We had finished a fabulous afternoon game drive heading back to camp when an incredibly wild family of elephant intersected the road. I hesitated not knowing if we should proceed.

We had finished a fabulous afternoon game drive heading back to camp when an incredibly wild family of elephant intersected the road. I hesitated not knowing if we should proceed.

Most of the elephant found in Africa, today, are relatively docile: they’ve been habituated to tourists for generations.

This is not true, though, in the more remote parts of Africa or even in the remote parts of its protected areas. That’s where we were: the southern half of Tarangire National Park.

According to the great elephant researcher, Charles Foley, about 2800 elephant live in the northern part of the park, and he calls them “sedentary.” An uncountable number – because they change so often – live in the southern part where we were staying and are “transitory.”

The transitory elephant are much wilder, and I think, healthier. They come through the southern half of Tarangire not to start a home, but to get somewhere else: like the eastern savannah which is equally remote.

I can usually tell the difference after just a few minutes of looking at a family. The sedentary elephant have lost many traditional behaviors, such as keeping their distance from other families and flapping their ears by rocking back and forth their head in warning.

This is because, in my opinion, there are too many elephant in this area. They’ve adapted “socially” by changing their customs. So today in the northern part of Tarangire and many other very insular protected national parks in Africa you can easily see 200 or more elephant together, males, young and mixed families.

They no longer shun other families, because — well, there just isn’t enough space to do so.

Not with the transitory elephant of Tarangire! So just as we had finished the afternoon game drive and were trying to get back to camp before dark, this one large, healthy family of 15 blocked us on the road only 40 meters in front of us. We’d watched them come down, heading for the swamp to water, and taking angry note of two other smaller elephant families in the vicinity.

The grand matriarch started some serious vocalization. This doesn’t mean just trumpeting, but deep rumbles of which we can hear only 10%. The remaining 90% are below our decibel level, so if we can hear rumblings, we know a lot more is being said!

We stopped in the road as she pulled her ears out and moved her head back, a precharge signal. So – but for only a moment – did the other two elephant families stop and take note of this swaggering grandma, but then the matriarch of the nearest one seemed to dismiss the challenge, turned her head to go and continued to saunter away.

The grand matriarch of the wild family lowered her head, trumpeted and charged the insubordinate matriarch of the family walking away.

The matriarch of the retreating family turned and faced her challenger for all of a second. By then the massive likely near 4-ton wild matriarch was practically upon the sedentary matriarch, who then began to run away from here.

But it was too late. She poked the retreating matriarch with her tusks eliciting a trumpet of pain as that smaller family fled faster and faster away. The grand matriarch then huffed and puffed a couple times before slowly walking back to her family, which had gone dead still.

I had decided we couldn’t move while she was running, because her stride together with her speed produces a 4½ ton projectile we couldn’t possibly outrun.

So began the standoff with us. The rest of her family were as still as possums as she jogged back to their front and faced us square on. The rest of the family as if on queue began moving again, seemingly in no discernible direction, just sort of milling about but suddenly we were surrounded.

Any one of the larger adults could have flipped us over. I have a front roof latch above the driver’s seat in the Landcruiser. It was open and I was standing straight through it, the first human she could sense. My clients were all standing up from the back seats.

My group was amazing. I know everyone’s hearts were beating frantically, including my own, but everyone was dead silent and unmoving.

The matriarch waved back and forth in front of us, her giant ears flopping in rhythm, but the good sign was that there was no vocalization.

Most elephant lose much of their sight after about ten years, but they continue to develop an acute hearing and smell. A brush of my bird book against the open roof, someone who is chewing gum and opens their mouth – these are the kinds of things that a grand matriarch standing only 20 meters away might take offense at.

So we just waited. Finally, she settled down and led her family down to the water away from us.

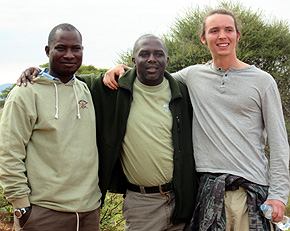

Mary Disse, who is usually not, was speechless! Everyone got extraordinary pictures, but more importantly, experienced viscerally the excitement of truly wild Africa.

We had a grand two days in Tarangire, Africa’s best elephant park. In addition to the tembos, we saw leopard, cheetah, lion, hundreds of impala, buffalo and wildebeest; thousands of zebra, dozens of bird species, and were incredibly lucky to have also encountered oryx and kudu. It was an extraordinary success.

Now we’re relaxing at another of my favorite places, Gibb’s Farm, before heading to the crater. Stay tuned!