EWT is closed today but most businesses are open. Many African friends believe this is racism. Is it?

EWT is closed today but most businesses are open. Many African friends believe this is racism. Is it?

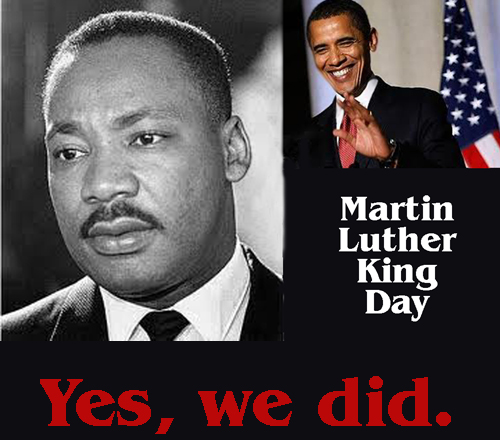

Martin Luther King Day is one of ten federal holidays, but in the United States it’s quite possible to have a near normal workday even on a federal holiday. The stock market, the post office and banks (which require a federal charter) are closed. But in many places — particularly in America’s south — life and work goes on nearly normal.

One of the most vocal opponents of gazetting the MLD holiday was Senator John McCain, the last Republican presidential candidate.

MLK Day is one of only two federal holidays celebrating acclaimed individuals. The other is Presidents Day. Neither holiday is observed as universally as the other eight federal holidays. Today about a third of American businesses that close on the weekends close on MLK Day, and about half on Presidents Day. So can we really claim that businesses which remain open today are racist?

Yes, of course. Particularly in today’s horribly politically charged environment. There can be no more telling confirmation of this than the behavior of anti-Obama forces, today. From the right comes the most vitriolic yet inane criticism of Obama ever sullied a sitting president. From my point of view, there is no other explanation. Obama is the catalyst.

I am a white man who has spent the majority of his life in black societies. I am witness to the change that King’s type of philosophy has made in Africa and at home.

What I most remember of King’s turbulent last days was unbelievable violence. My most vivid memory is as a very young journalist penned under a burning El Stop in downtown Chicago while the city raged in reaction to King’s assassination.

I remember gun fire was a regular sound in my low-rent apartment in Washington, D.C. during the summer of 1968. Or the unending sirens and tear gas around my apartment in Berkeley that fall.

King is duly revered for radically changing American society with non-violence. Yet what I remember most is fire, bullets and ambulances.

All of that was a long time ago, approaching a half century, two generations. Trauma has a way of finding its small berth among the many more ordinary memories of earlier life. My teenage years were lived in Jonesboro, Arkansas in America’s south.

Of the more than 1000 students in my public middle and high schools, there was not a single black. Less than a decade after I graduated I returned to Jonesboro for a wedding and learned that almost half the town was black.

I lived in Jonesboro for five years. I went to school, groomed pretty dogs at a vet’s, shopped on main street, sipped sodas at the donut shop, cheered at school sports matches, went to church socials. I remember regularly seeing only one black, Bessie Mae, our maid.

I left that society for the turbulent 60s, then left the turbulent 60s for Africa, and when I returned how things had changed!

King’s philosophy of non-violence, like Gandhi’s and to a much lesser but significant extent Mandela’s, were not eras of no violence. There was incredible violence, and this violence — as with the sizzling El Stop that nearly fell on me — will be blazoned in our memories forever. But with time we’re able to reflect that that violence was the reaction to those heros’ methodical, unswerving actions for a freer, fairer society.

Those movements as a whole were not violent. But the reactions to them were hideously violent, and then sometimes the frustration of the oppressed boiled over, and Chicago or Watts burned. But mostly it was not that. Mostly it was unarmed hundreds of thousands if millions of peaceful demonstrators being tear gassed and shot by police. It was violence in one direction most of the time.

And why? Because it was the desperation of those who knew they were going to fail. I really believe there is more good in the world than bad. Justice ultimately prevails. But the unjust will hang on for as long as they can.

I come from a deeply rooted Chicago family in the northern State of Illinois, the home of Abraham Lincoln. My father was sent from Chicago to Jonesboro, Arkansas, in the South to start a factory owned by an Illinois company to avoid the growing union movement in the North.

One of the first things my father did was pack up us three young kids in the car and drive us into the cotton fields west of Memphis. He stopped the car, said never a word, and made us watch for what seemed like an eternity black share-croppers toiling in the summer sun in a field owned by a white.

Try as I may, those faceless share-croppers and Bessie Mae are the only blacks I remember as a teenager even though I was part of a small minority, living in the midst of them.

Today, my President is black. My Attorney General is black. My closest friends — many in Africa – are black. My rare return to Jonesboro encountered many blacks. Memories created of life, today, are no longer monochrome or technicolor, they’re just wonderfully vivid.

Social justice does prevail. What King taught us is that nonviolence can achieve liberation and justice. But what he didn’t say was that nonviolence works only after provoking incredible violence against it.

Today, in America, ethnic, religious, political and racial tensions are seething. Economic stress brings out the worst in us. It would seem like there could be no harder time to stop work, but we must. We need time to stop, to reflect, to have a day of peace.

Happy Birthday, Martin! You’d have been 83, today!

I am spending MLK day volunteering at a community center, pulling weeds from a community garden, and helping repair the center. When MLK was killed, I went to work because my job was finding jobs for the mostly unskilled poor who were unemployed. I felt that was the best thing to do instead of sitting on my comfortable chair at home. Lots of Americans work in voluntary service projects on MLK day. One of the reasons to have a holiday, is so we can do something beneficial to others. However many people need to work today because they need the money. Some places give the day off, but no pay. There are racists in America but we are beginning to “overcome”.

Well said Jim. America continues to express growing pains as its people deal with inequality of opportunity. Racism is alive and well and a conversation most of America is uncomfortable having. And yet we managed to come together to vote President Obama into office and he broke that barrier. Women still have it to do. I appreciated your reminding all of us to make this a day of peace in our lives to honor Dr. King.

I am in the office today. Holidays are good for cleaning off your desk.

Tell your African friends that I actually met Dr. King once and shook his hand. It is an interesting story. Yesterday we observed the holiday at my church, where we sang, “We Shall Overcome.” I was moved to tears.