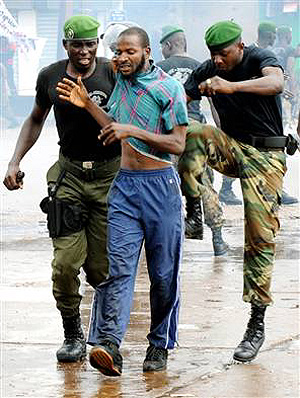

Americans are just as tribal as Africans. This week’s elections prove it. But while Americans may curse and protest, our visceral feelings don’t manifest into actual bloodshed. That’s the difference with much of Africa.

Americans are just as tribal as Africans. This week’s elections prove it. But while Americans may curse and protest, our visceral feelings don’t manifest into actual bloodshed. That’s the difference with much of Africa.

A good friend and 25-year old Africaphile who recently completed a stint with the Peace Corps in Guinea where ethnic violence is now erupting sent me the dispatch below. His heartfelt concerns built by nearly two years of working in an isolated village, learning the language and customs and making friends, now seem swept away by his inability to explain what’s happening, now.

Conor’s angst if anger is the same that drives ethnic violence. Those of us who have “fallen in love” (Conor’s words) with distant places and peoples come remarkably close to adopting aspects of that foreign society that attract us. We touch the same sphere of that complex culture as those who were born into it.

But we’re on the outside. We can sit on the sphere and enjoy something, then remove ourselves perhaps when something turns ugly. We both might feel the same thing. It’s just that we aren’t contained within the sphere like they are. We can release our grip and float away.

Conor puts it this way (excerpted from below):

I do not understand the fear of isolation in the same way, the fear or being shut out of the network that I owe my history and existence to. Therefore I do not understand the surge of belonging that electrifies every contact with those on the outside of the fence.

From my distant perspective, it’s the same awful panic that drives the old Delaware widow to elect someone who wants to privatize social security. Or the right-thinking Libertarian who stamps his foot on the head of someone who disagrees with him. These are puerile, unintellectual feelings. They lead to my loving Norwegian Methodist aunt hating her Jewish landlords.

Conor writes (excerpted from below):

I thought I understood ethnic identity….I thought I understood what the potential for violence smelled like, what it looked like in schools, and what it felt like when you walked through the market or hitch hiked a motorcycle ride to the next town…..

I obviously do not.

The main difference between Conor Godfrey and his Guinean friends is that he isn’t Guinean. He is not forced into the ultimate defense: attack the other, go on the offense.

Click here for a YouTube video of the current violence, then read the rest of Connor’s dispatch:

* * * * * * * * * *

Every day hundreds if not thousands of Fulani flee their homes in upper-Guinea for the safety of Fouta Jallon, the heartland of the Fulani people. They are both victims and victimizers of the neighboring Mandingo with whom they had lived peacefully for some time.

Guinea’s electoral crisis has resulted in a standoff between two remaining candidates representing these two largest ethnic groups in Guinea. Ethnic fault lines, previously well concealed beneath a web of inter-marriage, common faith, and necessary interaction, have reemerged into yawning chasms across which none save the artist or truly pious dare cross.

I left Guinea a year ago last week. As soon as my plane landed in the U.S. I began to mock the so-called experts who, I felt, read from outdated West African script as they warned of impending implosion in Guinea.

Did they know Modi M’Biliri Barry, my host father? Had they met Ousmane Diallo, my polyglot Peace Corps trainer who never had a bad word for anyone , or the Nene (mother) in Fataco that sold cassava dipped in hot pepper at recess in the courtyard, or seen Fulani and Mandingo students share benches in school, or chase the same girls on the beach in Conakry?

Because if they had—they would not, could not, suggest that Guinea shared anything more than a border with countries such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, whose blood soaked late 90s have come to define ethnic barbarism.

How many people like me have fallen in love with diverse, integrated peoples in far away corners of the world, only to look back with horror as dormant identities in those same friends surge from obscurity, thousands of times more potent than peace time associations?

After a U.S. friend with his Kenyan wife visited Rwanda’s genocide museum in 2006, they both expressed to me wonder at the intensity of feeling that could drive human beings to leave all empathy behind. But as violence then gripped Kenya a few months later that same woman’s facebook page was inciting violence in her home country from an ocean away, urging people to round up Luo and “do away with them.”

The educated Guinean ex-pats I now speak with in The States rarely seem any better. The same family that opened up their homes to their diverse neighbors last year is now a dues paying member of the their group’s most intolerant fringe, cum sudden majority, willing to believe all manner of nonsense about certain members of their community.

The exceptions are beautiful. Grand Imams in most major Guinean cities have issued stern and touching warnings against reprisals and generally appealed for peace and reason. Some of the most prominent musicians from all over West Africa recently got together to put this song together; it asks, in stirring and beautiful verse, and in all the right languages, for peace and unity in Guinea.

I also know that individual Guineans, of all groups, in Labe and in Kankan, in New York, Paris and Montreal, and all over West Africa, are praying for Peace….but my impression is that they are the exceptions that prove the rule.

The collective unconscious I belong to does not go nearly as deep, nor nearly as far back as the Mandingo or Fulani communities, but it should go deep enough to remember European’s genocide inducing arrival to the new world, or our subsequent enslavement of millions of souls, or the other countless atrocities that have been perpetrated in the name of constructed identities by people of every race, creed, and color…..yet I don’t.

I am watching, from afar, the subversion and transformation of Guinean society as if this has never happened elsewhere, somehow unfazed by the stunning regularity with which this process unfolds across time and geography.