A ranger’s report filed yesterday from northern Kenya explains so perfectly why lions in the wild may quickly becoming a thing of the past.

A ranger’s report filed yesterday from northern Kenya explains so perfectly why lions in the wild may quickly becoming a thing of the past.

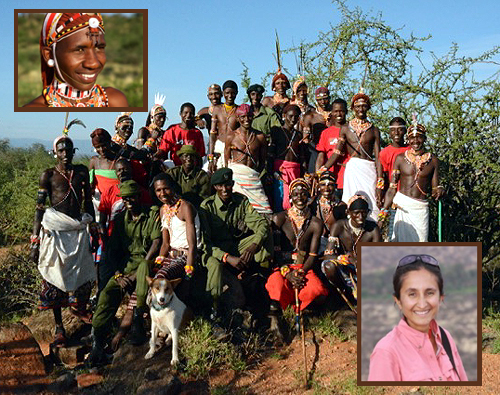

Ewaso Lions is a stellar NGO working in the Laikipia/Samburu region of northern Kenya, a beautiful semi-arid terrain just north of Mt. Kenya. The small under 25-person group is run by a 4th generation Kenyan Asian, Shivani Bhalla, whose list of prizes from conservation organizations takes up a dozen lines of her resume.

More than half the staff is composed of local mostly Samburu. Jeneria Lekilelei, the Field Operations and Community Manager, won last year’s Conservation and Field Hero Award from the Walt Disney Foundation.

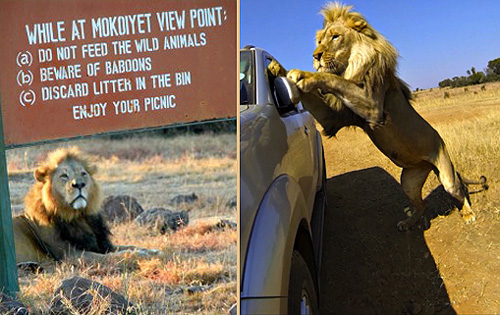

Jeneria’s field report explains that lion/human conflict in his region increases with the onset of the rains. During the dry season lions have a relatively easy time picking off wild game that must necessarily congregate at certain water sources.

With the rains wild game disperses. So does domestic stock: out of their bins where they’re fed hay during the dry season, they seek the same natural pastures that the wild game seeks.

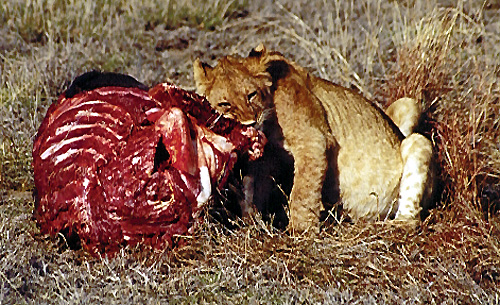

Jeneria recounts one morning when “the lions killed camels in 5 locations so I was getting calls from all over. I raced to one area where Lengwe and his pride killed a camel and its baby…

“Three warriors from the village came and they all had guns. I was sure Lengwe was going to be killed by these warriors, so I sat with them under a bush all day” and talked them out of the killing.

There are several critical back stories to this positive tale.

The first is pretty evident: “I was getting calls from all over.” These weren’t warrior’s whoops, they were cell phone calls. Even the most remote wildernesses on earth are peppered with cell towers and there are generally more mobile phones per person in the developing world than in America.

Cell phones represent increasing connections of everything, including government and people. Killing a lion in Kenya is a crime.

The second back story is of Lengwe the lion. Lengwe would be a goner in the truly wild world of times past. Jeneria first encountered Lengwe when he was nearly dead, incapacitated by a broken femur. Ewaso Lions mobilized a remarkable rescue operation that included not only rounding up vets and federal wildlife rangers to immobilize Lengwe, but even of transporting an X-ray machine into the area for a correct diagnosis.

Lengwe was not exactly nursed back to health, but he was certainly monitored carefully and eventually he became a pride leader. Losing Lengwe to three young warriors would have been a rather sorry end to an otherwise heroic tale.

Finally the third back story was the rationale that Jeneria used to dissuade the warriors from their revenge killing: Where were the kids?

Stock – whether camels or cows or goats – is traditionally the responsibility of young boy herders. As Jeneria recounts asking the warriors, “Have you ever heard of a camel being killed when herded by a proper person?”

The question shamed the warriors. The implied answer is also quite illustrative: lions won’t go anywhere near Samburu or Maasai herding stock and this particular stock was being neglected. Not tending stock doesn’t just remove protection, it essentially cedes ownership.

Because of the good work of Ewaso Lions, the great Northern Frontier’s predator is faring better than it would otherwise. Because of cell phones, Maasai boys herding stock are going to become increasingly delinquent so that they can pass their CPAs.

This wonderful story with wonderful, positive characters ended beautifully, but its lesson is proof things will not go well as currently arranged. Climate change and human progress might be at odds in some places, but in this case they are working hand-in-hand to wreck havoc on this traditional tapestry of life.