Most younger nations in the world celebrate several independence days: the transfer of power (“Jamhuri Day” in Kenya) and the day self-rule began (“Madaraka Day”). South Africa’s “Freedom Day” marks the transition from post-apartheid rule. The variety of celebrations reflects the complexity of achieving and implementing self-governance.

We don’t like complexity in America, particularly during these Information Wars. Like the old man I am, the simpler my day looks, the better! We celebrate only one day to mark the end of British colonialism, July 4th, the date our bold Declaration of Independence was signed.

Yet America’s transition to self-governance is woefully incomplete compared to younger nations: Voting in many American states is far more difficult than voting in Kenya or South Africa.

Our constitution lacks the clarity of “equality” that either Kenya or South Africa or a myriad of other younger nations give their women, or for that matter, foreign languages. We have yet to fully redress the sufferings of the indigenous peoples that our “self-governing” classes displaced. In many respects we’ve shackled them further.

Where we excel all other cultures in my opinion is individualism, the linchpin of entrepreneurism, the reason we revere “small business” and the intractable safeguard of our federal system that allocates power among the states not by the numbers of people who live there.

The idea is that each state is so unique that regardless of its actual population size it must be protected from threatening forces from without.

Wyoming has a population of 577,000. California’s population is 39½ million, but each state is allocated only two senators. Every Wyoming citizen has about 70 times more power in the U.S. Senate than a California citizen.

Theoretically this inequality is balanced by The House, where California has 53 representatives and Wyoming only 1. But wait. I won’t do the algebra but in the end one-seventieth is smaller than one-fifty-third.

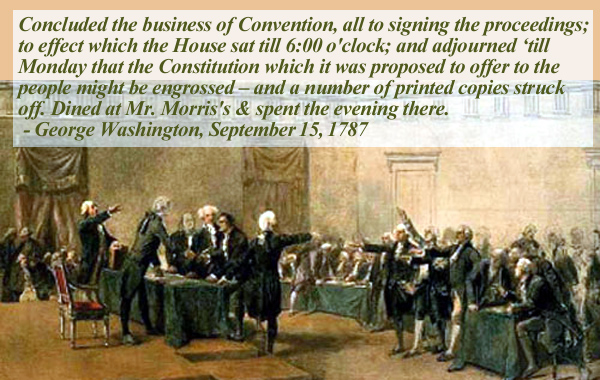

I try sometimes to imagine myself at the Constitutional Convention which followed the Declaration of Independence, not necessarily as a participant but just as an observer. It took 11 years after the July 4th Declaration to finally produce a self-governing document.

But on September 15, 1787, in that terribly small wooden room still stuffy and hot from a lingering Philadelphia summer, a treatise of self-government was passed by 39 of 55 mostly aristocratic farmers and businessmen.

It must have been one of those moments in the lives of everyone there that seemed to have been revealed rather than created. There had been so much rancor and deceptive maneuvering that it was a surprise to most that the process actually ended.

For those weary and sleepless and itching in their britches I imagine the first moment after that final vote was one of enormous relief and the worry that the lust for relief hurried the ending.

Then in the unusual silence that follows every end, there must have been a floating sense of wondrous surprise at what had just been accomplished. No king but a kingdom nonetheless.

And as each delegate lumbered away through the hot evening, they must have been overcome with a lasting fear of failure. Nobody got even most of what they wanted. Slave owners and freemen, farmers who fed the bankers who underwrote their seed, prelates who comforted revolutionaries, militia men with the new governors who now controlled them… Nobody could be everybody.

It seemed in the end that more had been given away than secured. Is failure won? Thirty-nine of 55 delegates voted to finally conclude the procedures. Two days later during the actual signing, only 42 were still around. Thirteen who had voted “No” had left.

The fear of failure was the most lasting of all those emotions that followed the Constitutional Convention. The “ratification” of the September 15th vote, with the 39 “Yes” delegates signing their name onto the September 17th Constitution provoked no celebration. Everyone just dispersed, exhausted by the heat and work, breathless with opportunity, shackled by the fear of failure and disunity.

Americans never shed their fear of failure and disunity. The brand left on our 1787 first document governed everything that followed. Fear of losing our free will, our individualism.

We are incontrovertibly today losing our individualism. The world grows too full and the planet’s resources face the terrifying prospect of being too little. But still we balk at reimagining ourselves part of a group as the way to do something about our predicaments. Just like the 13 sour-grapes delegates who absconded before the signing of the Constitution.

Instead we Americans are sure that we alone, individually, cowboys on the high butte with our assault weapon strapped into our stallion’s side saddle can survive any apocalypse except the one where we cash in frequent flyer points to get through Saint Peter’s gate.

The certainty that no one knows better than us with the fear that we’ll fail.