Kruger National Park in South Africa remains the best managed large wilderness on earth. (Yellowstone is close but suffers from too little regulation because consumer demand is so high and ranchers so powerful.) But “best managed” does not mean most “spectacular” or “awe-inspiring” and definitely not “wildest.” Those attributes belong absolutely to the Serengeti.

Kruger National Park in South Africa remains the best managed large wilderness on earth. (Yellowstone is close but suffers from too little regulation because consumer demand is so high and ranchers so powerful.) But “best managed” does not mean most “spectacular” or “awe-inspiring” and definitely not “wildest.” Those attributes belong absolutely to the Serengeti.

And it’s the reason the Serengeti is so much more threatened than Kruger. The wildness of the Serengeti just doesn’t fit in with modern life.

Poorly managed and under-resourced kids are still being trampled by elephants, farmers are victimized by diseases like hoof-and-mouth and yellow fever that run rampant in a truly wild environment, and necessary dams and structured catchments essential for agriculture can’t be implemented without random destruction to the wild.

So for the time being the Tanzanian citizen is being sidelined so long as foreigners like me pay so much to experience the untampered and pristine. That takes little management, just the sacrifice of all those who live nearby.

Unmanaged wildness like the Serengeti isn’t just an extant biomass tinkered to death in places like Kruger, but a fragility of the extremes. It’s wildness perforce. And it can’t last. In the long term the only hope for the Serengeti is that it be transformed into a Kruger. That will be so expensive.

But Kruger will outlive the Serengeti if the Serengeti fails in its transformation. Kruger will then accede to the “wildest” left.

You can imagine the pressure that modern society has on wildness, particularly as that wildness is large and deadly whether that be in the form of a 6-ton charging elephant or snap of a puff adder.

But the elephant and the adder won’t survive without tens of thousands of other creatures and plants. The richer the biomass, the more complex and usually larger is the biosphere or area that contains it.

Kruger managers and scientists over the years have just exceeded every other earthly attempt to preserve the richest possible biomass in the smallest possible biosphere – and it isn’t small by the way. When including the very large buffer private reserves that surround Kruger the area pushes 9,000 sq. miles. Roughly the size of New Jersey, New Hampshire or Vermont.

Active culling, weeding, well drilling and damming are all tools of Kruger scientists and managers, and using near supercomputers to predict “carrying capacity” they are able to anticipate all the menaces of climate change.

Kruger managers deal with this grand wilderness the way master gardeners at Kew move around blades of grass or NASA scientists tinker with microthrusts on Hubbles hundreds of jets.

In the context of the unimaginable pressures of modern society, it works. It might not preserve my Serengeti, but it will be the next best option.

South Africa’s Daily Maverick is running an excellent series on the history and future of Kruger. Click on the preceding link to read it in full or listen to the audio version.

The author is appropriately not a scientist or manager but a self-taught explorer, Don Pinnock. Released from vocational prerequisites or being boxed in by excessive science Pinnock is able to convey an overview which I think is fabulous.

Pinnock is well positioned to take on hunters, politicians and scientists combined as he dabbled in them all. Like my own difficult coming-to-grips with the forced relocation of Maasai from the Serengeti, Pinnock recounts unabashedly the forced removal of nonwhites from what would become greater Kruger.

Without those immoral removals, the wilderness of both places would have been compromised. The raw science we’ve been able to extract from them up to today would have been severely limited had those immoral actions not been taken. It makes the whole process devilishly wrong if we can’t use those benefits now for the betterment of all mankind. Climate change, ruthless politics, pandemics … justification seems problematic.

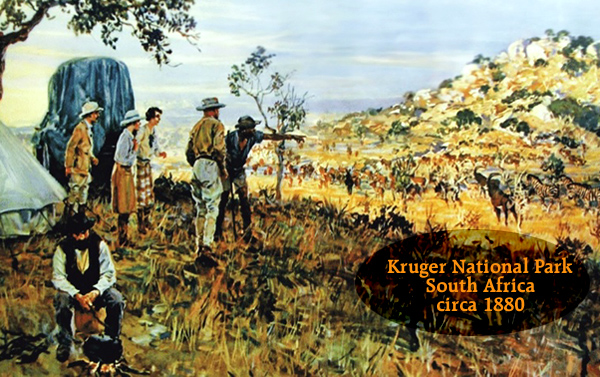

But there’s a lot more than gloom and doom in Pinnock’s chronology of the park. He has some absolutely great early photos.

And I love some of the anecdotes Pinnock provides: Kruger is named after the boorish Boer and gruesomely rigid President of the Transvaal, Paul Kruger. President Kruger remains a folk hero of the right, the cowboy who defeated a British army.

But as Pinnock puts it, “The name [Kruger] was purely political. The Volksraad minutes clearly show that President Kruger had never…in his life thought of wild animals except as biltong.”

The series is short but clearly is material for something much longer. Hope it happens!