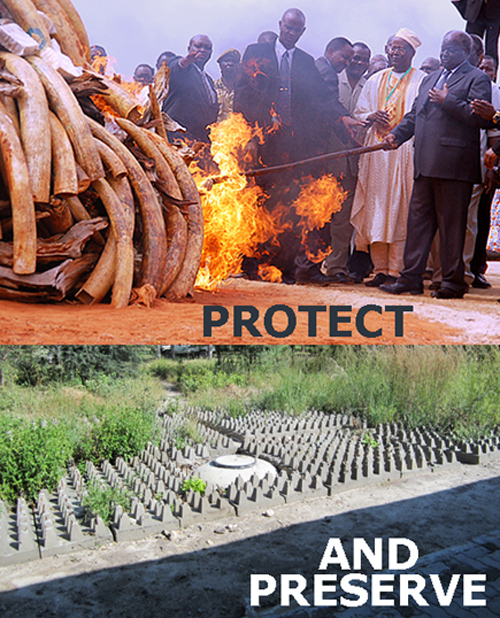

Protecting wildlife in Africa is a contentious issue, but Wednesday the Kenyan government publicly and forcibly illustrated its commitment to do so. There was no equivocation left in the pile of burned elephant tusks in Tsavo National Park.

Protecting wildlife in Africa is a contentious issue, but Wednesday the Kenyan government publicly and forcibly illustrated its commitment to do so. There was no equivocation left in the pile of burned elephant tusks in Tsavo National Park.

It wasn’t just that 5 tonnes of confiscated ivory, worth close to $1 million on the black market, was being burned to ash. It was be being burned to ash by the President of Kenya, Mwai Kibaki.

And standing next to Kibaki were Kenya’s minister for Forestry and Wildlife and Minister for the Environment, as well as Uganda’s Minister for Tourism.

Kenya fought tooth and nail earlier this year at the CITES convention in DOHA to prevent elephant protection from being downlisted internationally. It fought hard against a formidable coalition of southern African countries, spearheaded this time by cousin, Tanzania. Kenya won.

The arguments Kenya had to successfully counter to defeat the initiative more or less all wrapped up into one: enormous revenue can be generated from the sale of ivory. In its most angelic form, this comes strictly from ivory sales by governments to governments of culled or naturally dead elephant, and in its slightly less acceptable form, from the sales of ivory confiscated from criminals.

But Kenya prevailed. Tanzania and its southern African countries are still grumbling.

Public support to loosen the restrictions on elephant protection, however, has numerous explanations. First and foremost is the scientific battle whether there are too many elephants right now. It’s similar to thousands of American communities that consider deer culling.

Many American communities that cull deer champion their subsequent efforts to give the meat to soup kitchens following one sniper’s moderate aim. But what do you do with 15,000 pounds of inedible meat after you;ve had to hire a military battalion to kill a single monster? And then, what do you do with the ivory, whose value is indisputably remarkable?

The next set of arguments is more compelling to the public that lives near elephant who almost universally believe one elephant is too many: Farmers lose tremendous amounts of crops annually to elephant raids, towns and villages suffer building attacks and road destruction, and federal outlays to protect elephants and their sanctuaries are becoming increasingly expensive.

But apparently not so expensive as to challenge the balance of tourist revenues. It’s the economy, stupid. We all applaud President Kibaki and his government for this dramatic show of public support, but … we all know why.

Pull the plug on tourist revenue is to pull the elephant gun trigger. Imagine if a fifth to a quarter of your local town’s property taxes came from foreign tourists paying to see deer or racoons. There’d be a whole different way of looking at planting roses.

I’m uncomfortable with this fact, just as I’m uncomfortable with current American politics driven by the almighty dollar. But … it’s the economy, stupid. Yet by pushing this moral and ethical if even scientific argument down the road, it pushes an ultimate understanding of it to the edge of the cliff.

Leakey may be exactly right that we are in the 6th great die-off, and that species decline is way behind our ability to control. But we know that species decline is fundamentally bad. And we know that no species declines all by itself, it drags much of its ecosystem and related species right down the drain with it. So governing this moral if academic argument by current economics is childish, way too short sighted.

And even more pressing is constructing the right now balance between the stresses of protecting the species and the negative human ramifications of doing so.

We need to right now figure out ways to protect farmers who live near game parks. Southern Africa does a better job of this than East Africa.

See the concrete and steel elephant grating of the “AND PRESERVE” picture above that I took earlier this year in a Botswana park. It’s so simple that it effectively keeps elephants away from the showers and toilets of a public camp site within the park.

But it’s terribly expensive, and East Africa claims not to be able to afford such measures. Instead, ruefully inadequate trenches and fences and electric wiring are still used. It’s a miserable control. It does little but further aggravate the farmers.

And if the farmers and school teachers are aggravated, today, what happens in the next decade when tourism revenues sink below agricultural production, or social services properly created by better education?

You guessed it. The elephant gun trigger gets pulled.