There are too many elephants. So says, among others, the CEO of Elephants Without Borders, Mike Chase.

There are too many elephants. So says, among others, the CEO of Elephants Without Borders, Mike Chase.

“Too Many” is awfully subjective. But many countries share Kenya’s just published wildlife census confirming its population of elephants increased 12% in the last seven years, Zimbabwe has revealed plans to cull up to 50,000 elephants, and Botswana is “deporting” thousands of elephants back to their home country in Angola, as absurd as this sounds. (Do they have ID cards or passports?)

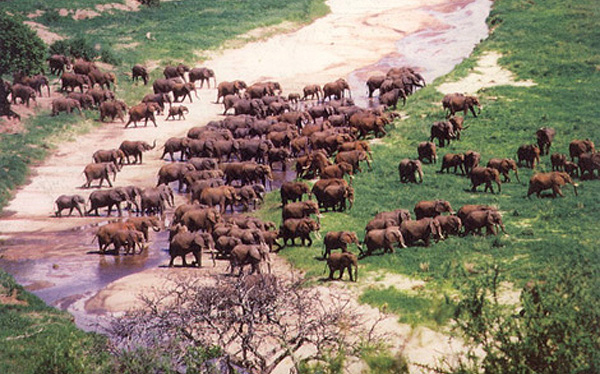

There are somewhere between 450- and 500,000 elephants in Africa, almost all in sub-Saharan Africa and three-quarters of them in only five countries: Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

This is probably about half what it was when I started guiding in Africa almost a half century ago. But consider this. The human population has more than doubled in that same time. Who should get the land?

The elephant population was actually very worrisome hardly three decades ago. The steep decline from poaching of the early 80s represented the peak of black-market ivory. It’s quite possible that the world population of elephants fell below 200,000.

That horrible trend line of the 80s and early 90s represented the abject stupidity of our species, concerned more with its immediate vanities than sustainability. Tens of thousands of wonderful individuals and countless excellent organizations responded by harassing world opinion, and global leaders were forced to create the CITES convention.

CITES was the turning point, not just in the decline of elephants but of many other species and as well, the great positive changes in the public’s perceptions of the wild.

I’ve written dozens of articles about CITES and its local law spin-offs, but several of my favorites were about a “dump roper” in Texas, another side-lining crook cowboy in Illinois and the end to selling Grandma’s necklaces on eBay!

All of these stories were of aggressive enforcement of local state laws essentially spun-off from CITES.

So the nosedive towards elephant extinction was stopped. The techniques were wildly successful and have probably contributed now today to the opposite problem: too many elephants.

By 2010 it was becoming apparent to me and many others that “poaching” was no longer such an evil enterprise as the criminal manifestations of local Africans with little or no hope for a decent future.

Instead of the giant corporate poaching of the 80s, with chartered helicopters and battalions of mysterious workers using bazookas and supersized nets, later poaching became a one-off affair of a group of disenfranchised and disenchanted young men.

One at a time the elephant tusks would find their way to some intriguing broker like the Queen of Ivory rather than dozens/hundreds of tusks packed into containers. Still the black-market was tenacious until China finally cracked down and forced its largest online retailers to remove all ivory products from sale.

At that point things turned quickly, and that was around 2016-2017. The trend line towards extinction was reversed long before, but the down line for annual populations clearly and unmistakably popped up.

And it’s been improving even more ever since, yet the “conversation about elephants” continued to be dominated by grandiose conservation organizations still panning the extinction theory! You can put practically every big conservation organization into this category.

This conservation pitch is woefully similar to the political “Big Lie.”

What was once a genuine plea to save our biggest land mammal has become the biggest conservation scam of the last hundred years. And guess what. It’s not helping elephants.

The Conversation. The conversation that we better start having is the natural competition between a growing population of humans and a growing population of elephants that is not sustainable without careful refereering.

“We need to take a holistic view of elephants and their long term effects on an entire system while considering changing landscapes, human beings living with elephants, anthropogenic changes to the land and the elephants themselves,” correctly states African Geographic.

And its pointless for Botswana and Angola to trade their excess back and forth, or for Zimbabwe to mass slaughter. What I think is needed is South Africa’s Kruger policies, which have changed over the last century always for the good of the overall ecosystem, including elephants. African Geographic’s excellent article linked to above details much of this successful strategy.

But it’s complex and sometimes necessitates a population decline. Sometimes, there’s culling. This is such an emotive issue that it’s hard to garner public support. It also becomes awfully divisive, pitting hunters against animal lovers.

Single issue politics is usually bad. Single issue conservation is, too.

When we migrate from “Save the Elephants” to “Save the Planet” we’ll discover quite quickly that elephants are an important part of that new mission and that the odds of saving both improve substantially.