Reset by the global recession, reconfigured by massive new production of oil and gas in the U.S. simultaneously with aggressive development of non-fossil fuels, Africa begins to collapse.

Reset by the global recession, reconfigured by massive new production of oil and gas in the U.S. simultaneously with aggressive development of non-fossil fuels, Africa begins to collapse.

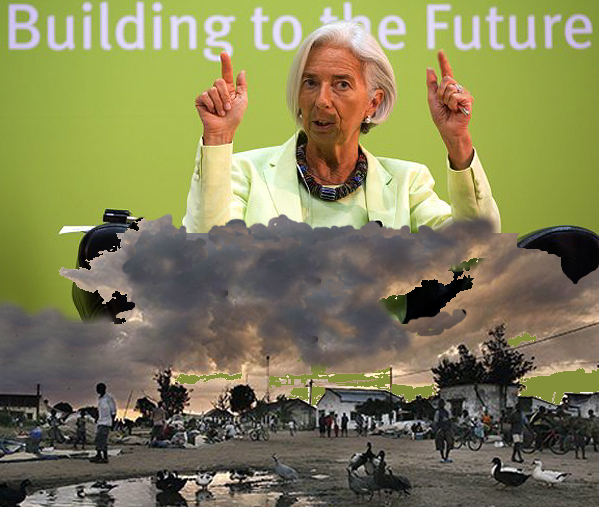

Nigeria, Angola, Egypt and Algeria, even Ghana and many countries not wholly dependent upon natural resources are in economic tailspins. The best example is Mozambique.

The IMF suspended emergency relief payments to Mozambique in April. At the time it was more a political than economic move, retribution for the country’s failure to report nearly $1 billion in hidden liabilities.

But that has turned into an unending and apparently impossible negotiation with a government that manages to hide billions from scrupulous international bankers. Topping its list of mischief is an $800 million bribe that Brazilians admitted to American investigators last week they paid the country’s national airline.

Allegedly malfeasance not corruption lost billions more on a lavish presidential palace, questionable bridge, unfinished and poorly designed airport, and more than $2 billion in cash to settle a generations’ long war with the Frelimo rebels.

Today inflation is at 30%. Bond yields are hilariously high and the local currency has lost about half its value.

Mozambique is without doubt the most severe example. But why do I say the “best” example?

Many argue that Mozambique’s plight is one of corruption, not the result of any other economic dynamic. They’re wrong.

Corruption is a two-way street. The massive bribe to LAM, the country’s airline, came from the Brazilian manufacturer of LAM’s planes. One can only suppose that Embraer saw no other way to stay afloat in Mozambique. There are few countries in the world that speak Portuguese besides Portugal: Brazil and Mozambique are two. There’s no miscommunication here.

The alleged misallocation of so much cash to Frelimo rebels is also more complicated than it seems. War is expensive. Rebels thrive in declining economies. Few wars on the African continent have been so long and so destructive as the civil wars of Mozambique.

It would take a Ph.D. thesis to prove me correct, but I’m confident it would: Mozambique’s misery is because the world no longer craves its once valuable natural resources (oil and aluminum). When the world did, the country made a staggering climb from a GDP of $4 billion in 1993 to $34 billion in 2014, and it ended a war many said would never end.

Lower the price of oil and depress even more the price of aluminum and you’ve wrung every drip of innovation from the land. Add a pinch of climate change for total disaster.

Unlike Nigeria, more like Angola, Mozambique wasn’t peaceful enough to develop secondary industries. It was dependent exclusively on its natural resources. Cynics cheerfully claim that the wars that caused this situation were further proof of political ineptitude, but that takes another Ph.D. thesis: the wars in Africa were a result of western exploitation of the continent’s natural resources; more simply, global economics.

Now I realize it’s asking you a lot to accept my two Ph.D. theses. But suspend your skepticism for a moment and you’ll understand that the continent’s imminent economic collapse is not a fanciful notion.

With the exception of some North African countries, Nigeria and South Africa, the continent has nothing to sell but natural resources. And those exceptions depend organically on all their neighbors, mostly on trade, but also for financial growth as they capitalize their poorer cousins.

One politically biased but respected Mozambique analyst called it the “collapse of the house of cards.” I agree, but he’s wrong as to why. The cause is not simply bad African leaders and corruption.

It’s the system, stupid, the system.