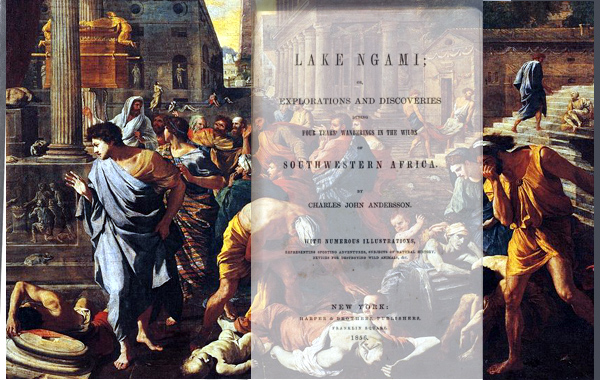

Shortly after crossing the parched deserts of what is now southern Namibia the explorer Charles John Andersson collapsed onto the embankment of the Hountop stream that ultimately led into the mighty Orange River. Dangerously relieved he almost fell asleep rather than drink some life-saving water. He had “made it through,” according to his book, Lake Ngami.

Shortly after crossing the parched deserts of what is now southern Namibia the explorer Charles John Andersson collapsed onto the embankment of the Hountop stream that ultimately led into the mighty Orange River. Dangerously relieved he almost fell asleep rather than drink some life-saving water. He had “made it through,” according to his book, Lake Ngami.

“But I was soon destined to experience a greater calamity… I was seized by a violent shivering fit which lasted three hours, then came the fever, of almost as long duration, accompanied by racking headache and profuse perspiration.”

These are classic symptoms of malaria. It was April just after the rains when malaria is most severe. But this was long before malaria was known and Andersson was convinced it was a pandemic.

The villages through which he passed had all been devastated by something, some “laid barren” by this disease. His own staff and guides were falling to it like flies. Even though he was several months walk from The Cape and several years from Sweden whence he came, he was convinced “the world was on the edge of death.”

Fear of pandemics was omnipresent among Europeans in the 19th Century. Medicine was advancing so rapidly that the scourges of the past were no longer considered God’s will or a wizard’s fury, but something scientific that ought to be – but wasn’t yet – mastered. “Mysterious scourges” now had names: smallpox, typhus, cholera, yellow and scarlet fevers.

“Up to this period my busy and roving life had left me but little time for serious reflection. Now, however, that the cares of the world no longer occupied my thoughts, I felt the full force of my lonely situation. During the long and sleepless nights I was often seized with an indescribable sensation of sadness and melancholy.”

Left without even rudimentary European medicine Andersson believed that the pandemic would kill him.

As we dare to believe we are emerging from our own pandemic I’m obsessed with Andersson’s frankness about his fears. Malaria is bad, yes, I’ve had it multiple times. There wasn’t an explorer in Africa that didn’t get it all the time. But it isn’t the devil’s work and if it doesn’t kill you in a couple weeks it’s easily forgotten.

Andersson had conquered the most brutal treks of any early explorer. He had carried infections in his feet and legs for months that would make a pig farm smell like a spa. He had lost most of the sight in his left eye to bacteria carried by flies and he had gone weeks eating nothing but “dinder weeds” that led to dysentery that really did nearly kill him and lasted months. This episode of “fever” lasted only a few days, but …

.. It must be a pandemic. The devil’s work. There was a reason that Andersson ascribed this relatively momentary sickness to something much greater, and he was incapable at first of admitting it. All he could do was journal the probability of death even though…

“Death itself I did not fear;” but removed from all those he loved “was an idea to which I could hardly reconcile myself. What hand would close my eyes? what mourner would follow my coffin? or what friend would shed a tear on my lonely and distant grave?

“I was alone! Oh, may the reader never experience the full meaning of that melancholy word!”

Andersson recovered far more quickly than from his countless other ailments. And once fully lucid he was still certain the devil’s pandemic had tried to get him, and that his recovery was miraculous. He felt uncontrollable euphoria that he was alive, and everything around him seemed to validate the miracle.

Between 7 and 8 o’clock every night “when reading by the side of my bivouac fire, I was suddenly startled by the whole atmosphere becoming brilliantly, nay, almost painfully illuminated. On turning to the quarter of the heavens whence this radiance proceeded, I discovered a most magnificent shooting star, passing slowly in an oblique direction through space, with an immense tail attached to it and emitting sparks of dazzling light.”

Then in the glow of Secchi’s Comet Andersson wrote something I would never have expected, something you can search endlessly in vain for through all the old journals of early explorers.

He conceded his epiphany and the reason he was so certain that his illness had been part of a pandemic. He referred to those he normally called “primitives”, “Hottentots”, “natives” and so forth … as “people.” This is a thunderbolt those of you who don’t waste your time reading old African books might miss:

The “pandemic spread like wildlife throughout the length and breadth of Great Namaqua-land, and vast numbers of people succumbed under it.”

There were few other places in Africa at that time with the exception of the great Sahara that were as sparsely populated as the Great Namib, but Andersson was never alone. His own crew at times exceeded 200 workers. Some of Stanley’s expeditions approached 700. Apart from three or four dim-witted children of the first missionaries these entire staffs were composed of indigenous peoples. In Andersson’s case, Damara or Namaqua locals, and he treated them with utter disinterest and superiority because in his mind they were not human.

Perhaps I’m being too hopeful that Andersson had a moment that broke down this racist and myopic view of civilization gleaned from just a single word of his voluminous works.

But the presumption leads to our own corollary.

Many of you couldn’t hug an aged relative barred inside a sealed home. Many were forbidden from even saying goodbye except through Facebook to a loved one dying. Most of us missed innumerable friends and family and holiday celebrations and masked our identities wherever we went. Chances are almost all of you reading this succumbed to the “full meaning” of Andersson’s “feeling alone.”

Andersson’s brush with the devil, his discovery of “utter loneliness” led to an epiphany that there was no difference between himself and the Damara. With all his education and money and properness he conceded that he was no less likely to live or die than the primitives.

It wasn’t a nursing room or hospital barrier or lockdown regulations that divided Andersson from the mass of people around him. It was his conception that wiped the indigenous person off the landscape like an eraser over a white board. This is a lot harder to overcome than opposing voting rights.

What’s your epiphany?