By Conor Godfrey

A friend of mine currently serving in Liberia recently related the following story about his friend Abdoulaye.

Abdoulaye’s store was robbed for several hundred US dollars.

After hearing the night watchman’s account and looking into the evidence, Abdoulaye concluded that the burglar had military training and was more than likely an ex-rebel from Liberia’s long and brutal civil war.

If anyone could recognize this, he could—being himself an ex-commander under Charles Taylor.

This story was related to me on the same day that I read about ex-combatants in the Congo who had been integrated into the Congolese military and were now extracting more from Congolese mines as soldiers than they ever were as rebels.

This is a real problem.

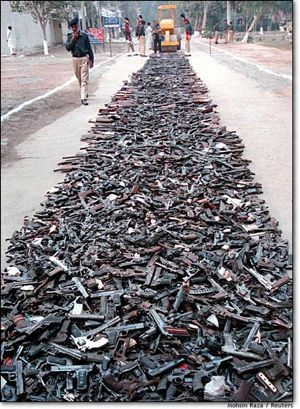

28 African States have been involved in at least one major conflict since 1980 and the continent is awash with former combatants.

Their resumes include weapons training, brutality, and a large network of similarly credentialed co-workers, but usually lack the skills to transition into civilian life.

Despite these challenges, so-called success stories abound.

USAID and other websites tout programs emphasizing job training, basic literacy and numeracy, psychological counseling, and a bevy of other seemingly logical steps to re-integrating militia members.

Even in Liberia, polling data suggests that the majority of ex-combatants feel accepted in their families and communities.

I believe that many of these programs do indeed help break the cycle of violence, but they are not a panacea.

Ex-Soldiers from Liberia and Sierra Leone were at the core of the group that massacred and raped demonstrators in Guinea last September.

Former combatants from other conflict countries now run criminal syndicates and extortion rings like those in the Congolese mines.

Policies surrounding re-integration send mixed signals.

The ICC spends millions of dollars attempting to convict officers at the same time that various truth and reconciliation committees try to make communities forgive and move forward.

These proceedings are further complicated by how national governments, local communities, and the international community view the combatants in question.

How politicized were the combatants?

How legitimate were their grievances?

Were they a legitimate resistance force like Umkhonto we Sizwe in South Africa?

Were they convicted of widespread atrocities like the Lord’s Resistance army?

Were they mild Islamists like the FLN in Algeria, or extremist members of Al-Qaeda?

Or maybe they were more like criminal gangs than armed forces.

Creative solutions exist.

In Saudi Arabia, Islamic radicals and their families are forced to attend classes taught by moderate Imams.

Next, they are given a dowry so that they might marry and become a stakeholder in a more moderate society.

In Liberia, the national commission in charge of disarmament and reintegration provided educational and vocational training to those willing to take it.

In Mozambique, combatants were paid a small stipend each month for 18 months so that they would not be a drain on their families or need to resort to crime.

In Sierra Leone, some former rebels were given motorcycles and licensed as moto-taxis.

Most countries employ a mix of vocational training and community based education programs designed to pave the way for former soldiers to come back home.

As conflicts in Sudan, the DRC, Nigeria, and elsewhere end (inshallah), regional and local actors need to have a plan in place to turn these traumatized young people into a productive force

General Macarthur said that “old soldiers never die they just fade away”–

There are worse things.

I agree. Well said. Very informative. Thank you.