Yesterday I saw more endangered big game species in four hours than I usually see in a decade of safaris in Africa. Add to that a manipulated zebra species but frankly, I’m going to have to work on having enjoyed this.

Yesterday I saw more endangered big game species in four hours than I usually see in a decade of safaris in Africa. Add to that a manipulated zebra species but frankly, I’m going to have to work on having enjoyed this.

Mokala National Park is South Africa’s newest national park. It’s a massive big game wilderness laboratory. Fifteen years ago there was nothing here. Today it contains the largest concentration of near extinct big game on earth.

The small park is 75 square miles about an hour south of Kimberley. The terrain is eerily similar to the flatlands of Laikipia, Kenya: smaller acacia trees sparsely dotting massive grassland plains.

The climate, however, is harsher than Laikipia, freezing in the winter and suffocatingly hot in the summer. This is where South Africa’s great Karoo (desert) meets its fertile midveld. It’s one of big game hunters favorite places, and on our drive down from Kimberley we passed one game farm after another.

The current impressive population of big game represents the original and second generations of animals translocated here from other parts of the country, particularly from an old national park, Vaalbos, that was closed under mysterious circumstances about 20 years ago.

Vaalbos was a natural wilderness and like Mokala perfectly located on the boundary between two unique climate systems, the desert and the fertile agricultural lands of the midveld. That provides a rich ecosystem that can sustain many different big game species.

Like most of South Africa’s parks the reserve is entirely fenced, but in this case double-fenced at several entry points. This is because the game being grown in the park is among the rarest in the world.

The animals are unusually tame. There are no predators and no plans to introduce them. The largest carnivore is the rather benign brown hyaena, which in its best situations is rare, elusive, very nocturnal and solitary.

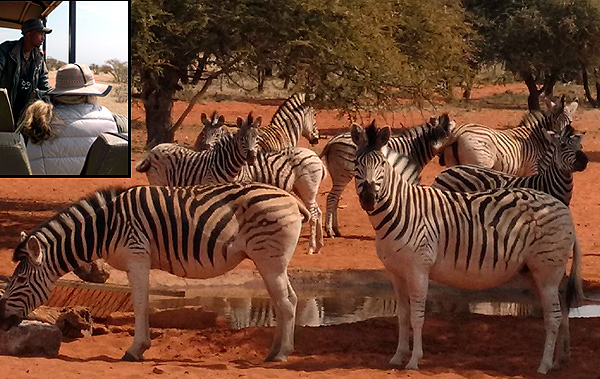

Nor are there any elephants. While the game here isn’t fed, it is watered with a number of large bore holes and we watched zebra enjoying the salt licks placed beside the water holes. But the game management is intense, and elephants are the single greatest disrupter of any ecosystem.

Mokala’s intense game management disturbs me. Common animals that were likely in the park prior to its creation, including impala and warthog, may soon be moved out or culled. Our ranger guide said they are considered too competitive with the endangered game being nurtured for the natural food sources available.

The “Quagga” is the “Prester John” of wildlife. For years South Africans claimed ownership of this rare zebra species found on remote parts of the country’s grasslands. Anyone seeing one recognized the differences: much whiter with much of the animal having no stripes and stripes converging into curly cues, and often large yellow washes on the hinds.

As soon as DNA typing was available the quagga was debunked. It’s not a separate species and the current ongoing argument is whether it’s even a sub-species, something that DNA typing has a harder time discerning.

What I and most conservationists believe is that it’s simply an interbred zebra. All interbred creatures display unusual characteristics. South Africans, park authorities and private ranchers alike have been selectively breeding zebra for more than a hundred years. I think they simply got caught up in their own enthusiasm.

Yet Mokala decided a few years ago to selectively breed its relocated zebra with the expressed intention of recreating a pure quagga, despite the definitive science that interbreeding is destructive. We saw at a water hole the result.

Fortunately, the program was abandoned. Yet park authorities remain infatuated with the “blue” and “black” wildebeest they claim to separately have, and the many black springbok and one black impala that we saw.

Melanistic animals are common. Consider your black squirrel and the many black varieties of birds. There’s nothing uncommon or unusual about this, but an attempt to selectively collect them is problematic as a conservation objective.

Bottom line is that there is no other place in the world with so many free-ranging rare species of big game, and the South Africans should be commended for putting so many resources into preserving these precious animals.

But the wild it was not. For that we now go to Botswana.