Less than three short years from the Arab Spring, ethnic domination and conflict is growing throughout Africa. Capitalism may be the culprit.

Less than three short years from the Arab Spring, ethnic domination and conflict is growing throughout Africa. Capitalism may be the culprit.

I once felt that education alone could ameliorate racism, but as demonstrated especially in places like Syria, Egypt and Rwanda, that’s not proving true. At least not when that education has occurred over fewer than several generations.

Few countries in Africa have been beset by ethnic turbulence to the extent of Rwanda, and fewer still have enjoyed such rapid prosperity in my life time. The guilt that America and France felt for having allowed the 1994 genocide was followed by such enormous amounts of aid that almost all the country, today, looks very similar to a successful western society.

Unlike the rural areas where my mother lives in Wisconsin, similar rural areas in Rwanda have fiber optic cable and access to high speed internet. The system of roads now rivals both in extent and quality that of places in rural Europe.

While the number of actual doctors is relatively low in Rwanda, the level of health service is high for an African country, as heady social services planners recognize that most of the diseases prevalent in Africa are best handled by nurses and health clinics rather than hospitals.

So as Rwanda’s ostensible peace and prosperity grows, many of its African neighbors find it increasingly difficult to plan policy based on Rwanda’s past of ethnic turbulence. South Africa announced recently, for example, that Rwandans who were given exile in the 1990s must now return.

Even the richest of African countries like South Africa feels a conflict when its national resources are used by foreign nationals. But the Rwandan exiles in South Africa are terrified of the prospect of returning home.

I am the child of second generation immigrants who spent their lives inside their own ethnic communities, and while my parents’ generation intermarried, usually one or the other parent infused us children with a certain ethnic identity. I think this is true for much of America.

And now, as a fourth generation of melded cultures, my childrens’ generation seems truly ethnic free. So it is reasonable to wonder if that’s the magic number: four generations of ethnic melding to emerge from racism.

Yet Rwanda stands as the example this is not true. The Hutus and Tutsis have intermarried for so many generations over hundreds of years, that their language has become the same. But there is arguably no ethnicity in the world that remains as hateful and separating.

The Alewites and Christians of Syria have been the persecuted for centuries, until somehow the Alewites imposed control on a region where albeit they remain a minority, they are free of their persecution. Conflict as open battle was reduced in Syria, but at the cost of many freedoms like speech and political opposition.

Compared to Rwanda, the South African ethnic problems remain in infancy, even though they were forged more than two centuries ago and reenforced throughout the modern era. Then, presto in 1993, a political system emerged that based upon its constitution remains one of the most just and fair on earth.

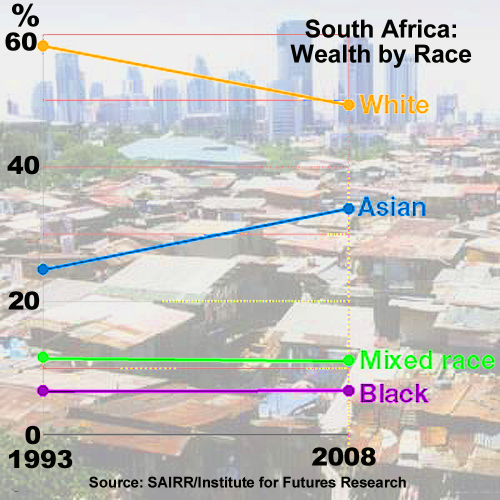

But a generation has nearly passed since then, and basic economic inequity has not improved for the majority. There has been interesting change: the two groups of South Africans that have always held most of the financial worth, the whites and the Asians, seem to be trading places.

But the vast majority of South Africans remain stalled out at the bottom. Now it’s important to add that the overall level of all sublevels has improved. There is more wealth all around, but the relationship of the ethnic groups at the bottom hasn’t changed to those at the top, even though it is the bottom group which holds political power.

It seems to me that there is something world-wide that ensures a status quo of racism defined by ethnic domination of politics and/or economies. And South Africa is the place to study this mystery, because this is precisely where the lowest economic classes hold the most political power.

And lo and behold, similarly in America, the middle class holds political power, yet it is mired in stagnation. In America, today, economic classes are acting as if they are ethnic groups.

And in both South Africa and America, political power has not ensured economic progress.

Africa is growing rapidly in economic terms… as its ethnic travails increase. America’s ethnic travails are diminishing, but it’s economic stratification grows stronger and more inequitable.

Is this, then, the universal relation? Capitalism is racism?