Hardly had my business to show people big wild animals got off the ground when Peter Beard published his book, End of the Game. Now, I wonder, are there too many wild animals in Africa?

Hardly had my business to show people big wild animals got off the ground when Peter Beard published his book, End of the Game. Now, I wonder, are there too many wild animals in Africa?

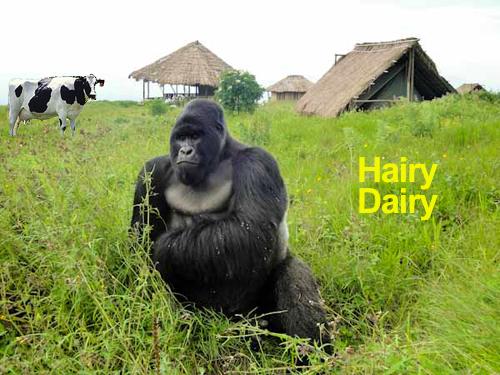

Yesterday we learned that the predictable “bamboo season” in Rwanda’s Parc de Volcan was bringing “as expected” many of the mountain gorillas out of their reserves into adjacent farmer fields. The battle between the cow and the gorilla, though, was not expected.

Researchers following the Urugamba silverback recorded him “charging a nearby cow” last week, although the expected bloody encounter was avoided when he unexpectedly stopped the chase. But cow-gorilla conflicts while troublesome are not what is principally bothering researchers.

Human-gorilla conflicts are escalating throughout the Virunga range, and give every indication that some biological threshold has been reached. The list is long but began horribly documented in 2007 when irate villagers stoned to death a gorilla that had entered their village.

An EWT client was one of the first ever tourists to visit habituated mountain gorillas back in 1979. Then, there were an estimated 280.

Today, the estimates range between 685 to more than 700, approaching a three-fold increase during my lifetime. Similar numbers apply to many animals throughout Africa, including other headliners like elephant and wildebeest.

Researchers are currently painting the human-gorilla conflict as not necessarily something the gorilla needs, but rather something it wants. This is the “bamboo season” as new shoots grow quickly with the onset of the seasonal rains. Gorillas “love” bamboo shoots.

In PdV many of the best and newest bamboo shoots appear first outside the park. The report of the incident between the gorilla and the cow was concluded by the researcher, “There are sure to be many incidents in the coming weeks surrounding the highly anticipated bamboo season. Stay tuned!”

In PdV many of the best and newest bamboo shoots appear first outside the park. The report of the incident between the gorilla and the cow was concluded by the researcher, “There are sure to be many incidents in the coming weeks surrounding the highly anticipated bamboo season. Stay tuned!”

Interestingly, this is exactly opposite to what the researchers in the PdV’s sister and adjoining park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Virunga National Park, claim. There, researchers wait anxiously for the “moment bamboo shoots are available” when their gorillas end raiding farmers’ crops and return inside the park boundaries.

So it sounds to me that there is no particular reason that new bamboo shots are outside rather than inside a park, and probably, in both parks they’re in both places. The human-gorilla conflict is more serious than where new bamboo shoots occur.

The human-gorilla conflict has been seriously documented ever since 2009 when an interagency working group HUGO was formed to deal with it. The name of the group was changed to human-wildlife conflict, in part because as researchers got into the problem they realized the area’s residents while concerned with gorilla conflicts were equally concerned with other burgeoning wildlife in the park, like buffalo.

A foot-high stone barrier is being erected around almost the entire PdV, and this seems to have helped stopped human-buffalo encounters. Near very productive farms alongside Sabyinyo volcano a trench has been cut, which seems to have impeded human-elephant encounters.

But a successful technique to discourage gorillas has not been found. Several years ago the International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP) encouraged using drums to scare away the gorillas, but one researcher in 2009 said, “I’m told they enjoy the sound and allegedly start dancing when the drums appear.”

And then this year the DRC gorillas became so familiar at tourist camps and area farms, that researchers began using drums again.

They still don’t dance. But it still doesn’t work.

One of the things that gnaws equally at my conscience and nostalgia is that the growing human-wildlife conflict in Africa is a reflection that years ago the precarious state so much big game found itself was, in fact, a natural if precarious balance with man.

But when man discovered he could make money showing animals to other men, which bought time to deliver a growing compassion as well as a separate understanding that biodiversity is essential to man’s long-term survival, big game became nurtured … developed.

And so, surprise, it prospered.

And so did man.

So the conflicts that existed so long ago that nearly made extinct such animals as the mountain gorilla are only more severe, today. The conflict resolutions are becoming more high tech, more intense and understandably, much more expensive.

And in some cases, such as with gorillas, there don’t seem to be any good conflict resolutions.

Ultimately this growing human-wildlife conflict in Africa will reach a breaking point, and if scientists are unable to stop the rate of growth of these animal populations by benign means before this happens, human policy that understandably favors humans will. And it may not be very pretty, then.