Many Americans don’t care if something’s going extinct: it’s just “the way it is.” So it’s no surprise that big game poaching is as much an American problem as it is an African one.

Many Americans don’t care if something’s going extinct: it’s just “the way it is.” So it’s no surprise that big game poaching is as much an American problem as it is an African one.

“Put bluntly,” writes Australian ecologist Euan Ritchie, current species extinction is an ecological “avalanche” with current rates 1000 to 10,000 times higher than would be normal in a balanced environment.

Most people realize that the extinction of one species has the potential to threaten a whole ecosystem. We might not fully understand, for example, why that little flower in the Amazon jungle keep the canopy from falling down, but most people in the world accept that it might.

But rhino? What purpose, exactly, does this beast have? We know an awful lot about rhino, and nothing suggests it’s integral to the status quo of any particular environment. In fact, it rarely exists in the wild, anymore.

The answers are allusive and often personal. There are probably fewer Americans as a percentage who believe extinction of something like the rhino is a priority than compared to other societies, but likely and fortunately still probably a majority.

Americans were the ones to formalize the concept of an endangered species with historic legislation in 1973. And shortly after the Endangered Species Act was enacted, the sale of rhino horn was banned.

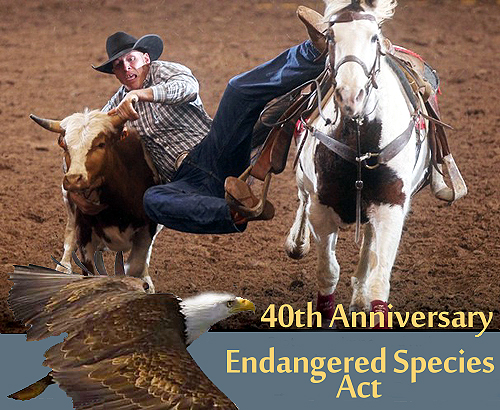

Almost forty years later, Jarrod Wade Steffen, a poor kid from McHenry Illinois, just wanted to get his mom some money after his rodeo career collapsed, so he started trafficking rhino horn.

There’s more to it, of course, including Mom sneaking out of California with a suitcase of small bills totaling more than $100,000. And there’s a lot we still don’t know, since Wade’s plea agreement with the Justice Department suggests he’s still involved with helping ongoing investigations.

At 21 years old, Wade was struggling to make a living competing in rodeos. He’d won his events in Texas, Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, Oklahoma, Minnesota and Missouri and while he certainly wasn’t a star to watch his trajectory was OK.

Then he got injured in the eye by a camel he was trying to train. He started driving a truck, which earned a better living anyway than rodeos, and moved to Hico, Texas.

There in Texas, that wild and rowdy and never wholly moral place, Wade reconnected with old rodeo acquaintances who had rhino horn for sale. Most of them had it legally, usually from old big game trophies shot before the 1976 ban from the Endangered Species Act.

It wasn’t hard to find someone to sell to. Thirty-three times between June of 2010 and just before he was arrested in February of 2012 Wade sent rhino horn to Vinh “Jimmy” Choung Kha in Orange County California and earned hundreds of thousand dollars.

In that 18-month period, the American cowboy, Wade Steffen, trafficked in more rhino than were poached in Kenya.

Kha in turn sold the horn to Zhao Feng, a Chinese national living mysteriously in Orange County, part of the new rich Chinese buying expensive California real estate and not really doing much else. Kha laundered the money he got from Feng through his import/export business and his girlfriend’s nail salon.

The ring was blown apart when Wade, his mother and his girlfriend, were stopped at the Orange County airport with three suitcases carrying around $300,000 in cash.

Wade, his mother, his girlfriend, Kha, Feng and a bunch of others, including an antique dealer in New York, were all subsequently arrested. Federal authorities called it the biggest bust in the history of illegal rhino horn trading.

“These individuals were interested in one thing and one thing only – making money,” said Fish & Wildlife Director Dan Ashe.

Whether that’s wholly true or not, one thing is certainly wholly true:

Wade, his relatives and friends, and all the other people around who knew what he was doing don’t care if something goes extinct.

Extinction, and in particular rhino extinction, is not just an African problem.