EWT currently has one safari operating in Kenya and I will be leaving on the weekend to take another to Tanzania. These are the first safaris EWT has operated since the pandemic and we’re learning a lot about what travelers like me should expect and how radically different the business landscape has become.

EWT currently has one safari operating in Kenya and I will be leaving on the weekend to take another to Tanzania. These are the first safaris EWT has operated since the pandemic and we’re learning a lot about what travelers like me should expect and how radically different the business landscape has become.

There’s a lot for me to still learn but I have some very preliminary advice to persons considering traveling to East Africa. It boils down to money: Don’t go if you don’t spend a lot but don’t spend a lot without being very, very careful.

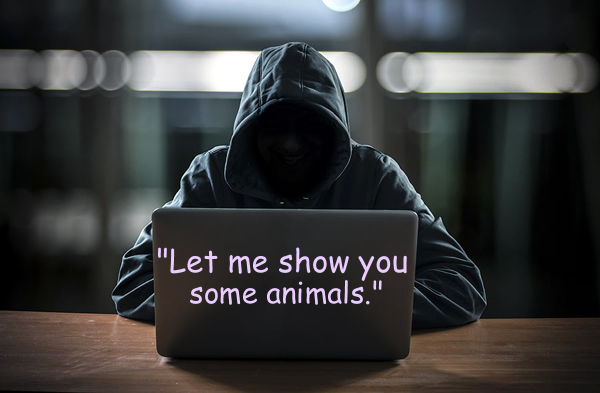

Travelers are already getting wildly scammed by locals sweeping up the debris from the pandemic. Down-market companies are nonexistent. Midmarket companies are failing or flailing. Only some of the established upmarket companies seem well and alive.

I recently got a report of someone who just returned from Tanzania. She wanted me to know that Ngorongoro Crater wasn’t really worth visiting.

When I looked into her itinerary it turned out that she hadn’t been within 25 miles of Ngorongoro Crater. She was taken to the “Empakaai” crater by a guide who told her that it was Ngorongoro. She’s right. Empakaai might be wonderful but it can’t begin to compare with the august splendor of Ngorongoro Crater.

That “guide” who she extolled as being so good and so cheap either didn’t have to pay the high fees to visit Ngorongoro or he pocketed them.

But more importantly she was denied what most travelers argue is the single most beautiful sight in all of East Africa.

Don’t think I believe that the rich companies are more moral. But they do play capitalism much better. During the pandemic they bent contracts, overlooked previous obligations and as we began to emerge, offered preferential discounts and remained prompt and courteous through it all.

They could afford to. They were rich. It was similar with many international airlines. Huge loses were born by travelers on RyanAir and Swiss, for example, while highly capitalized carriers quickly came up with postponing and voucher packages, sometimes even out and out refunds.

Of course keep in mind that the highly capitalized carriers were so in large part because of the largess of the American and European treasuries. There’s no counterpart for them in the East African tourism business.

The last time an EWT safari was in sub-Saharan Africa before our first Kenyan return several weeks ago was on February 22, 2020. That was 21 months ago. That interval was more or less the same from the beginning to the end of the great flu pandemic of the last century, so I looked at that history for some guidance as to what might happen, now.

The clear conclusion is that African tourism will take years to recover, and that the newer areas – like Tanzania – will take much longer to stabilize and recover than the more mature areas like Kenya and of course, South Africa.

We’re only getting hints right now of what this means and I hope my near month-long journey soon will clear some of the fog. But for the time being history suggests that the inflexibility of newer ventures is their nemesis, and the flexibility of mature business is their saving.

The most mature safari business that exists has a history that extends back before the first flu epidemic. It was then rich people traveling with giant caravans almost exclusively to hunt. Teddy Roosevelt and the likes.

What was lost in the 1918 pandemic from the new African tourism industry that actually began at the turn of the 20th Century were fresh, new, non-hunting “guides” who invited people like T.J. Simpson from Trenton, New Jersey, to bring his Model-T Ford with him on the boat to save transport costs once he got there.

Horses were very few and unreliable in tse-tse country, and the “British four-wheeled petrol-engined motor car” which made its debut in Mombasa in 1895 was extremely expensive, used mostly for diplomats and royalty. Like Teddy Roosevelt and the likes.

So Mr. Simpson (can’t find his first name) drove his Model-T onto the boat in New York and set out on his journey to Liverpool then down to Cape Town then up to Mombasa before the pandemic had fully ended.

He traveled all over East Africa on a dime with a non-hunting guide in 1921. I’ve not found a single subsequent Mr. Simpson. The new industry collapsed with his legend.

I expect that’s what will happen to the mid- and down-market in Tanzania, today. To a lesser extent in Kenya and perhaps hardly noticeable in South Africa. As we gear safaris back up we’re having a dickens of a time working with the mid-market companies and the down-market companies have shuttered their windows.

Apparently British settlers returning to Mombasa as veterans from WWI brought the flu into Kenya in late 1919/early 1920. It devastated the coast wiping out 4-6% of the population in a few months.

But what’s really important is that the aftermath continued for years. Shortages with farm labor sent Kenya into a recession, crippling an industry that was just beginning to get a toe-hold with regional exports and to India.

The health care section of the society – admittedly reserved at the time for the colonials – came to a standstill. By 1921 you would be hard pressed to find a hospital open. According to one report most of the nurses had died.

Tourism seemed to prosper in history with the lavish accounts of Mr. Simpson. But I think the reality that he was a loner is more cogent. There’s little news about Kenyan tourism for another fifteen years.

The flu is not Delta. Times are so different. The “business” of safari, the speed at which companies fail, recover or are replaced is certainly much greater.

But for the time being, ‘sibili kidogo.