier.

Manyara was where the very first substantial elephant research was carried out in the 1950s by the famous Ian Douglas Hamilton. In those days there was no place on earth with as many and as healthy elephants as Manyara.

3:18

Junior here has a short branch in the back of his mouth. Elephant get a new set of molars about every ten years and like all good kids, he’s got to massage those tender gums!

4:36

What we see in Loren’s video is a large mass of transitory elephants: they’re moving through Manyara. They don’t live here as Hamilton’s elephants did in the last century. You can tell this by the way many multiple families are grouped together.

In a totally calm and balanced system, elephant families tend not to group. But when they’re on the move they do.

Tarangire provides a massive corridor to elephants south into central Tanzania’s great wildernesses of Ruaha and Rukwa. They move northwest from Tarangire into Manyara, and from Manyara they moved in very narrow corridors into Ngorongoro where they can then spread out widely into the Serengeti and Mara.

It isn’t that elephant are breeding so rapidly that their numbers are bulging. Poaching has been on the increase and the growth rate of the population is not high. But human encroachment is on a rapid increase, so their habitat is shrinking.

And more than ever, they have to move. Loren’s video is a magnificent documentary of this.

6:12

Until recently Ngorongoro Crater had the highest density of lion in Africa, but we need new studies since the rapid decline in lion was documented a few years ago. Even so, it is probably still one of the best places on earth to see lion.

These are two juvenile males, and despite their bravado they’re having a hard time. Look at their bellies and then look at their muddy feet. Lion like cats all over hate water.

Something was in the marsh that seemed like easy pickings, but they even missed that.

In a balanced population in the wild there are many fewer males than female lions. This is because so many young juveniles like these die of starvation. Unlike the sisters in their litter, they aren’t taught to hunt by the mothers.

But also unlike their sisters who usually remain with the mothers, the males are kicked out before they’re fully mature. A fully mature male is 50% bigger than a female, and nature’s way among lions to avoid inbreeding is to kick out the teenage males before they get as big as mom.

They have to teach themselves to hunt. Obviously enough learn, but these kids don’t seem to be doing so well. You might think what a pretty mane the one has. What I notice is their ribs and boney haunches. When the one starts to call, I think that’s a real hunger pain or possibly a pointless message to Mom for help.

7:50

The video ends in the central Serengeti and notice how wet the track is. Good for the critters to be sure. Not so good for the farmers.

Thanks Loren for an outstanding quick story of Tanzania’s wilderness in 2014!

The rains have come back to the Serengeti; the wildebeest are moving south; all is well.

The rains have come back to the Serengeti; the wildebeest are moving south; all is well.

Last month the travel media went ballistic worrying that the wildebeest migration had been historically altered from eons of pattern and was going to spend the season in Kenya, when they should be in Tanzania.

The rains were late … well, maybe 3-4 weeks late. And there were plenty of YouTube videos and blogs documenting large groups of wildebeest moving north over the Sand, Mara and Balaganjwe rivers, when they should have been moving south.

Well, they’re back on track now.

“Wildebeest on a southerly course,” writes the very respected tour company, Nomads, yesterday. Their blog continued:

“There has been rain in the crater area towards Endulen, Central Serengeti, some in Ndutu and even in Loliondo so we are hoping for the plains to be green soon and the movement to proceed southwards, and by the time Christmas comes they should hopefully all be where they should be.”

And the weather report for the Serengeti is all but boringly normal.

This is tedious.

Whether it is the wildebeest migration, the coming apocalypse or the conversion of Obama as a mullah in Iran, our current world of instant communication takes the least bit of misinformation and spreads it around the world as the gospel truth.

A month ago, travel professionals were lamenting the end of the Serengeti migration. Yes, the rains may have been late, if 3 or 4 weeks is late in today’s crazy climate change world, and what do you expect a half million animals that have to eat grass to do?

They went where it was raining, and that was – for a short period of time – in an opposite direction from the norm.

How has your weather been recently?

But it’s been a very short time that the weather was out of sync in the Serengeti, a very short turnabout, and they’re back on track. And even if it had been longer, it would hardly have been the “end of the migration.”

We’re all adjusting at home and abroad to changing weather. And so are the wildebeest. And for us travel professionals it means certain caution about promising anything that has to do with weather.

But don’t worry about the wildebeest. They’re extremely adaptable.

Which is a lot more than I can say for most travel professionals.

Snapshot Serengeti is working masterfully, and not just to help the science of the Serengeti but to unmask once and for all the increasing fraud of quasi tour experiences purporting to need the traveler to accomplish some scientific or cultural mission.

Snapshot Serengeti is working masterfully, and not just to help the science of the Serengeti but to unmask once and for all the increasing fraud of quasi tour experiences purporting to need the traveler to accomplish some scientific or cultural mission.

A plethora of tour companies selling travel experiences supposedly to help usually unqualified researchers or exotic project managers will never satisfy consumers’ demand to validate their experience by other than just enjoying or learning.

That’s often perplexed me. Curiosity should be enough to motivate travel. A good guide can in 20 minutes convey, inspire and make memorable a foreign experience a thousand times more successfully than a poorly fed grad student desperate to create a published study.

Indeed, learning first-hand is an even greater motivation to travel, and to be sure there are times that without actual participation in the mechanics of a situation, the understanding is scant. But as I’ve often written, that scant understanding is worth it, and attempts at full understanding by volunteering is usually compromised entirely by the amount of time the volunteer is willing to give.

EarthWatch is usually the single exception, particularly in Africa, but it is not always so. WorldTeach, International Volunteer, Cross Cultural Solutions and Full Center are examples of basically well marketed tour companies purporting to do good work abroad by organizing short vacations towards “giving” rather than “receiving.” And they are basically frauds, doing little good other than satisfying the guilt of travelers and building the equity of their companies.

In many many ways, they are identical to the tens of thousands of small church missions with very dedicated volunteers whose projects are tenuous as best, destructive more often, and usually producing a very bad culture of dependency.

But in addition to the early EarthWatch programs and a core of good ones the organization produces regularly, there really isn’t another pay-to-volunteer experience in Africa worth commending. Until now.

Snapshot Serengeti is brilliant.

The dean of African lion research, Craig Packer painted himself into the inevitable researcher’s basement of too much data. Like so many scientific projects, as money is raised for a goal it’s spent immediately, so Packer raised the money for 225 robotic cameras throughout the Serengeti that were motion or heat triggered.

The goal was to acquire so much definitive research about the whereabouts of various species throughout the year, that a truly definitive study of the Serengeti’s very fluid ecosystem, driven primarily by the great wildebeest migration, could be started.

But suddenly the study had 4.5 million photos, certainly enough to reach some at least initial conclusions, but no way to digest such voluminous data.

Nor has Google Recognition achieved the ability to distinguish between a topi and a hartebeest at 100 meters from less than a high quality lens.

Zooinverse to the rescue: “Real Science OnLine”

And yes, you can actually make a difference. And it doesn’t cost anything.

Packer using Zooniverse signed up 15,000 volunteers (in ten days) on line who felt they could identify African animals. A few, more qualified programmers wrote an algorithm created from the initial detailed study of volunteers to determine the likelihood that the identification is correct.

So by giving a certain multiple number of individuals the same packet of photos to identify, and correlating their answers with the algorithm specifically created for this specialist project, real data is mined at phenomenal speed.

In fact so fast, that the cameras are having a hard time keeping up with the refined results produced from the volunteers.

This works. There’s no fraud involved, and everyone involved can be assured that what they’re doing has real scientific value.

Congratulations to the InfoAge, the Serengeti Lion Project and Zooinverse!

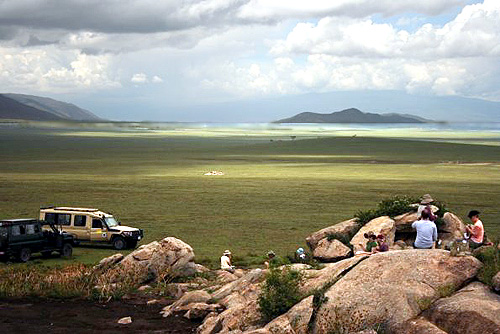

If you haven’t visited the spectacular Soroi Lodge in the Serengeti yet, you better do so soon, because I don’t think it’s going to be around for a very long time.

If you haven’t visited the spectacular Soroi Lodge in the Serengeti yet, you better do so soon, because I don’t think it’s going to be around for a very long time.

The story of Soroi Serengeti Lodge is the story of investment in African safari lodges virtually from the onset of safari travel in the 1960s.

It’s the story of small business trying to cash out quickly on trends, and then always, failing. Only now, as Africa develops its own safari traveler are things looking up … but not for the likes of Soroi Lodge.

Below is my detailed review of Soroi. I stayed there while guiding the Felsenthal Family at the beginning of July for two nights. On Thursday, I’ll generalize in this blog to what’s happening throughout Africa with its lodge investment, tell you which few investors are doing the right thing and why, and what warning signs we’re now getting for the mid-term for safari travel.

Set about half way between Serena Lodge and the Grumeti airstrip in the southern half of the western corridor, Soroi is one of the most beautiful middle-sized lodges I’ve ever stayed at. The design avoids the cliche of avant garde but is creatively modern with lots of angular twists and turns, multiple levels and daring concepts like putting a pool next to the bar and lounge.

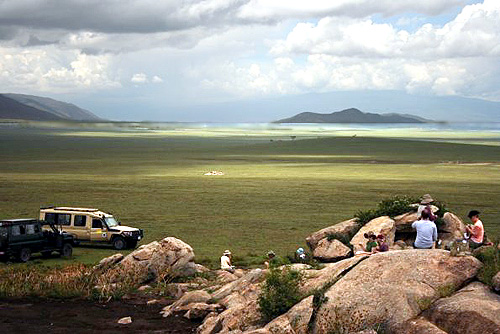

Some of this is probably mandated by its limited space, the top of a 600′ high hill 25 kilometers off the nearest road, resulting in an absolutely fantastic and intimate view of the grande dame of African wildernesses.

Some of this is probably mandated by its limited space, the top of a 600′ high hill 25 kilometers off the nearest road, resulting in an absolutely fantastic and intimate view of the grande dame of African wildernesses.

The 25 thatched cottages and suites are connected by long and sometimes meandering walkways like trestles through outer space, views everywhere.

The bathrooms are about the same size as the bedrooms, which are adequate and heavily wooded, and the piece de resistance is that massive deck overlooking the Serengeti. I estimate the view from the deck stretches at least 35 miles over the Serengeti. There are no other lodges and only one track in this immense area, fulfilling every safari traveler’s dream of being alone in the remote beauty of Africa.

And that’s it folks.

Hardly two years old, this artistic masterpiece is already not working.

Much of the room finishings are breaking off. The thick lustrous wooden stain is already down to the bare wood in the bathroom and there is already significant corrosion on all the brass plated fixtures. The patio doors between the room and the deck no longer close well, leaving a gap for you know what … bugs. The screen meshes on the perfectly designed canvass windows are buckling and tearing.

There is no communication between the distant cottages or reception and management: no phones, no walkie talkies as is often customary. So there is no way to communicate danger, other than a pitifully small whistle attached your key chain, and yes there could be danger. I spotted lion and hyaena tracks regularly on the walk from my room.

There is a bouquet basket of teas and coffees, sugars and sweeteners framed by two lovely china cups on the rather small writing desk in your room, but no tea or coffee maker, and the only way to use them is to order hot water. Staff deliver hot water on demand, but there is no way to order it except to walk up to reception – might as well get it yourself.

And even that is complicated by the lodge edict that you can’t walk around at night by yourself. I learned from an askari who claimed to shoo the lions away every night. But there is no way to call for an askari at night … except your whistle.

And consider the beautiful and large four claw bathtub elegantly described in much of the lodge’s promotional literature. The briefing we got when arriving explained that there wasn’t enough hot water to fill the bath more than … maybe, once. So … don’t use.

Laundry is something that every African safari lodge and camp provides, albeit at various costs from free to outlandish. Soroi’s website and its information packet describes that two pieces of laundry are free and additional will be charged.

But at the briefing we were told there couldn’t be more than two pieces accepted, at any charge. And the complicated maize that management has thrown up to us weary warriors in need of a clean T-shirt included the fact that laundry is only accepted at night, for return the following night. This is exactly half-cycled from what is common virtually everywhere else, morning to that same evening, which further complicated anyone’s laundry plans particularly if they were only staying for two nights.

One of the six rooms my group was assigned didn’t have enough water to flush a toilet.

And my three drivers apologized to me the night after we arrived that they weren’t allowed any water to wash the vehicles.

So what do we have? We have a lodge that doesn’t have enough water, which has not been built to last, and which is declining fast. An investment with a quick R.O.I.

It’s a lovely sand castle, but the engineering won’t withstand the next strong wind.

This beautiful, very artistic but so temporal investment is the perfect example of why investment in African safari lodges is so tricky, and probably so misplaced.

Children really do better than their parents on a family safari in all cases, no matter how difficult or how easy it might be. And that makes sense.

Children really do better than their parents on a family safari in all cases, no matter how difficult or how easy it might be. And that makes sense.

The first question I get from a parent or grandparent considering taking their family on safari is what is the ideal age, or actually more often, what is too young to go?

The Felsenthal Family Safari organized by Babu Eddie just ended, and as I reflect on that ten days a lot of the answers I’ve given over the years are confirmed.

Children of virtually any age are as different as any person of any age, so the qualification that my generalization might not apply to your particular child is a very important one. I’ve had three-year-olds that two decades later would recite the days on safari with rapture. And I’ve had many repeat adult clients that for the life of them couldn’t remember what they’d done before.

But generalize I will. The best ages for children on safari are between 8 and 16. The Felsenthals had a 5-year-old and two 7-year-olds and the safari worked well. And last year I guided a family with university students, and they were outstanding safari travelers.

But in general kids under 8 lack the stamina a safari requires, and kids over 16 lack any interest for much except being home with their friends.

How this generalization was torn to smithereens by the Felsenthals! To begin with, I was amazed at how much they wanted to do as a family. With near unanimity the family pressed the envelope of reasonable game driving. According to my notes, we had four game drives of 12 hours!

And quite a few of ten!

Part of this was because a family safari usually does better with all-day drives with a picnic lunch, than with the traditional early morning and late afternoon drives separated by a long mid-day period in camp with lunch.

It’s easier for a family to get going in full light and without an early wakeup. But in my memory I don’t remember such enthusiasm as the Felsenthals.

We were unable to get satisfactory accommodation near the expected whereabouts of the migration in northern Tanzania, and that became the motivation for the 12-hour day. We left the central Serengeti around 7 a.m. and traveled to the Kenyan border, returning around 7 p.m.

And … we found the migration! Big time, in fact. It was a relief to me, of course, and the family was fully aware that the information we had garnered might not have been accurate. But as it turned out, it was.

And on the way back, 7-year-old Nate simply fell asleep on the back seat of the cruiser, certainly the most bumpy part of the car!

I was amazed day after day how these young kids all chose to go out for hours longer than the average adult safari. But then I’d learned long ago that the stress of such a long day really hangs on the parents, not the kids.

They are understandably worried that such a trial of bumpy roads and long periods of seeing nothing foments the boredom that often turns into anxiety or peevishness in kids. But it doesn’t. And my saying so from experience after experience doesn’t seem to convince anyone.

But it doesn’t. Kids always … and I mean always … end up doing better than their parents on safari, and particularly when the safari is challenged by long drives and bumpy roads.

That isn’t to say they’re constantly enthused and wrapped in attention. It just means that the parents do more poorly than they do.

So the maxim stands: analyze your own stamina and interest, parents and grandparents, as the threshold of what the family safari should do. The kids will always work into it just fine!

I can’t thank the Felsenthals enough for giving me such a fine experience, too! Our elephant encounters in Tarangire were exceptional and so exciting. There was even a trunk into the pop-top roof!

In one morning around Seronera, we saw four leopard and twelve lion. Not to mention several hundred zebra, and a giant croc guarding its zebra kill.

We found the migration, a beautiful and always awe inspiring site. And as usual with migration experiences, there was something extremely unusual and dramatic: we saw at least four hundred vultures collected together near a bit of water drying their wings.

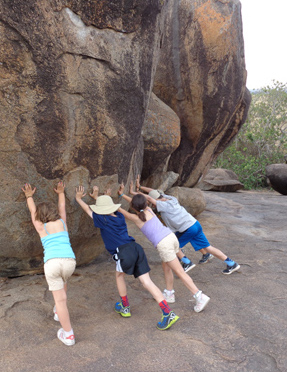

The Felsenthal kids spent a good hour or two mingling with school kids from Arusha on a field trip safari, and taught them tic-tac-toe! The Felsenthal boys played frisby on the endless plains of Lemuta, not another car in sight for 50 miles, even as a single Maasai teenager walked across this enormous veld to greet us.

We saw hyaena relocating babies that couldn’t have been more than a day old. We watched a family of lion unsuccessfully hunt warthog that successfully held up backwards into a hole!

We walked around the actual place where Zinj, the Nutcracker Man, was found, and walked over the Shifting Sands hills that themselves walk over the veld. The kids pounded the magical Ngong Rock with granite stones to recreate the dream booms that called Maasai to their last conclave in 1972.

And for icing on the cake, hardly a half hour before we took off on the charter that started the journey home, a lionness flopped in the shade of the kids’ safari car!

There’s just nothing as good as a family safari. And no one as happy as the kids!

The Botswana government confirmed today that President Ian Khama had been scratched by a cheetah and had received several stitches in his face. Not a wild cheetah, but a caged cheetah that the president was obviously observing, and nothing serious enough to announce it until the press asked about it, today.

And it probably wasn’t even intentional. Cheetah differ from other cats in that their claws can’t retract.

Cheetah are interacting with tourists (and presidents) more and more. In each of the last two years I’ve had cheetah jump on our car to the terror and delight of my clients.

Earlier this year as we were approaching the edge of the migration in the Serengeti, we encountered a family of four cheetah: big mama looking somewhat weary at her three terrible teens: three 6½-month old not-quite-cubs-any-longer.

Because cheetah are the most harassed of all the cats in the wild, they love anything that doesn’t try to eat them … like tourists. I suspect, though, that if there were another animal in the wild except man that didn’t bother and pester them, they’d come purring over like a lap cat with affection.

Cheetah eat faster than any other cat, because if they don’t, they’ll have the food taken away … by bigger cats like lion and leopard, by hyaena, even by jackal and big birds. It’s a stressful life.

So when something just comes along to look at them, they’re most accommodating if not presumably relaxed by the notion that a man – the greatest hunter and threat to all living things – wants to be its friend!

After all, the enemy of my enemy is my friend, right?

Not to mention that a car is pretty high off the flat veld. Jump up on it and you’ll achieve a view far superior to that stumpy little termite mound.

All cats display innate curiosities, particularly as cubs, so when our vehicle stopped at the edge of the migration to watch the antics of the family of four cheetah last March, they were distracted to watch us.

With a head cocked unnaturally to the side of a slithering body that moved sideways around the front of my car, Number One opened his mouth in his pitiful little hiss, stopped, sat down on his haunches and then jumped up on the hood.

Numbers Two and Three meanwhile jumped on the two tires mounted on the backside. And yes, the roof was up and open!

Cheetah began this behavior years ago in all the national parks and reserves where they were protected. As tourism increased driver/guides naturally would try to encourage cheetah onto their car, for the obvious thrill it provides the client.

Rangers and scientists then complained that the growing number of cars around cheetah were disrupting their hunts, and guests should stay well away from them.

This was – at the time, and now – balderdash. I have no doubt that there were hunts disrupted, and we should be extremely mindful of not approaching cheetah on the hunt, but my experience has always been that in the vast majority of situations driver/guides do not disrupt hunts. It’s much more rewarding for a client to see a cheetah hunt than a cheetah tail.

Rather, it was just rangers and scientists pining for the good ole days when everything was pristine and wild. I think that was in the Pleistocene.

In our case, we were the only cars we’d seen the entire morning, and we were in a very, very remote area of the Serengeti. We had four cars, and as soon as the cheetah jumped on mine, the others stayed back.

Number One began admiring himself in my rear view mirror. I could easily have touched him, but everyone – cheetahs and tourists – were having such a grand time I didn’t want to disturb them.

Like cat cubs anywhere, the three of them were suddenly all over the roof, the hood, the tires, tumbling and not quite as sure footed as the mother who had run away and was calling them to no avail.

As Number Two decided to tightrope from the backside under the opened roof to the front, and tottered a bit, there were audible gasps from my clients.

All well and good, until Number Three decided to chew apart the rubber lining we put between the roof and the top edge of the car, to seal the roof when it’s pulled closed. And this was the rainy season and I fully expected the afternoon shower later in the day.

So that did it. I hissed back, and he hissed at me while Number One started to eat our radio antennae. At that point I started shouting and waving my hat and everything else I could find, and finally, reluctantly, the three kids jumped off the car.

This is always the easiest time of the year to find the largest single migratory group of wildebeest. It’s never the most dramatic time (which is the river crossings later on), but I prefer now because you see so many more animals.

And because there are so many babies. In fact, the herd has suddenly grown a quarter larger as nearly every mature female calves.

And set on a veld that is so spectacularly lush and colored by multitudes of wild flowers, it’s hard not to understand why this is my favorite time.

Nevertheless, finding “the migration” (which means a significantly large portion in one group) is not as easy as it seems.

The animals move with the most nutrient grasses, which grow where it rains. So finding the migration is as easy as exactly predicting the weather!

But we had intelligence that placed the migration in the Gol Kopjes, north of Naabi Hill. That in itself was a bit unusual, tad too far north and east for this time of the year. But clearly they were not around Ndutu, where “normally” they would have been, and yesterday our encounters with them after Olduvai to Lemuta suggested our intelligence was correct.

Mind you, there were wildebeest almost everywhere we looked or traveled in the southern quarter of the Serengeti/Ngorongoro. But the smaller scattered herds of maybe 200-400 were not a big enough or uniform enough group to be called “the migration.”

We headed to Naabi Hill, slipping and sliding as to be expected after yesterday’s incredible late afternoon downpour. On the way, we saw a family of three cheetah, a mother with two older cubs.

They were fat and sassy and not likely to hunt now, except that a juvenile Grant’s gazelle separated from its family group was trying to get back to it, and the cheetah were in the way!

I couldn’t believe how daring that young gazelle was, and it provoked one of the cheetah who gave it half chase. And that’s all it took for the gazelle to disappear into the sunset, apparently giving up whatever family ties prompted its initial reaction.

We saw another cheetah with full belly when we finally reached the Gol and then a lioness atop a kopjes, when we hit an empty but green plain filled with flies. That and confirmation of the droppings that lots of wilde had been there recently made us realize we were on the right track.

It was a lot further than I expected, given the intelligence we had, but the herds had obviously moved. Our intelligence was 3 days old and the herd was actually another 10k north and east of where I expected them to be.

But there it was, a “hot dog” shape of wildebeest perhaps 20-25 kilometers long and 3-4 kilometers wide. It lay north to south on the far eastern side of the Serengeti nearly touching Loliondo.

The northern-most portion was in the Barafu Kopjes, ridiculously far north for this time of the year. And the southern-most portion was … well, where we had stopped for lunch yesterday, at Lemuta.

We stopped for lunch on a high kopjes overlooking the veld. It was an incredible accomplishment finding this amazing spectacle, the greatest in the world, and everyone realized the long drive necessary to reach this point was worth it several times over.

The rest of the afternoon we spent cruising through the herds and making our way home. And towards the end of the day, we came upon the same four brother lions we had seen yesterday, and two of them were lying beside partially eaten ostrich!

I still have to think about this one. Lion don’t eat ostrich. Lion don’t defeather birds, and the ostrich feathers were in a pile. Lion don’t eat ostrich heads or bills, and those together with most of the necks of both ostrich were nowhere to be seen.

Seemed to me it had to be hyaena and our four brothers just got irritated with the fact the kill had come so close to them. Their bellies were still full from their kill several days ago. I’m sure they ate some of the bird, but most of it lay “unused.”

It was a fantastic, successful day!

We left the crater just after breakfast, and there was heavy mist on the rim as we drove around the northwest side past the down road which has been closed for reconstruction. The road then swings around to the west for about 4 kilometers of beautiful driving on the north side of the giant alter-crater.

Like so much of the veld today, it was lush and green, but I saw only a smattering of zebra and wildebeest. The road then rises briefly over the lip of the alter-crater before dropping onto the north side of the crater towards the Serengeti.

Whistling thorn acacia reappear, so therefore do giraffe! Lots of zebra suddenly, and as we descended, more and more giraffe. As we approached the road to Olduvai Gorge, large numbers of wilde and zebra mixed in with Thomson’s Gazelle covered the veld.

I hesitated thinking this was part of a large hunk of the migration, but sure was tempting to think so. Fortunately I said nothing and it ended before we actually drove into Olduvai Gorge.

After our fascinating tour of the visitors center and museum and special visit to the site where Mary Leakey found Australopithecus bosei, we continued off-road onto the grassland plains towards Shifting Sands.

We passed several Maasai herders, and I noticed they were now ranching sheep as well as goats. Saw lots more wild animals and right around shifting sands the wilde population seemed pretty dense.

We continued overland towards Loliondo, stopping at a kopjes near Lemuta for lunch. On that hour or so drive from Shifting Sand, we stopped several times to photograph kills covered with birds, golden jackal, and several baby wilde that couldn’t have been more than a couple days old judging from the length of their umbilical chord.

Lunch on a Lemuta Kopjes is always a highlight of the trip. The views are astounding, and the entire veld was peppered with animals. This was an important clue, by the way, that would help us tomorrow in locating the largest hunk of the migration.

But it was getting on, and we had a ways to go to Ndutu Lodge, one of my favorite. So we changed direction and began heading southwest to the lakes area of the Serengeti. Passed numerous eland that ran before we were within a mile of them!

Photographed lots of hyaena just waiting on the outskirts of water holes for some thirsty beast to drink. And we ran into four brother lion who had killed a day before perhaps, with giant bellies so large they could hardly walk.

We reached the main road and took a breather so people could photograph themselves under the “Welcome to the Serengeti” sign, and the drivers who had been working so tirelessly since early this morning could rest a little.

Then we started the last 25k to our lodge following Olduvai Gorge to Lake Ndutu. Halfway there it started to rain, and then thunder and lightning, then hail and then the rain became so heavy and the wind so dangerous we had to stop for a short time.

We literally couldn’t see because the sheaves of water falling from the sky were so severe.

I’ve lived through countless East African rainy seasons. I remember one of my camps blown away, of lodges and tented camps flooded. And perhaps it’s just the emotions of the moment, but it sure seems like the rain is harder, more and longer than in previous years.

We reached the Ndutu Forest just as the rain abated and got to our lodge around 7 p.m. It had been an 11-hour day, filled with tons of animals, extraordinary scenery and (lots of) rain. Until we had reached the main road to the Serengeti, about 40 minutes from our lodge, we hadn’t seen a single other vehicle other than our own four.

This is the Africa I love the best, and today reached all my expectations.

Cheetah jumping on cars went YouTube viral this holiday season, and traditional criticisms from wildlife managers was starkly absent. Is this OK?

Cheetah jumping on cars went YouTube viral this holiday season, and traditional criticisms from wildlife managers was starkly absent. Is this OK?

The newest video had nearly a quarter million hits this morning but it is hardly the only one. I stopped counting at 20 separate YouTubes of cheetah on cars, and there are countless stills on Flickr and even more individual photos on private blogs.

My own experience includes at least a dozen such incidents. Most of them were in Kenya’s Maasai Mara, but some of the most memorable incidents were in Tanzania’s Serengeti. The striking difference as relates tourism of the two areas – the Mara is generally very crowded and the Serengeti generally absent of crowds – has led me to believe that there is something hardwired in the cheetah’s brain that gives it a potential pet syndrome.

Hard-wired may be too strong, and I can understand how generations and generations of cheetah being unmolested by people could nurture up the same behavior, but either way, the cheetah is clearly the closest thing to a pet you’ll encounter on a big game safari.

Not every cheetah displays this friendly behavior. I’ve encountered many which are extremely skittish, although none of these frightened little beasts were in the Mara – they were all in the Serengeti or more distant places like Kenya’s northern frontier. The best I can remember virtually every cheetah in the Mara looked friendly.

Why do some, then, but not all jump on the cars?

It’s a pretty simple answer. A hungry cheetah begins its hunt in an incredibly laid-back fashion. The eyesight of the cat is so powerful that it can scan the plains with almost the same facility as a falcon surveying the turf below.

The best view is the higher one.

And like falcons and other raptors, prey is often discovered but then doesn’t always trigger an attack response. I suspect this is often because it’s just too far away, but there’s probably dozens of other reasons as well.

Perhaps the cat’s level of hunger just hasn’t reached the threshold of action, or perhaps the cat also sees competitors in the area and the cheetah is the smallest of the big cats, easily chased off its prey by a host of other animals like hyaena.

In any case, the cat on your car roof seems incredibly relaxed, hardly hunting. But that’s exactly what it’s doing. Fat cats – non hungry cheetahs – will never be found atop a car.

There is one exception. Youngsters learning to hunt will often play on the car, hungry or not.

There is one exception. Youngsters learning to hunt will often play on the car, hungry or not.

Not too many years ago, researchers and rangers were highly critical of these tourist interactions. Pamphlets were placed strategically on lodge reception counters and I even remember a series of “ranger talks” warning guests not to approach cheetah too closely.

The argument was that the cheetah was easily distracted by tourists, and would therefore often have its hunt disrupted. I found that specious.

But there are definitely reasons to avoid too close an interaction. Cheetah is the only cat whose claws don’t retract, so it has no power to decide whether to inflict a wound or just give you a love swipe if you accidentally surprise it.

I learned this when Kumati, an old cheetah that lived by Naabi Hill, jumped on my car as we were headed to the airstrip for a flight. No matter what we did, we couldn’t get him off. Finally I stepped out of the car and swiped him with my hat, which he ripped back in turn!

I learned this when Kumati, an old cheetah that lived by Naabi Hill, jumped on my car as we were headed to the airstrip for a flight. No matter what we did, we couldn’t get him off. Finally I stepped out of the car and swiped him with my hat, which he ripped back in turn!

Of my many memories of cheetah-on-car the funniest one was with two football players from a prominent American college traveling with their much smaller mother. We stopped in the middle of the Serengeti – virtually all alone for miles and miles – to watch a young family strolling along the plains.

Several of the youngsters jumped on the spare tire on the back of the vehicle. The right guard shoved his mother towards the front of the inside of the car, then ripped out one of my seats and pushed it towards the cheetah shouting, “Down Mother!”

A big male cheetah might reach 90 pounds. Most females are around 60 pounds, and this means they are generally about the same size as your lapdog.

Is there any real harm with all this?

I don’t think so. As I learned with Kumati, don’t try to pet them! But conceding a better view and just enjoying the experience strikes me as mutually beneficial!