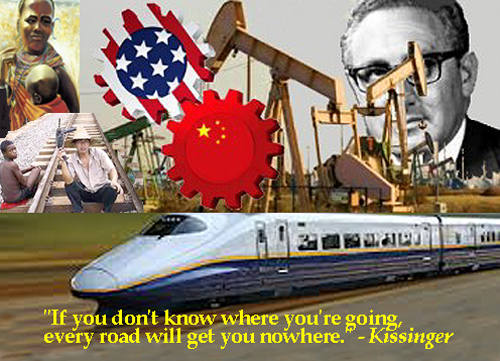

Rising conflicts between Chinese and Africans in Zambia and Malawi demonstrate that the Chinese do-anything desperation for Africa’s natural resources may be backfiring.

Rising conflicts between Chinese and Africans in Zambia and Malawi demonstrate that the Chinese do-anything desperation for Africa’s natural resources may be backfiring.

In 2009 China surpassed all other nations to become Africa’s leading trading partner. It is likely the continent’s biggest aid donor as well, although western institutions rating aid argue that the quid-pro-quo of Chinese aid moves it from the category of aid to investment.

I sat recently with three young Chinese men, probably still in their teens or early twenties, as we all waited for a delayed flight from Nairobi to Kampala. Our inability to communicate well was mitigated by the long delay. One of the fascinating things I learned from them was that they were not just excited about their upcoming work gig in Uganda, they were emigrating there!

They held one-way airline tickets from a Chinese construction company, jobs to build a highway in western Uganda, undoubtedly enough sudden cash that together they had just purchased a laptop in duty free, and … no intention to ever return home.

The rest was left to my speculation, but it seemed pretty clear to me that after their contract with the construction company ended, they would set down roots in Uganda and spend the rest of their lives there.

This is hardly new. It is exactly what the British did when they built the East African colony’s infrastructure in the mid 19th Century, except that they imported Indians rather than Scots. At the end of various construction projects, the Indians set down roots and today are as much Kenyan or Tanzanian as a Kikuyu.

The initial motives were identical as well. The British East African Trading Company was proudly a profit-making business which intended to extract as much as it could out of East Africa for the benefit of England. Chinese today are desperate for the natural resources necessary to power its society, lacking in China and flush in Africa.

Later Livingstone’s moral imperatives got entangled in British colonial development, but until that historical point the two capitalistic paths are identical.

What’s different, today, is that social authority derived of a growing embrace of self-determination, and the importance of human rights, are much different than two centuries ago. The British model of buying out local chiefs with bags of beads is quite similar to what the Economist calls “oil for infrastructure.” But the willingness of the local people to enter the deal is much more restrained.

Last week this restraint blew a threshold in Zambia and Malawi.

Mine workers staged a violent protest against their Chinese manager/owners. The Chinese have yet to mature beyond the desperation of need, and many are ruthless paymasters particularly when it comes to mining.

Last year Human Rights Watch documented increasing labor abuse by Chinese managing Zambia’s copper mines. Last week it came to a head when workers struck one mine and then battled security personnel and police, killing one of the principal Chinese managers.

In neighboring Malawi, what appears to be nothing less than a xenophobic vendetta against small Chinese business owners began last week. The government policy will essentially close down hundreds of small, local Chinese businesses in Malawi, developed I presume like the three guys I met waiting for the flight to Kampala want to eventually do in Uganda.

And in a stark 180-degree difference between the British colonial era, the Chinese ambassador to Malawi more or less endorsed the Malawian government’s move. There is little connection left between the homeland and the Chinaman who moved away.

In Dakar last week, Hillary Clinton remarked on these growing tensions and argued rather well that Chinese policy won’t work. “The days of having outsiders come and extract the wealth of Africa for themselves, leaving nothing or very little behind, should be over in the 21st century,” she said.

“Throughout my trip across Africa this week, I will be talking about what that means – about a model of sustainable partnership that adds value, rather than extracts it,” she added.

I’m not sure. I’m sure that Hillary’s admonition is correct, and that the right and moral way for a developed society to act toward a developing one is not the Chinese model. On the other hand, I’m not sure the American model is all that much better. Our “aid” to Africa is fickle, up with Democrats and way down with Republicans. All that Africa is left with is confusion and a certainty that American constancy doesn’t exist.

Africa needs infrastructure desperately. China needs oil desperately. There’s great constancy in that.