The withdrawal from CITES (Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species) by part of the world where half the elephants live would throw the treaty into turmoil, even though that might not immediately threaten elephants.

I find myself slowly moving into the southern African camp after a life-time of supporting the East Africans. I have little doubt that relaxing the ban on ivory sales will increase poaching, and that will unequivocally negatively impact tourism in East Africa.

But I’ve seen more and more the destruction that elephants are doing, and the pitiful response of NGOs and governments alike to assist with the human sacrifice. More and more, CITES is looking like a Rich Man’s Treaty.

Yes, CITES protects Kenyan tourism. But what does that mean? Is it protecting revenue to develop the country and sustain its environment, or is it more just giving us rich westerners a better vacation?

The withdrawal from CITES was proposed by Botswana. The 15 nations in the trading and tourism organization Botswana is petitioning would be directed to urge their governments to take official action to withdraw, which will take a long time. But if that ultimately happened, CITES would be thrown into turmoil.

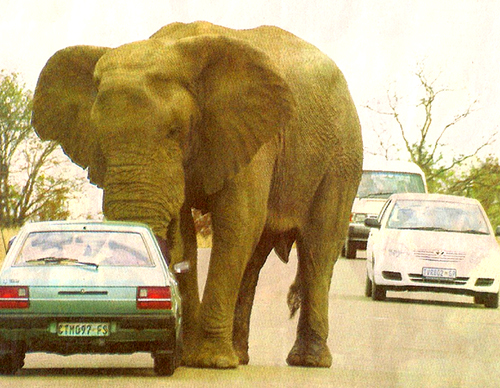

I doubt anything except hot air will come out of the convocation, but it makes us realize once again that just protecting elephant without protecting people begs fairness. Elephant protectors argue that the healthier environment and proper management of these jumbo forms of wildlife actually contributes to economic stability. Politicians, farmers and the poor feel significantly otherwise.

With as much coincidence and political adroitness as the Goldman Sachs hearing before a successful Democratic vote to move forward bank regulation in the U.S. Congress, Botswana and Zambian media last week were incessant in reporting about a family of elephant near Sesheke destroying crops and threatening farmers and villagers.

Sesheke is in the triangular border of Namibia, Botswana and Zambia just outside the famous Chobe National Park, which earns more tourism revenue for Botswana than any of its other protected wildernesses. Botswana argues that the human suffering in the area is simply not worth the tourism revenue, or that the tourism revenue won’t suffer that much if elephants are protected less, or both.

Botswana claims that it could earn up to $7 million annually by selling ivory that was simply harvested from naturally dead animals if it withdraws from CITES. Meanwhile, it spends $1 million annually just to manage the stockpile of collected ivory it can’t sell. These are significant amounts for a poor country.

But alas, the southern Africans aren’t doing their cause much justice this time around. The whole meeting grew farcical yesterday when it elected the Zimbabwean Ministry for Tourism its chairman. There hasn’t been any significant tourism in Zimbabwe for years, and nearly everything Zimbabwe does these days destroys tourism and its own development!

So the serious intellectual argument dissolves in farce. My wrenched little conscience starts laughing hysterically.

Ultimately, I just feel that the Africans have the preeminent position in determining not just the morality but the economy of this contentious debate, and I’m ready to give them the benefit of the doubt.

But if they make their spokesman and point man someone from a country with as destitute morality and economy as Zimbabwe, how on earth can I embrace their arguments?