Safari travel beginning at the turn of the century has been increasingly defined by luxury. It’s a trend that’s been fabulously successful for investors and consumers alike.

Safari travel beginning at the turn of the century has been increasingly defined by luxury. It’s a trend that’s been fabulously successful for investors and consumers alike.

Broadly speaking there are three types of places to stay in East Africa when on safari: Tuesday I wrote about the “flash-in-the-pan;” yesterday of the thoroughly reliable and unspectacular [“Thruns”] and Monday I’ll predict for both investors and consumers the future opportunities for all three types.

As any tourism market matures and grows more competitive, “luxury” is added to “price” as a sales point. It starts first with existing middle-market properties that are similarly priced as a reason to choose between them.

But with time “luxury” becomes a sales point all to itself, quite apart from price, and with exotic markets like East Africa in particular, it just seems a natural component of a destination that is expensive to begin with.

Everything modern in emerging countries (except mobile phones, it seems) is expensive: Cars are more expensive, modern homes are more expensive, modern clothes and so forth. And so is travel.

This is because all those things depend on imports: Fuel, building supplies and parts, many foodstuffs … and often, even staff, must come from abroad.

As this expense grows with time and relative to similarly distant destinations whose economies are maturing faster and therefore producing those necessary items locally (like China), it becomes more difficult to justify the higher costs.

Unless, of course, someone spreads rose petals up to your steaming four-claw Victoria bathtub which is placed beneath a giant chandelier and in front of an 12-foot window that overlooks Ngorongoro Crater.

And then the race to see who can make the most luxurious property is on. And the winners corner that extremely valuable part of the traveler market, the one that is pretty immune to even the near cataclysmic ups and downs of a global recession: the market of the rich.

This is what I call the moment’s splendor [“Moso”] type of East African property, and I choose that descriptor advisedly. Once outside of your four-claw bathtub back on the road, you won’t be able to avoid the innumerable bumps, horrible dust and lack of air-conditioning.

You won’t be able to easily replace your shampoo if you spill it, and the national grid might be down so no matter how good the wifi is in the room, there might be no internet. Plenty of hot water, when there’s water at all if the urban property dares to rely on mainline supplies.

The luxury is very confined to where you eat and sleep at night, and when something goes wrong, like no lights, you suddenly notice the wilderness more than you ever expected to.

And even when everything is going according to scheme (which I’m happy to admit is more and more with every passing day), and you are taking pictures of that magnificent lion pride out on the veld, you as the luxury traveler feels and experiences nothing more than the pensioner staying at a modern hostel who is in that old minibus on the other side of the lion pride.

The splendor can be quite limited.

But it seems to have worked. There have been few “flash-in-the-pans” and virtually no Thrun properties built in East Africa for more than a decade, but there is a plethora of new, luxury places to stay.

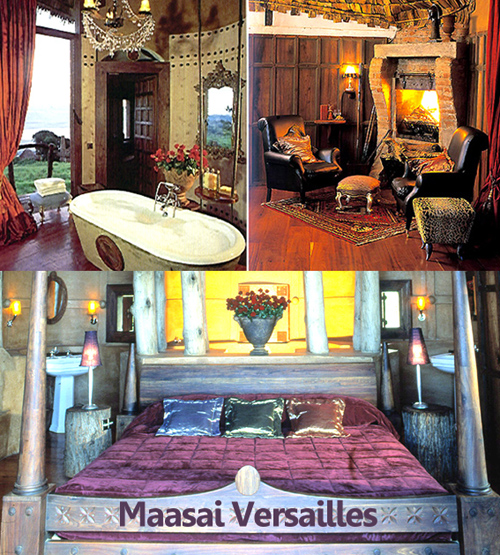

The most famous one in East Africa is Ngorongoro Crater Lodge, which we call “Maasai Versailles.” I’ve often stayed there and often written about it, positively in the beginning and negatively with time.

With time you begin to realize how “momentary” the moment is in the context of a good safari, and then the costs start to seem outrageous.

Prices at Crater Lodge vary between $1000 and $1650 per person per day, and when bundled with the other costs associated with a safari (fees, transport, etc.) this can be up to 10 times the cost of staying at a “thoroughly reliable and unspectacular” property, like the Serena Lodge about ten minutes down the road from it.

But it takes time and multiple visits to realize how “momentary” the moment is, and there is little question that the good luxury properties in East Africa do their trick. At least part of it. Reviews are pretty solid and good. What remains to be seen is if they – like the Thrun travelers – return multiple times.

We don’t have statistics for this, but my sense is that they don’t. Thrun travelers are among the most repetitive travelers in the world, returning 3-4 times during their lifetime of travel.

I don’t think that’s the case with Moso travelers, and that’s the part of the trick that might be missing with them. (More about this on Monday.)

Crater Lodge is hardly my favorite in this category. My favorites include Gibb’s Farm (which straddles this category with the Thruns), Dunia Camp (Serengeti, as well as many of its sister camps in the Asilia chain), Sarara (northern Kenya), Sand Rivers (The Selous), and Swala (in Tarangire).

Today, travelers accustomed to luxury won’t give it up just to have an exciting safari. Indeed, they did in the 1970s and 1980s. But times have changed, services have improved: There are no more 19th century aristocrats who dress for catered dinners in Kensington but use ferns as toilet paper while hunting lions. Today, there is a choice, however flawed it can be, for a “luxury safari.”

That’s the Moso mantra, and it’s what drives both investment and use of luxury safari properties in East Africa. But will it last?

See my next blog, Monday.