Like tigers, truly wild lions in Africa may becoming a thing of the past.

Like tigers, truly wild lions in Africa may becoming a thing of the past.

A prestigious group including Africa’s leading lion researcher, Craig Packer, claimed today in a report published with the National Academy of Sciences that lion populations will decline 50% in the next two decades.

I have already seen the decline in East Africa, most notably in Ngorongoro Crater. The report, by the way, claims that the adjacent Serengeti lion population remains healthy and is less likely to decline.

According to a summary by CBS News of the lengthy report, lions “are threatened by widespread habitat loss, depletions in available prey, preemptive killing to protect humans and their livestock along with poaching and poorly regulated sport hunting.”

The most serious decline will be in west and northern Africa, although as much as a third of the sub-Saharan lion population will decline. Sub-Saharan populations are healthier, according to the report, because of adequate protection in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

The very interesting detail in the report as to what exactly explains southern African countries’ better protections has much to do with fenced-in private reserves, a situation which today is about all that is left for Asian tigers.

Although most of these fenced-in, private reserves are not zoos as such since they are large enough with enough variety of prey game that the lions do not need to be fed, disease and/or injuries are often treated.

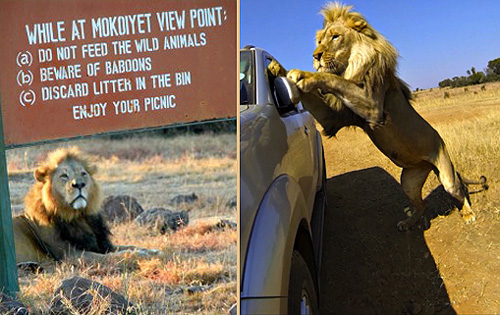

The lions in virtually all these cases become very habituated to people. Unwittingly, similar situations can occur in completely unfenced and unmanaged reserves like Nairobi National Park when visitor populations grow unusually large.

Fenced-in reserves and too many visitors change the cats’ behaviors. They begin to tolerate one another more than natural, adapting to a confined if imposed territory. Fewer larger prides, of the sort we see today in Ngorongoro Crater, replace more smaller prides with a net overall decline in numbers.

This usually makes them more dangerous, at least in the initial phases of this recalibration of behavior.

I’ve often written of a similar situation occurring in East Africa with elephants.

It was hardly a decade ago that I would tell clients traveling in the dry season that on a typical ten-day safari they could expect to see more than 125 lion. (A wet season prediction was around 80.)

In my most recent safaris those numbers declined by a third.

In addition to the crater I’ve noticed obvious declines throughout central Tanzania, southern Kenya and the Mara.

It’s likely that part of the “health” of the Serengeti is due to Mara lions moving out of the congested Mara. The Mara and its border of private reserves is also then itself bordered by intense agricultural lands and growing numbers of small towns.

Seeing a tiger in a reserve today in Asia, or a lion in a private, fenced-in reserve in South Africa is in my opinion massively different from those observed in truly wild situations.

The fenced-in lion is usually healthier but not as strong, fatter and not as lean, seemingly more disinterested in everything and more likely to allow approach, or even to approach the observer.

“Saving lions” will not be difficult. There are already too many lions in zoos and euthanization is now regularly used for older and infirmed animals when in years past these animals would have been nursed to health or kept alive for their genes and research potential.

And as with captive lions in zoos, fenced-in lions do extremely well, positively responding to a reduction in their territory when offered an adequate food supply.

So lions will be around for a very long time.

But not necessarily as I would like to remember them.