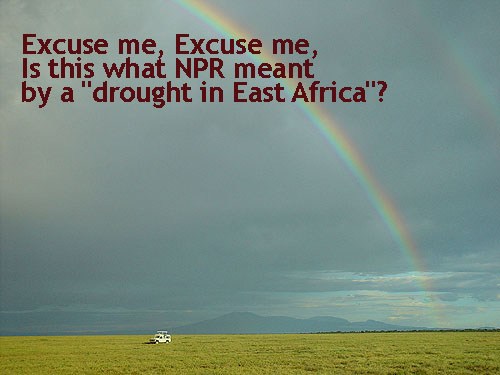

It’s raining in the Mara; it should be: That’s not news. It’s not raining in northern Kenya; it shouldn’t be: That’s news. Go figure.

It’s raining in the Mara; it should be: That’s not news. It’s not raining in northern Kenya; it shouldn’t be: That’s news. Go figure.

In between truly cataclysmic reports of America’s political constipation last week, many news sources were reporting on the “calamitous” drought in “East Africa.” One concerned consumer emailed me:

“My husband and I are scheduled to go on safari to [East Africa] in 3 weeks and are very concerned since hearing stories of devastation and the death of wildlife due to the drought. We are insured for the trip. Do you recommend we cancel and visit another time when conditions are improved? We have spent an awful lot of money and don’t want to spend 2 weeks in a dustbowl viewing dead and dying animals.”

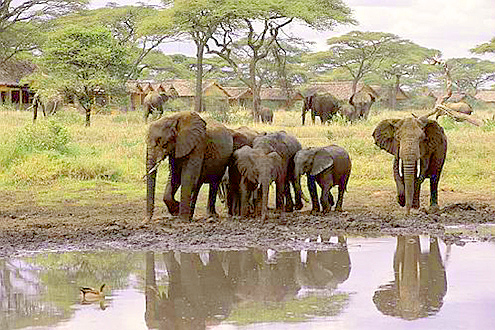

My office explained it was raining in the Mara. The excellent Governor’s Camp there reported 85.5 mm of rain in June (3.37 inches), a little less than normal, but nothing to write home about.

There are three important issues here.

First, “East Africa” is a big place. When you include all of Somalia, as NPR did in its weekend reporting, the area is nearly the size of half the continental U.S.

There’s a drought in America. There are devastating tornadoes in America. Floods are killing people in America. Wild fires are forcing people out of their homes in America.

Dare you visit the Blues Festival in Brattleboro, Vermont?

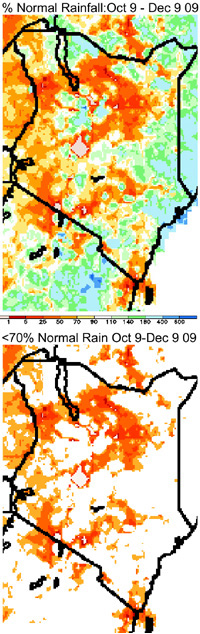

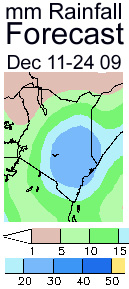

Columbia University’s excellent climate reporting website shows the actual precipitation over the last twelve months. (To get the “loop” actually looping, you may have to click on “Precip Loop” in the left-hand blue panel.)

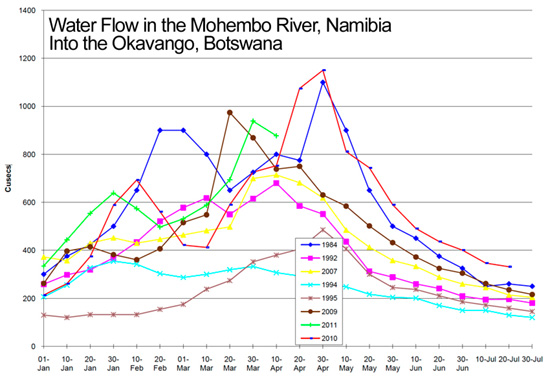

When corroborated with many other similar data sources, what we know is that overall “East Africa” has a pretty normal rain pattern for this year. Somalia and northern Kenya less than “normal” and much of the prime game viewing areas of Kenya and Tanzania normal or just slightly below.

That’s the first issue’s facts. I know in today in America facts seems to matter less and less, but I can’t seem to drop the habit of referring to them.

Second. Climate change is deeply effecting all the tropical regions of the world, including East Africa, more quickly and more extremely than in much of the world including America. This is because of the highly complex way that weather works at the equator. Even when you look up from the equator at the sky, clouds rarely move at all, the confluence of multiple jet streams and mixed up “corioloses” is one of the most complicated swirling and twirling air patterns on earth.

In a nutshell the result has been to make dry drier, and wet wetter. It’s the reason we do have “drought conditions” in northern Kenya almost constantly, interrupted by a season of devastating floods.

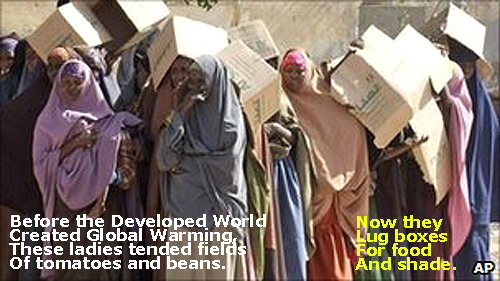

Three. And probably most important. The human catastrophe occurring in Somalia, northern Kenya and Ethiopia is hardly new. And the fact that it’s being reported as news is a sorry indication that we don’t care as much as we should.

Do you remember “Live Aid”? That was nearly 30 years ago. Things haven’t changed much since. Admittedly, dry is drier, and there are more people to feed, so famine is more likely and will now occur more often.

Do you remember “Blackhawk Down”? That was nearly 20 years ago. That’s when Bill Clinton let Somalia implode. It’s never come back together.

The human catastrophe in a part of East Africa is human made, not weather made. True, the desert has been growing literally for millennia from north to south on the continent, and East Africa is near the dividing line moving south. But desertification in Africa is not news, happens at a relatively slow pace and can be adequately dealt with by proper human development.

And fresh, good, potable water has been a growing catastrophe in Africa for decades. This, too, has been known for 20-30 years and there are ways to deal with it.

It is the politics of fear, egocentrism, greed and lack of compassion that has been growing at too fast a pace.

It’s raining in the Mara. You can proceed nicely on your safari.