Death, destruction, despair and poverty … all for an attractive price! For less than $30 per person you can be guided into Kenya’s most famous slum! Kibera Tours dot com. “Experience a part of Kenya unseen by most tourists: KIBERA The friendliest slum in the world!”

Death, destruction, despair and poverty … all for an attractive price! For less than $30 per person you can be guided into Kenya’s most famous slum! Kibera Tours dot com. “Experience a part of Kenya unseen by most tourists: KIBERA The friendliest slum in the world!”

The half-day sightseeing trip in Nairobi promises to visit an orphanage and school, a bead factor and a typical Kibera house before the piece de resistance: the biogas center: “a fantastic view over Kibera and picture-point. You can see that also human waste is not wasted here.”

This is disgusting. Tourism at its worst and most exploitive, revealing the basest inclinations of ourselves and reenforcing ridiculous notions that poverty doesn’t exist at home.

Kibera is the largest of Nairobi’s 7 or 8 slums, which slip around the city in endless tin and fumes. Not even the Kenyan government census can estimate the size, but the best guesses I’ve seen put the slums at several million people compared to the residents in the city at around 3½ million. The slums are a dissimulating fraction of greater Nairobi and would be an incessant inferno in the developed world.

But in Africa they maintain an unusual tranquility. To be sure crime is endemic (see the film, Nairobi Half Life) and ethnic feuds that plague Kenya from top to bottom can produce particularly vicious moments here, but unlike slums in the developed world there is no boiling cauldron of the poor ready to murder the rich.

Nairobi slums are often stepping stones from poverty, completely unlike the imprisonment of slums in the developed world. Emigrants from impoverished rural areas without proper education or training live for a few years in the slums and develop the minimal skills needed to work in the modern world.

Then they move up and out. Not yet has Kibera fashioned a whole class of people forever imprisoned like the old Harlem or Cabrini Green in the U.S., or the Cape Verde barreos of Lisbon. Kibera will indeed become another Cabrini Green if something isn’t done this generation. But for the moment, the slums are relatively too young to have become a blighted institution.

Nevertheless, they look the same. And the nuance I argue above is not something that can be seen on a short visit. But slum tourists don’t come looking for hope.

What do they come looking for? Why does a tourist pay to come here?

I’ve asked myself the same question time and again. It’s identical with the wish to “see a village.” That quoted remark, of course, is an euphemism for seeing dirty bomas with mud huts and animal excrement. Fortunately, by the way, such villages are rare to find, anymore, at least along East Africa’s normal tourist circuit. What has replaced them are sedentary replications intended to make money from tourists.

Why do tourists pay to see them, even though they are clearly not authentic?

Even though outstanding African economic growth and potential is in fact a topic often found on the pages of the Wall Street Journal, I still hear from parents, “I want my children to see the way the other side lives.” Or “I think it’s important we see how fortunate we are.”

You don’t have to come to Africa to “see how the other side lives.” In some places like southwest Wisconsin near where I live, or the Ozarks or Appalachia, or the residual slums of our urban cities, real poverty and its resultant despair and destruction is no less than Kibera’s.

America’s “Kiberas” are not as widespread or large as Kenya’s, that’s true. But this is not a fortune of chance. It’s the result of a human civilization that wants to give everyone a modicum of happiness, that cherishes human rights.

That’s what America was mostly about, and it’s now what the world is mostly about. Kibera’s existence is our failing, just as Cabrini Green was and Appalachia still is.

Poverty is so complicated that it easily befuddles, and I think that’s part of the tourists’ desire to see Kibera or “a village.” They want to simplify the complicated. They don’t want to see poverty as something relative, but clearly defined and for sure, Kibera is.

But there is the same, absolutely identical misery, disease and angst in the unemployed, castaway homeless veteran on the streets of New York as any child walking the mud paths of Kibera.

Kibera, or the imagined dirty African village, or the homeless veteran need not exist. In a world where you and I assumed our basic human responsibility to our neighbor, there would be no Kibera.

So I believe the single-most important reason tourists want to “experience poverty” in Africa is to believe the same identical thing doesn’t exist at home. Or isn’t as bad. Or isn’t as extensive.

If one child is poor; if one veteran is homeless, it’s wrong.

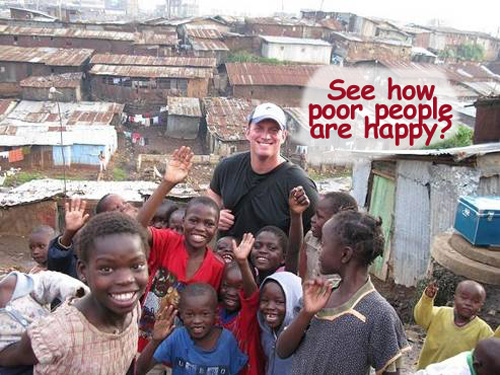

And finally — possibly even worse — the delusional tourist wants to find a smiling child who is dying, so that they can believe that poor is OK, that homeless can also be happy, that death smiles.

It’s OK to live in a multi-million dollar mansion and it’s OK to dab yourself with Chanel. But it’s not OK to live a world that allows Kiberas to exist. Kibera’s existence is our fault; the collective fault of an unjust world order. The children of Kibera can just as easily be the children of Trenton.

It’s not OK to go through life with the fantasy that Africa is besmirched and cursed and that Kiberas exist only in Nairobi and Shaker Heights exist only in Cleveland.

And it’s not OK to think that poor is OK, anywhere. There is no happiness in being poor or homeless, whether in Kibera or 49th Street.

Don’t come to Africa to validate your own fantasies.

That is disgusting. Bad enough that it exists….they should take the$30.00 and make a donation instead of gawking at those poor people

I have been through much of Africa on a motorcycle and have seen the poverty. I am not sure that all the help that the developed world has spent in Africa has helped the people. It seemed obvious to me that they need better governments and better education. Until the governments become less corrupt and the people are provided better education there will still be extreme poverty no matter how much charity is given to the poor.

I think it is a horrible idea — I am with you Jim

I find developing the poor as tourist sights astonishing and sad and distasteful. If people are so interested in poverty why not take a tour thru a slum or poor rural area in the U.S.

I think it a necessary reality check.

That is the height of depravity, gawking at people living in a slum. Unless you are part of an aid organization evaluating a settlement to assess its needs. “Happy” poor people indeed! Instead of paying $30 per visitor they should pay $30 to each family living in the place. This is just as insensitive as some people still believing that there were “happy” slaves once upon a time. Shame on them! The solution is to enable people to help themselves, whether that is in a developing country or on these shores.

Good grief, if slums turn you on, visit the places in your own city in which you’re afraid to drive! And then become proactive!

Agree with the comments above. It does depend on the situation.

One Christmas eve in Costa Rica my daughter and I were invited to leave our rural hotel and join the service at a small local church, dirt floor, barefoot kids. The Pastor read the Christmas story from the bible in Spanish. The kids came in singing “Da la mano a tu hermano” and laughing as they tried to teach us the words. We felt welcome. We were not prepared with gifts but my donation was considerably more than $30. My daughter was ten. She still talks about it.

On another occasion we were invited to bring gifts to an orphanage in Peru. We visited with books, candy etc. The girls performed a well rehearsed dance. They seemed to know the routine: perform for the tourists and you get your reward.

We were not comfortable. Next time we would just send the gifts.

Over the years my daughter and I have worked at soup kitchens and homeless shelters in our town. She has grown up knowing that poverty is real; the guests we meet are just like us and not a tourist attraction. Awareness of poverty is a good thing; insensitive gawking is not.

I spent 10 days in West Africa (Senegal, Guinea Bissau, and The Gambia) on an all inclusive tour. For me the trip was to simply set foot on a continent that had been in my thoughts for 60 years. The ruse I used was to see birds. One of the sponsors of the trip was Audubon. On two occasions we walked through local villages in the Bijagos Archipelago. As we sat sipping drinks on the fan tail of our small cruise ship, we discussed the life style of the villagers and talked about how their lives could be improved. We also looked at the view the villagers may have had of us, mostly wealthy foreigners. No conclusions were arrived at other than the proscription not to judge but rather to observe and be grateful for the opportunity to visit. We also visited small towns and villages outside of Bissau and in The Gambia and in southern Senegal. In one we were invited to an animistic purification ritual for a women who recently lost a child, or so the story went. All of the places visited had been visited by the same guides 4 to 8 times between mid January and mid March 2012. The guides and the tour group organizer had gotten to know many of the people we visited. A collection of gifts (soccer balls, pens, pencils, scissors, coloring books, crayons, small toys,) and I would guess, but never saw some cash. In the larger cities we drove through and on our many trips from dockside inland we passed through many places that demonstrated poverty by the standards of Dubuque, IA. Buying bananas from venders or the constant “For you, my friend, I will give you this for only $10, two for $12. Yes my friend I can give you this, I made it last night and it is now yours for only $6 . . .” reminded me of the tenuousness of life. I never felt that my purchase or lack of purchase would make a difference between life or death, but possibly between a the size of the next meal.

I am comfortable with a tour providing safe access to all types of environments provided the tours do not disrupt or do environmental or economic damage to those environments and that they provide as real and genuine an experience as possible.. It may seem that a tour is profiting from the misery of others, but when we visited the Fathala Wildlife Reserve Senegal there was a sense that the reserve itself was sustained by the fees paid. The animals were all but tamed and the roads were rutted and the game wardens knew exactly where the different “big game” animals were. It was a step up from a 1950 zoo. The animals were being exploited and we were given the feel of being on Safari. Unfortunately this may become the norm for all attempts to be among the animals of Africa as habitat loss, urban encroachment, and climate change take their toll on wild places.

It is interesting that you bring up Cabrini-Green are of Chicago. In the Fall of 1965 or 1966, I and seven other students traveled with a University of Minnesota sponsored tour of Cabrini-Green and adjacent areas to study the effects of gerrymandering of school districts and their effect on student performance. I was aquatinted with the poverty of Mille Lacs reservation and Red Lake reservation in Minnesota on trips there with my father, but didn’t come to understand and and see the connections of government created poverty until my visit to Chicago.From the safety of our van and under the “protection” of our guide I saw a poverty that I have never forgotten and which helped shape me ever since. We had the rare opportunity to be in a small church where Dr. Martin Luther King negotiated between an absentee landlord and the tenants. We got into schools and offices and saw the maps that sent white kids to one school and kids of color to a different school as the district boundaries went down an ally and circled selected houses. Was this a “trip into the slums”? Yes. Was it a life changing event for me? Let’s say it affected me and placed me much more firmly on the side of the underclass and gave me a stronger commitment never to complain about my lack of privilege and to never allow myself to enter into such a life of poverty.

I agree that we in the west have an obligation not to consume all the resources of the world, an obligation that we have not owned up to as of yet. That doesn’t mean we need to create a “western” society in all of the rest of the world. In Dakar it seemed that there was a decided effort for a small percentage of the population to emulate the American upper middle class. They were quite content to do it on the backs of the vast underclass. America was all to willing to help out as symbolized by the building of the largest U.S. embassy in all of Africa and placing it symbolically on the western most point of Africa.

Before I left for Africa, I read Africa’s Turn by Miguel and Easterly to get a small glimpse of economic hope for Africa. I also read The Slave Trade by James Walvin and T. C. Boyle’s Water Music and Graham Greene’s Journey Without Maps. Year’s ago I read his The Heart of the Matter: “If one knew, he wondered, the facts, would one have to feel pity for even the planets? If one reached what they called the heart of the matter?”

Perhaps Greene has it right; we come to Africa not knowing the facts and hence leave pity at home only to return to find that we are the ones to be pitied for not understanding the faults inherent in our imperialism.

Jim, I think that is horrible. I do not understand what people are thinking. Kris